This review appeared in the November 6, 1987 issue of the Chicago Reader. J.R.-

MAMMAME

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed by Raoul Ruiz

Choreographed by Jean-Claude Gallotta

With the Emile Dubois Dance Company.

The more attention is paid to stylizing the screen, to make the quality of how it looks convey the meaning, the closer you get to dance, which is precisely that — the communication of meaning through the quality of movement. — Maya Deren

While it seems plausible, even likely, that Raoul Ruiz is currently the most inventive filmmaker working in Europe, one does not ordinarily go to his work looking for masterpieces. An obsessive doodler — in the same serious way, one should add, that the cartoonist Saul Steinberg is, combining philosophical and metaphysical wit with a penchant for rethinking the world so that it encompasses his boundless energies — Ruiz is blessed and cursed by never knowing when to stop. Indeed, one could argue that his interest in producing lively work, combined with his disinterest in producing masterpieces, has made him the most prolific and proliferating idea man to have emerged in the cinema since Godard. Born 11 years after Godard (1941) in Chile, Ruiz started work on his first feature the year after Breathless (1960), but it wasn’t until he became an exile in France, following the Chilean military coup of September 1973, that his career began to accelerate to Godardian proportions.

Now that his filmography runs to some 60 titles, half of which are feature-length or longer (in the case of a few TV miniseries), it becomes all the more striking that not one of them has yet received anything resembling normal distribution in this country. But distribution depends on packaging, and Ruiz does not package himself for stateside consumption. The eccentric filmmaker in the U.S. who wants to make marginal films invariably has to adopt the badge or shield of a school or genre — art film, “independent film,” experimental film, punk film, “cult film,” feminist film, animated film, documentary, academic theory film — in order to secure financing, at one end, and distribution, promotion, and criticism at the other. (Major filmmakers who manage to elude or straddle these categories — Leslie Thornton is an outstanding example — are characteristically treated as nonpersons in the media; they fall between the cracks.) Ruiz, on the other hand, needs only to accept the institutional framework of state funding, as channeled through European television and art centers, and he automatically acquires a commission and an audience without having to settle on any binding affiliation or label beyond the open-ended rubric of “art” or “culture” or “education.” Consequently, the sheer existence of his massive, varied work constitutes a genuine affront to the capitalist definitions of art and experiment that govern our culture.

***

There have been occasions when Ruiz might have made some inroads in the U.S. market, had he agreed to scale his work down to acceptable art-house proportions. When he made Three Crowns of the Sailor (1982) and City of Pirates (1983), both of which showed at the New York Film Festival, it was suggested that either of these features might be picked up by distributors if Ruiz would consent to trim them; reportedly Valeria Sarmiento — his wife and usual editor, and a filmmaker of interest in her own right — proposed a version of Three Crowns with this in mind. But faced with such options, Ruiz has generally preferred to start a new feature instead. And since he became codirector of the Maison de la Culture in Le Havre two years ago, with an annual budget of about 20 million francs, his activities have expanded to include producing films by other directors; overseeing various theater, music, and dance projects; directing his own stage productions; and sometimes combining elements from the above to generate new films. Life Is a Dream and Mammame, his two most recent features, are both products of this new setup.

Of the two dozen Ruiz films I’ve managed to see, Mammame, running only 65 minutes, is the first to have been disciplined, rather than merely inspired or informed, by an external structure — a dance performance choreographed by Jean-Claude Gallotta and performed by Gallotta with eight other dancers, four women and four men. The dance is an essentially plotless series of encounters, interactions, and collective endeavors among and between the dancers, none of whom stands out as a protagonist or star. Ruiz treats the choreography as a found object, translating the material shot by shot and move by move into a dance that can exist only on film. While it becomes impossible at many junctures to imagine what this choreography looked like in its original form — many of the unconventional angles and spatial transitions are unthinkable onstage, and Ruiz eventually shifts the dance to an outdoor location — it remains clear that Gallotta’s choreography has dictated Ruiz’s decisions every step of the way. Thanks to this discipline and structure, Mammame is not only the first incontestable masterpiece by Ruiz that I’ve seen, it is also his most accessible work, needing not a single subtitle nor any form of specialized knowledge. It rivals The Red Shoes as the most intoxicating dance film ever made.

