From the Chicago Reader (December 2, 1988); also reprinted in my collection Essential Cinema. — J.R.

THE DEATH OF EMPEDOCLES

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed and written by Jean-Marie Straub and Daniele Huillet

With Andreas von Rauch, Howard Vernon, William Berger, Vladimir Baratta, Martina Baratta, and Ute Cremer.

Three pretentious but relevant quotes: “Aesthetics are the ethics of the future” (Lenin). “To make a revolution also means to put back into place things that are very ancient but forgotten” (Charles Peguy). “When the Green of the Earth Will Shine Freshly for You” (Jean-Marie Straub and Daniele Huillet’s subtitle for The Death of Empedocles).

For spectators who don’t know what to do with their films, Jean-Marie Straub and Daniele Huillet offer a rigorous program that’s all work and no play — a grueling process of wrestling with intractable texts, often in languages that one doesn’t understand, without the interest provided by easy-to-read characters or compelling plots. But in fact every one of Straub-Huillet’s 15 films to date (10 features and 5 shorts) offers an arena of play as well as work, and opportunities for sensual enjoyment as well as analytical reflection. To find this arena of play and pleasure, one has to go beyond what we usually associate with the enjoyment of culture–beyond parameters that are usually limited by mutually exclusive notions of “art,” “entertainment,” “education,” and “scholarship,” notions that generally make us smile or groan in advance, regardless of what is placed in front of us.

Among the intellectuals in Europe who make marginal films (as opposed to the more widely circulated “art films” of Godard, Ruiz, Kluge, et al), Straub and Huillet are in many ways the most respected, but their works are seldom dealt with in the U.S. Utopian Marxists with a taste and passion for nature, antiquity, direct sound, and obscure, mainly neglected texts, they remain materialist thorns in the sides of those critics and programmers who believe that films are meant to be consumed rather than grappled with.

It’s taken two years for The Death of Empedocles, the couple’s latest feature, to cross the Atlantic, and, apart from a single screening in Berkeley six weeks ago, its appearance here at Facets Multimedia represents its U.S. premiere. (That Facets is running it for a whole week probably also makes this the first “commercial” run Straub-Huillet have had in the U.S. since Moses and Aaron opened in New York in 1975.) The handful of American colleagues I know who have seen Empedocles, in Berlin or Paris in 1986, have dismissed it as Straub-Huillet’s least rewarding and/or most “punishing” feature. I think they’re dead wrong about this, but I have to admit that the film is likely to be unrewarding or worse if approached with the wrong frame of mind or set of expectations.

The conflicts, textures, pleasures, and meanings of all Straub-Huillet films are created in the encounter of one or more preexisting texts (verbal or musical) with concrete places — settings or landscapes. In each film the complex balance of the encounter is distinctly different. The texts have ranged from fiction (by Bertolt Brecht, Heinrich Boll, Marguerite Duras, Franz Kafka, and Cesare Pavese) to poetry (by Saint John of the Cross and Stephane Mallarme); from plays (by Ferdinand Bruckner and Pierre Corneille) to letters (by Friedrich Engels and Arnold Schoenberg); and from political statements (by Franco Fortini and Mahmoud Hussein) to musical pieces (by Bach and Schoenberg). The locations have included urban and rural landscapes in Egypt, France, Germany, and Italy, as well as shots in New York and Saint Louis to supplement the mainly German footage of Amerika/Class Relations, their 1984 Kafka adaptation.

Some Straub-Huillet films use musical texts (notably their 1967 Chronicle of Anna Magdalena Bach) and some use both musical and verbal texts (their 1972 Introduction to Arnold Schoenberg’s Accompaniment to a Cinematographic Scene, and their 1975 film of Schoenberg’s opera Moses and Aaron). The Death of Empedocles might be described as their first fully musical film with only a verbal text. The highly metrical blank verse of Friedrich Holderlin (the first of three versions of an unfinished verse tragedy, written in 1798) becomes in effect the libretto for an opera or oratorio that uses the chance contributions of the wind, insects, birds, plants, clouds, and sun as orchestral accompaniment. (There’s also the barking of an offscreen dog and, behind the opening and closing credits, bursts of actual music as well as thunder.)

The pleasure to be found in the sound of Holderlin’s text — which is performed in rural locations in Sicily near Mount Etna is in a way unprecedented in Straub-Huillet’s work. Their 1969 adaptation of Corneille’s Othon on a Roman hilltop surrounded by contemporary traffic was largely an exercise in comic distancing effects: the lines were delivered (rather than acted) by mainly non-French actors at breakneck speed and with little expression, accompanied at times by lengthy camera movements and at many other times by ambient distractions ranging from the splash of a nearby fountain to the growl of a passing motorcycle. Poems by Saint John of the Cross were used for dramatic recitations in The Bridegroom, the Comedienne and the Pimp (1968), but these were only some of the materials used in a densely compacted narrative structure. In Every Revolution Is a Throw of the Dice, (1977) a group of nine men and women recited Mallarme’s “A Throw of the Dice Will Never Abolish Chance” while seated in Paris’s Pere Lachaise cemetery near a plaque commemorating the Paris Commune victims of 1871; but here again the delivery was comically poker-faced.

