From the September 15, 1995 issue of Chicago Reader. —J.R.

Films by Marguerite Duras

It’s surely indicative of the scarcity of Marguerite Duras movies that even a dedicated fan like me has managed to see only seven of them — and for one of those I had to drive 100 miles, from Santa Barbara to Los Angeles. No Duras film has been distributed in the United States for years, and in preparing this article I wasn’t even able to obtain a complete filmography; my own provisional list includes 20 titles, stretching from La musica in 1966 to Les enfants in 1982.

If one extends this list by adding adaptations (by herself and others) of Duras literary works, the scripts she wrote for other directors, and two films by Benoit Jacquot revolving around Duras, the figure is 31 films, most of them features. So it’s no small achievement that Facets Multimedia (which, thanks to the efforts of Charles Coleman, has recently featured such adventurous fare as Manoel de Oliveira’s Valley of Abraham and an exhaustive Nanni Moretti retrospective) will be showing a dozen films from this list over the next couple of weeks, most of them in brand-new prints and most of them four to six times. I’ve seen the five features in the series that were written and directed by Duras and the two written by her and directed by others; Facets will also screen three adaptations and the two Jacquot films. Though I regret many of the missing titles, the two missing Duras-directed items that I’ve seen are relatively expendable. La musica, codirected by Paul Seban, is so conventional compared with her other films that it looks more like an adaptation than her own work. And the 1976 Son nom de Venise dans Calcutta desert (“Her Venetian Name in Calcutta Desert”) — which combines the prodigious sound track of her India Song with soporific camera moves around an abandoned, decaying house — has got to be one of the most boring movies ever made, a false “good idea” if there ever was one.

Of course, there are plenty of critics who will assure you that all of Duras’ movies are boring. The on-screen action in those I’ve seen tends to be both minimal and as slow as molasses, but that certainly doesn’t add up to boredom for me in such films as Nathalie Granger, India Song, and Le camion (“The Truck”). There’s plenty going on in these movies at every moment –in their sound tracks more than in their images, but above all in the interplay between sound and image. In Agatha, ou Les lectures illimitées (1981) and Les enfants [see below], where there seems to be less going on, boredom is a more plausible reaction, but even in those films I find myself more gainfully occupied than I am at most narrative movies.

Duras’ narcissism — she often speaks her own texts during the films — has been held against her, yet it seems to be every bit as germane to her art as the purely physical narcissism of John Wayne, Cary Grant, and Toshiro Mifune. This narcissism is evident whenever one hears her reciting her own prose, which happens in at least four of the Duras-directed features showing at Facets. (It’s been too long since I’ve seen Les enfants for me to recall if she speaks in that film, but her voice can be clearly heard at the other end of a telephone in Nathalie Granger, offscreen in India Song and Agatha, and triumphantly on-screen and off in Le camion.) When I met this short, formidable woman about 15 years ago in New York, what impressed me most her was her Brahman-like relaxation and pleasure in her own strength and authority, partially expressed in the warmth and economy of her phrases. The fact that she’s attracted a mass audience with some of her fiction (most famously The Lover, the only one of her novels I’ve read) and persuaded many of the best actors in France (including Gerard Dépardieu, Daniel Gélin, Michel Lonsdale, Jeanne Moreau, Delphine Seyrig, and Bulle Ogier) to star in her marginal independent movies must be galling to some of her avant-garde competitors. Some people even peevishly try to use her commercial success to discredit her Marxism. Of course women as sure of themselves as Duras are bound to be viewed with suspicion and perceived as troublemakers.

Duras, who turned 81 last April, was born near Saigon in what was then French Indochina and is now Vietnam and remained there until she was 18. Though prolific as both a writer and a filmmaker, she didn’t publish her first novel until she was 29, and she didn’t start working in film until she was in her mid-40s, when she wrote Hiroshima, mon amour for Alain Resnais; her first solo feature as a director, Destroy, She Said (1969), was made when she was 55. So it shouldn’t be surprising that memory plays a central role in her work. Her political past includes work in the Resistance and membership in the French communist party; a central facet of her work is its embrace of leftism, which is no less consequential than her preoccupation with form.

“Faulkner plus Stravinsky” was Jean-Luc Godard’s description of Hiroshima, mon amour shortly after it shook the film world in 1959, forming the first real cornerstone of the French New Wave. One could interpret in numerous ways what he meant by Stravinsky — the clashing juxtapositions of a contemporary interracial love story set in Hiroshima, the powerful atonal score by Giovanni Fusco, the jagged yet musical editing. But when it comes to Faulkner, it’s pretty evident that Godard was thinking of the coexistence of past and present. The film’s French heroine — an actress making a pacifist propaganda film in Hiroshima — tells her lover, a Japanese architect, the story of her traumatic affair during the war with one of the German soldiers occupying France. He was killed, and she was persecuted by her neighbors because of the affair. What was most innovative about Resnais’ first feature was its rejection of flashback conventions: when the twitching hand of the sleeping architect reminds the heroine of her German lover’s dying convulsions, Resnais cuts immediately from the former to the latter, without the warning of a fade-out or dissolve accompanied by a musical cue — demonstrating how the past can be as immediate as the present in the heroine’s consciousness.