Although Ruiz can be compared to Godard as a phenomenon, the figures who have influenced him most as a thinker and filmmaker are probably Jorge Luis Borges (intellectually and conceptually, if not politically) and Orson Welles (visually and formally). Like certain other Borges-inspired practitioners of Latin American Magical Realism, Ruiz regards somewhat skeptically the conventional notions of what is “real” and what is imaginary (though the political orientation of his agnosticism is closer to Marxism than to Borges’s conservatism). Ruiz also shares with Borges a taste for Victorian fantasy and adventure — Carroll, Stevenson, Chesterton — that is most apparent in his remarkable miniseries for Portuguese TV, Manuel on the Isle of Wonders (1984); his cherished boy’s-adventure motif of a model train traversing the screen on toy tracks, first introduced in Manuel, also makes dreamy reappearances in Life Is a Dream and Mammame.

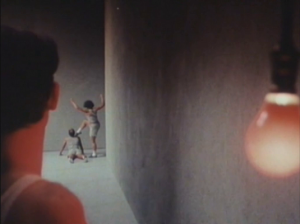

As for the Welles influence, one can readily perceive it in the first shot of Mammame — an extreme low-angle and wide-angle shot, monumental in its feeling of weight and gravity, of dancers flying past the camera in broad leaps. But it is equally evident in the deep focus, which creates cavernous distances and angular geometries between background and foreground figures; in the chiaroscuro lighting effects (including shadows and silhouettes, brilliantly realized by Acacio de Almeida’s camera); and in a magician’s sense of space and decor that plays constantly with our orientation, creating what Manny Farber has described (in reference to Welles) as space that is “prismatic and a quagmire at the same time.” In effect, this spatial ambiguity fits hand in glove with Borgesian doubts about reality, as is reflected in Ruiz’s own synopsis for Mammame: “A group of people who know each other, perhaps work together, are cinematically transported to a spot halfway between a large tent on a science fiction desert and the ballroom of a submarine, in a film about doubt, full-fledged doubt. . . .”

If Borges and Welles share both a notion of the labyrinth and a Scheherazade-like role as a teller of tales, it is worth noting that they are both also essayists, inside and outside their labyrinthine fictions: essays such as “New Refutation of Time,” F for Fake, and Filming Othello create fictional spaces, while overt fictions such as “Theme of the Traitor and Hero,” Citizen Kane, and The Magnificent Ambersons develop essayistic conceits. Ruiz is very much involved in the same sort of enterprise. Whether his films are fiction (City of Pirates), nonfiction (Of Great Events and Ordinary People), or some inspired conflation of the two, as in Mammame, they invariably combine fantasy and reflection.

To the degree that one can speak of fictional and nonfictional configurations in dance, Jean-Claude Gallotta’s energetic choreography is similarly mixed. Encompassing ballet as well as modern dance movement, it can be described as abstract, yet it is anything but nonrepresentational. An anthology of everyday human gestures and encounters, bursting with minidramas, it uses the dancers’ voices as frequently as their bodies — as an extension of their dance rather than as a mere accompaniment to it — although their utterances, which range from whispers and mumbles to chatterings and shouts, are all essentially nonverbal, closer at times to scat-singing than to speech. The film’s use of direct sound is fundamental to its sense of immediacy, enhancing the physicality of the dancers and the dance, but the various uses of prerecorded, offscreen sound — including music, the sounds of water, and occasionally the dancers’ voices as well — are no less important, enhancing what might be called the metaphysicality of the performance.

