From The Soho News (June 4, 1980). In the interests of full disclosure, I should note that Jackie Raynal was and is one of my dearest friends. — J.R.

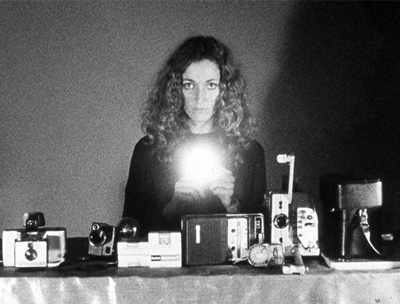

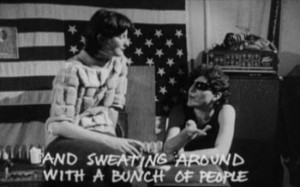

Deux Fois

A Film by Jackie Raynal

Bleecker Street Cinema, June 9

Debt Begins at Twenty

A Film by Stephanie Beroes

Millennium, May 24

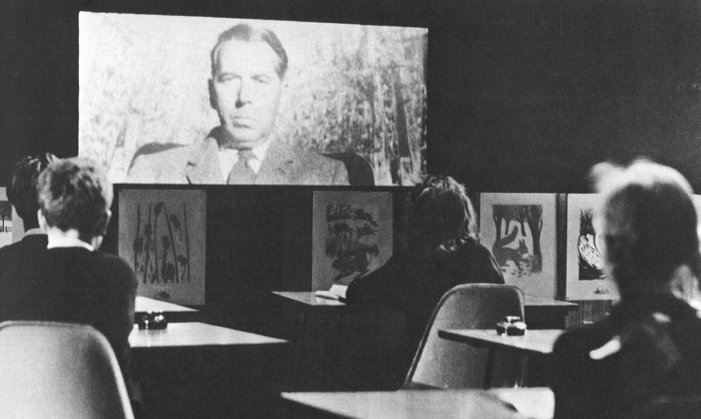

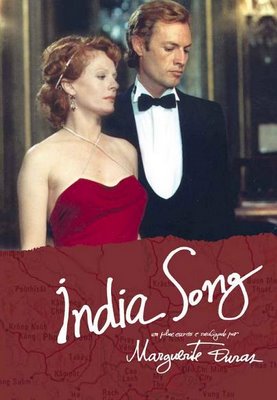

Recalling my four successive visits to the Cannes Film Festival in the early ’70s — when the daily glut of movies and accompanying hardsell was already enough to turn a hardened film freak into a deflated beachball — I still harbor fond memories of the kind of movies that used to spend my days looking for, and the ones that would savor for days more, days on end, once I found them. They were movies that allowed me and Cannes to slow down and linger a bit and regain our strength, and afforded us that pleasure by refusing to hype us into or out of anything that denied either of us the solipsistic joy of total self-absorption.

By taking their own sweet time (all the time in the world) to explore their own bittersweet fantasies, and allowing us to follow them only if we insisted, these movies were like little self-contained oases conjured up and plunked down improbably in the midst of camel stampedes, which is probably why so many of my colleagues hated them — and why most of you, in turn, have heard of so few of them, if any at all. Read more