An article about “remakes” of independent documentaries, from the November 20, 1998 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

Shulie

Rating *** A must see

Directed by Elisabeth Subrin

With Kim Soss, Larry Steger, Rick Marshall, Eigo Komei, E.W. Ross, Marion Mryczka, Ed Rankus, Kerry Ufelmann, and Jennifer Reeder.

What is it about American culture that compels the film industry to do remakes? The compulsion has been growing over the past two decades — one of my oldest friends, a cinephile and sometime screenwriter based in Hollywood, was already viewing it with philosophical resignation ten years ago. As she put it, “My best friends and I have been spending most of the 80s sitting in cars discussing remakes.”

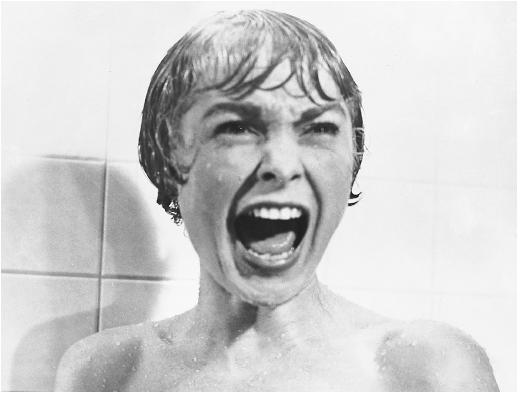

Since the early 80s we’ve been inundated with more cultural objects than ever before, but we have less and less sense of what to do with them. It’s easy to explain the Hollywood remake syndrome as unimaginative cost accounting: it made money before, so why not do it again? Then there’s the expanding youth market, which encourages unimaginative cost accountants to figure that former hits can be recycled for younger generations — one of the justifications offered by Gus Van Sant for his forthcoming remake of Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho. Read more