It’s worth adding that Duras’ writing is as distinctive as Faulkner’s: her musically shaped dialogues, composed of short sentences, are as recognizable as his rhetorical monologues composed of long sentences. In their formal experiments, both writers tend to circulate compulsively around the same themes, emotions, characters, and settings, as if trying to express an obsessive romantic content unreachable by more conventional means — a content derived from tribal transgressions, from incestuous and interracial love. In fact the experimental “new novel” that took root in France after the war, a movement Duras has always been identified with, was arguably less “purely” formal and more an effort to confront the emotional traumas and moral crises produced by French colonialism and the German occupation of France. Various sexual taboos often overlapped with these historical facts: Duras has often discussed her emotional intimacy with her two brothers in Indochina in terms of incest, and Agatha directly addresses incestuous desire between a brother and sister.

No doubt this is an oversimplification of a complex and far-ranging literary movement. But if one considers the colonial background and sexual obsessions of Alain Robbe-Grillet (the “new novelist” who scripted Resnais’ second New Wave feature, Last Year at Marienbad) and the importance of the German occupation to Jean Cayrol (the new novelist who scripted Resnais’ third feature, Muriel, as well as a short about the concentration camps, Night and Fog), this supposedly formalist movement begins to take on a certain ideological shape. The hero and narrator of Cayrol’s novel Foreign Bodies, for example, is both a compulsive liar and a former Nazi collaborator, so the periodic deconstruction of the narrative that occurs whenever he exposes his own lies to the reader might be said to correspond to the moral and spiritual deterioration of French citizens during the Occupation.

To my mind Hiroshima, mon amour — Duras’ first work in film — is the greatest film she’s been associated with. But because of its relative familiarity Facets is giving it only two afternoon screenings this weekend. (It’s giving the same treatment next weekend to Jean-Jacques Annaud’s 1992 adaptation of Duras’ The Lover, her autobiographical novel about a teenager who has an affair with a Chinese businessman in Vietnam. I haven’t seen this film, but Duras devoted an entire book, The North China Lover, to repudiating it; I’m only guessing, but I suspect this is the worst film she’s been associated with, though it’s almost certainly the most familiar to contemporary audiences.) You shouldn’t pass up Hiroshima, mon amour, however — especially if you want to see Such a Long Absence (1961), for which Duras also wrote the script.

Such a Long Absence is coscripted by Gerard Jalot and directed by Henri Colpi, an obscure figure who edited Resnais’ first two features and wrote an interesting and comprehensive early study of film music. Its main source of interest today is the dialectic it forms with Hiroshima, mon amour. Both films are structured around an extended dialogue between a couple that might be called psychoanalytical — one partner attempts to dredge up the other’s repressed, painful memory of the war. In Hiroshima it’s the man who assumes the psychoanalyst’s role, and he succeeds. But in Colpi’s melancholy feature — set in a dingy Paris suburb and attractively filmed in black-and-white ‘Scope — it’s the woman, and her effort basically fails.

Played by Alida Valli, the woman in Such a Long Absence runs a working-class bar and is still grieving the loss of her husband, who was deported to Germany and presumably killed. She convinces herself that an amnesiac derelict in the neighborhood (Georges Wilson) is in fact her missing husband, lures him to her bar, and tries to jog his memory in various ways. Sadly, her success in restoring his identity becomes indistinguishable from the man’s recollection of his own humiliation and defeat — holding up his hands as if under arrest when his name is called, for instance — and the catharsis of Hiroshima is categorically denied. Ironically, though the innovative Hiroshima won only a couple of secondary prizes at Cannes in 1959, the doggedly old-fashioned and defeatist Such a Long Absence won the grand prize at Cannes in 1961: new thinking must have been about as popular back then as it is today. Decidedly pre-New Wave, this picture undoubtedly belongs in the same category as Peter Brook’s Moderato Cantabile (1960), one of the films in the Facets series I haven’t seen, coadapted by Duras from her own novel and starring Jeanne Moreau and Jean-Paul Belmondo. What was loosely called New Wave in 1960, these films indicate, probably looks more like Old Wave in 1995.

If Hiroshima is the first film to show Duras’ greatness as a writer, Nathalie Granger (1972) may be the first to show her greatness as a director. The uncredited producer is the neglected critic and filmmaker Luc Moullet, and it seems that some of his deadpan, melancholy wit has been imparted to this production. A minimalist feminist comedy in black and white that’s all about presence and absence, structured around drifting camera pans and tricky sound cues, it involves two women (Jeanne Moreau and Lucia Bose) and their mainly absent little girls — one of them called Nathalie Granger — in a country house. (There’s also a husband, who appears briefly in an early scene and then disappears without explanation.) One hears radio reports about a police manhunt for two teenage male killers and kidnappers in the area and sees a couple of cats in the house and backyard.