It was in their hilarious 1982 short En rachachant, based on a children’s book by Marguerite Duras, that Straub-Huillet began to make use of expressive acting in the conventional sense — a practice developed further in Amerika/Class Relations two years later. The fully acted The Death of Empedocles benefits from this experience. Some of the actors are non-German, which leads to an accented delivery of the sort that Straub and Huillet have often favored whether the spoken language has been French, German, or Italian. But here the rhythmic delivery of the lines has a physical presence, and the film undertakes a voluptuous exploration of German’s various tonalities that virtually reinvents the language. The sound of German (which I neither read nor speak) has usually been somewhat harsh and abrasive to my ears, but The Death of Empedocles manages to make the language sing with a depth and beauty that I’ve never heard before. Clearly this is a richly textured music that belongs to Holderlin, but Straub and Huillet have conducted it with a special feeling for both its potential drama and its range of tones and cadences; moreover they have recorded it live in such a way that it blends pleasurably with the ambient sounds of nature without ever being overpowered by them.

This, too, is relatively new in Straub-Huillet’s work. As they have progressively developed and refined their filmmaking methods, the power and resonance of the places they film — above all, rural Italy in From the Cloud to the Resistance (1978) and Cairo and rural Egypt in Too Early, Too Late (1981) — have sometimes threatened to overwhelm their texts, or at least to take the upper hand. Far from damaging the films in question, this imbalance has strengthened their capacity to teach us how to look and listen. “Attending to” a text is partially what these films are about, and this is admittedly an activity that requires a certain amount of work. But “attending to” a place is just as important, and in the case of these two films, it involves an equal amount of play — a freedom to drift through, circle around, meditate on, cast about in, and sensually enjoy (as well as think about) the physical reality that is recorded on film with such tact and precision.

These priorities are altered somewhat in The Death of Empedocles — not because its locations are less than beautiful, or inappropriate as settings for the verse, but because the principal undirected pleasure of this film is found more in the text itself, as it’s delivered, than in the places that enclose its performance. In Too Early Too Late, long lingering looks at the Egyptian countryside traversed by villagers and animals provided a kind of lens through which one could read an offscreen recitation of Mahmoud Hussein’s text. In The Death of Empedocles, Holderlin’s text provides a lens through which we can “read” the natural landscape of Mount Etna and environs (which, by the way, are beautifully shot in 35-millimeter by Renato Berta).

So far I’ve said next to nothing about the (minimal) plot and (elusive) meanings of The Death of Empedocles (text and film). Straub-Huillet use a version of the play that’s unavailable in English, and I’ve only been able to see the film once. A few clues are nevertheless in order:

The Concise Columbia Encyclopedia has the following to say about the historical Empedocles: “c.495-c.435 B.C., Greek philosopher. He held that everything in existence is composed of four underived and indestructible substances — fire, water, earth, and air — and that atmosphere is a corporeal substance, not a mere void. He believed that motion is the only sort of change possible and that apparent changes in quantity and quality are in fact changes of position of the basic particles underlying the observable object. Thus he first stated a principle central to modern physics.” Empedocles was also a statesman who lived in the Sicilian town of Agrigentum; he came into conflict with the citizens of that town and ultimately killed himself by leaping into the crater of Mount Etna.

According to critic L.S. Sulzberger, Holderlin’s main source about Empedocles was a work by Diogenes Laertius, but “at the same time his hero is the favorite child of his own imagination. Empedocles, poet, magician, prophet, political reformer and savior of his people, exemplifies the genius as Holderlin imagined him.” He can also be described from Holderlin’s vantage point as “a disciple of Rousseau,” an embodiment of “that human self-consciousness and reason characteristic of a contemporary of Kant’s,” a mediator between the realms of nature and art, a Hegelian hero who emerged in a time of crisis to resolve the conflicts of his age, and a figure in some ways comparable to Goethe’s Faust. (A contemporary of Hegel and Goethe — as well as Kant — Holderlin had personal dealings with both.)

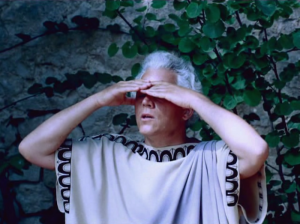

Clearly a mystic, Holderlin’s Empedocles (played in the film by Andreas von Rauch) is accused of blasphemy by two of the town’s representatives, the priest Hermocrates (Howard Vernon) and the political leader Critias (William Berger), who incite the populace against him and drive him into exile with his young disciple Pausanias (Vladimir Baratta). The blasphemy of Empedocles consists of his claim to be divine, which Holderlin interprets as a flaw of genius — loving the gods too intensely and therefore identifying too closely with them. Empedocles’ punishment for this presumption is that he no longer is able to serve as the gods’ mouthpiece. Other characters of importance include Panthea (Martina Baratta), the daughter of Critias, and her somewhat older friend Delia (Ute Cremer), who discuss Empedocles before and after his expulsion from Agrigentum.