The interplay between documentary and fiction erupts in a number of other ways. Because Ruiz is not only recording a dance performance, but collaborating with it and rethinking it on a shot-by-shot basis, making each shot an event in itself, the extent to which he is documenting or “fictionalizing” the original text of Gallotta’s choreography remains a perpetually open question. By beginning the film on an artificially controlled theater stage — a veritable test-tube environment — and ending it in nature, on a spectacular seaside location where the dancers have to compete with a heavy wind and the sounds of bird cries and crashing waves, he raises the issue of which setting brings us closer to the reality of the dance, and which brings us closer to the fictional world that is generated in both settings.

To complicate the game, Ruiz intermittently shows us real water dripping and watery shadows onstage to go with the watery sound effects, and in one eerie shot he shows us the auditorium of empty seats behind the dancers, as if to remind us fleetingly of where we are. (The dancers nearest the seats take a bow at this point, and then the dance resumes.) And on the beach at the end, the dialectic between stylized and unstylized movement periodically vanishes: one couple interrupt their duet to look at the ocean, then continue the dance; offscreen music and various props (furniture, lemons on a table) figure in this brief final section as well.

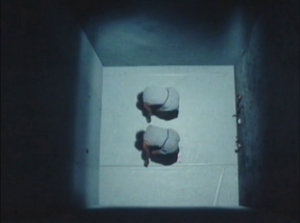

No film I have ever seen, including those of Yasujiro Ozu and 2001: A Space Odyssey, makes me more aware of the floor than Mammame. Thanks to the endlessly mutable overhead space manipulated by Ruiz, the floor becomes the spectator’s only anchor before the film finally breaks outdoors, and in disorienting high-angle shots, looking down on some of the dancers inside a cell-like enclosure onstage, it becomes the equivalent of a backdrop as well. There is no corresponding sense of ceilings; when Ruiz offers reverse-angles from the floor of the enclosure, and one sees, behind the towering dancers, the faces of other dancers high above them, looking down and muttering their nonverbal comments like spectators peering down a well, one perceives only darkness and open air behind them. In other places, Ruiz will accentuate the long stretch of the stage/floor by positioning objects — mushrooms on a wall, a telephone with a long, receding extension cord — in the extreme foreground. More generally, he seems to favor this literally grounded sense of space in order to highlight the freedom and effort of all the activity done in defiance of gravity, so that the floor inside functions rather like the wind outside — as a force of nature and reality against which all the other elements can be built and measured.

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

Writing about Mammame in Cahiers du Cinéma, Iannis Katsahnias argues that the pleasures of Ruiz’s cinema — his storytelling gifts, the enchanted nature of his special effects, and his rhythm — are personal and obsessive variations on what we expect from Hollywood movies. And while Ruiz displays none of the cinephile film references that we associate with his New Wave colleagues — his applications of Welles are at once too extensive, too quirky, and too integrated to qualify as hommages — his intricate uses of everyday objects in Mammame as props and décor, combined with the calisthenic energies of the dancers, gives this film some of the exhilaration that we find in the best American musicals.

These objects, to be sure, never attain the naturalistic context of Hollywood props. Not even the lemons that appear on the cliff register as found objects; and the appearances onstage of green vegetation, a mattress with rumpled sheets, clothes on a line, a ladder, and two parked cars never approximate Gene Kelly’s use of a lamppost in the title number of Singin’ in the Rain. But the landscapes of these two films are similarly infectious in their dreamlike elation; and the dialectic of Mammame‘s magical stage machinery is reminiscent of the musical’s number “You Were Meant for Me,” which lays bare the artifice of Hollywood on a studio soundstage, then snares us in the artifice all over again.

Perhaps the greatest tribute one can pay to Ruiz’s sense of invention in Mammame is to point out its power to transform the unexceptional. At one point we hear a fly buzzing around the stage; at another, Ruiz frames the dancers onstage in a conventional, symmetrical composition. Yet because of the creative deliberation that is felt everywhere in the film, both of these moments register as privileged and integral rather than as lapses or accidents. Whether arrived at by chance or design, that fly and that conventional camera setup are as essential to Mammame as all the stylized artifice surrounding them; and just as all the ideas in the film are subsumed in the physicality of the dance, these choreographic incursions register with the beauty of pure Idea.