About the only scenes qualifying as “action” are two ineffectual visits to the house by a nervous but eager washing-machine salesman (played hilariously by Gerard Dépardieu in one of his earliest screen appearances) and the piano lessons given to the two girls once they appear. Additional contenders are an uneventful boat ride in the pond behind the house, an equally uneventful bonfire in the backyard, and a brief encounter between a girl with a baby carriage and a cat. But thanks to Duras’ masterful composing of sounds and images, Nathalie Granger kept me spellbound throughout and amused much of the time.

The minimal dialogue is all in sync, so the tricky sound cues have to do mainly with the piano, which is frequently heard offscreen when the girls are absent and it’s clear the two women couldn’t be playing it either. (At one point a cat proves to be the culprit; and later in the movie, when we finally see the keyboard during a piano lesson, part of what we hear being played is still offscreen.) The radio reports about the teenage criminals and intercut scenes of a teacher expounding on Nathalie’s “violent” misbehavior conjure up another kind of offscreen space, where it might be said that action is no less present just because it’s heard about rather than seen.

A typical deadpan, absurdist gag occurs when the phone rings, Moreau answers, and the woman on the line complains that “the oil hasn’t arrived yet.” “There is no phone here, Madame,” Moreau explains, then hangs up. Later on she confounds Depardieu in the midst of his spiel by declaring, “You’re no salesman.” He tries to prove otherwise by showing his business card, but she and Bose are adamant: “No, no,” they say over and over, though they don’t mind at all if he wants to come back later and try again, so he does.

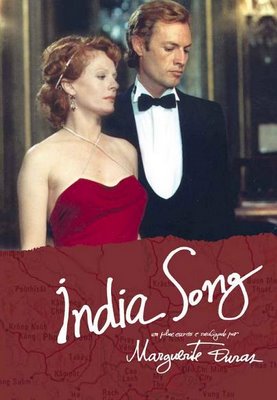

Many consider Duras’ best films to be India Song (1974) and Le camion (1977). Duras’ talent for sound tracks reaches its apotheosis in India Song: the sheer sensuality and density of the voices, music, and sound effects are so rich that the languorously beautiful 16-millimeter color visuals, which often involve actresses in evening dresses (including Delphine Seyrig) dancing with tuxedoed men (including Michel Lonsdale) in front of mirrors or reclining in despair on the floor, have to be taken mainly as accompaniment. This is surely the film in which Duras’ colonial erotics gets its fullest and most emotionally complex workout (over half the film takes place at a reception held at Calcutta’s French embassy in 1937), and the feeling of camp excruciation is held in perfect equipoise with the glamour and the class guilt by Carlos d’Alessio’s haunting “India Song Blues,” undoubtedly the most memorable tune ever to be heard in an avant-garde movie.

In contrast to Nathalie Granger, all the voices here are pointedly out of sync with the on-screen action, even though some of the people seen may be on the sound track. Duras gives us two versions of the past at once, one aural and one visual, and the audience has to negotiate between them as well as make various conjectures of their own. (This is one of the few films in the history of movies whose sound track was put together before shooting; in fact, the sound track was played back during filming so that the actors could coordinate their silent movements with it.) Agatha is marked by a similar division between sound and image, but its relative lack of richness in both the sound track (two voices, Brahms waltzes, and waves) and the visuals (empty beaches, Bulle Ogier, and Yann Andrea, Duras’ companion) ultimately leads to some monotony.

If memory serves, Le camion consists of only two kinds of narrative material: Duras reading aloud to Gerard Dépardieu a text about a film that might be made about a truck, a male truck driver, and a female hitchhiker; and a truck moving through a French landscape, accompanied at times by Beethoven’s Diabelli Variations and by Duras reading aloud from her text. Just as India Song situates itself in the painfully remembered past, Le camion plants its stakes in the conjectured future, where the audience is already waiting for it.

The best review of Le camion I know also happens to be the nerviest column Pauline Kael ever wrote for the New Yorker. To read it properly, you must go not to Kael’s recent compendium For Keeps, where the review is slightly shortened and deprived of its original context, but to her 1980 collection When the Lights Go Down: here her highly appreciative (albeit feisty) seven paragraphs about Le camion immediately follow a two-paragraph dismissal of Star Wars, which premiered in the same week. (When you’re finished reading that pungent combo, you might turn to Michel Chion’s Audio-Vision: Sound on Screen, a fascinating book published last year: in a single lucid paragraph he explains why India Song is cinematic and Le camion is televisual.) You might say that 18 years ago Duras and Kael both knew that Le camion had more to do with the future of movies than Star Wars, but nobody else was paying much attention. Now’s a good time to catch up with what these women were saying.