In the second act, as Empedocles approaches Mount Etna, the citizens of the town change their minds, intercept him and Pausanias, and try to persuade him to come back as their ruler. Empedocles angrily refuses their offer and announces that he is determined to die, offering himself as a sacrifice for the redemption of his fellow men and thus renewing his spiritual function as a link between mortals and gods. (If Holderlin had completed this or his two subsequent versions of the play, presumably three more acts would have followed before Empedocles leaped into the volcano.)

The film opens, after a brief shot of trees and grass, with Panthea and Delia, shown in separate shots, conversing in what they describe as Empedocles’ garden. Each character looks offscreen at the other, but the editing of the separate shots is disjunctive. As they frequently do (most notably in History Lessons, 1972), Straub and Huillet break the usual continuity rules for cutting between the offscreen looks of conversing characters, obliging the spectator to construct the space between the characters rather than accept it as a given. This leads to an ironic and surprising effect when, in the middle of a speech by Panthea, the two characters are finally brought together in the same frame, and we discover that they’re standing less than three feet apart.

One probably shouldn’t interpret such an effect too literally; Straub-Huillet’s unconventional handling of space has always been part of a broader project to deprogram our expectations. But the isolation of certain characters from one another (Empedocles from the town leaders, the women from the men) is generally adhered to so rigorously that exceptions to this rule — such as shots showing Empedocles with Pausanias, or the town leaders with each other — often register as privileged moments. As a rule, the conflicts between spiritual and social concerns, and between self and community, seem to determine the placement of characters, and the sudden pairing of Panthea and Delia in the same shot may imply that their separate positions–moral and social as well as spatial — are closer than we initially assume them to be.

In a subsequent scene between Panthea and Delia, however — after the expulsion of Empedocles, when the difference between their positions is handled more dramatically — the relation of each character to the natural surroundings becomes more pertinent. The two women are seen both separately and together, and their conflicting attitudes about Empedocles and what he represents are graphically illustrated by their separate positions. Delia stands under a shaded tunnel formed by two rows of trees (except when she steps forward to embrace Panthea or to kneel at her feet), and Panthea stands at the edge of this tunnel with the sky and sun-soaked greenery behind her. The orderly, man-made enclosure formed by the rows of trees suggests the shaded comforts and confinement of society itself. The freedom and obstinacy of Panthea in the open air (“I honor him, yes, and if you do not know it, I say it to your face”), combined with her refusal to budge, calls to mind the stubborn intransigence of Carl Dreyer’s Gertrud in relation to the demands of her own society, and in this respect Panthea resembles the white-haired Empedocles himself.

The difficulty posed by The Death of Empedocles for some of Straub-Huillet’s former partisans (one of whom told me that “it makes Moses and Aaron seem like The Sound of Music“) probably has something to do with its relative visual stasis. If memory serves, camera movement is entirely absent (or at best restricted to a few brief pans), and the rigorous framing — which always has the effect in Straub-Huillet films of making separate shots register with the weight of enormous blocks of concrete — often seems to be drawing the tragedy to a standstill, whether the camera is trained on characters, landscapes, or characters and landscapes together.

But the appearance of stasis is deceptive. Three elements in the film are in virtually constant motion: Holderlin’s text, the actors’ gestures, and nature — the wind in the trees, passing clouds, sounds of life, changes of light. And the juxtaposition of these movements with static camera setups is essential to the film’s music and rhythm.

The abstract density and difficulty of the verse undoubtedly poses another potential stumbling block, but there are many possible ways of dealing with it. Barton Byg’s subtitles are selective rather than exhaustive, and can probably be read more fruitfully as footnotes than as a substitute for the full German text, which remains the film’s richest source of sensual pleasure. Part of Straub-Huillet’s achievement is to dramatize this text well beyond any possible silent reading of it by giving it a maximal physicality in sound, emotion, and gesture. And because so much of the text is concerned with the physicality of nature (as well as the four elements), the static camera setups function musically in a way that is analogous to pedal points; like sustained or suspended chords, they allow the melodies of the verse and the countermelodies of the surrounding natural sounds to take root. (Significantly, many of the characters’ exits are heard offscreen rather than seen; Straub and Huillet often follow Robert Bresson’s avowed practice of replacing image with sound whenever possible.)

Although Straub and Huillet are utopians in the sense that they make their films for ideal spectators, the fact that none of us is an ideal spectator shouldn’t leave any of us out in the cold. Perceiving the world is a formidable enterprise without the diverse clues offered by art, and the ultimate accomplishment of Straub and Huillet is to make the task easier, not harder.

Their radical definition of art includes an extraordinary sense of openness as well as of closure, and even counters our sense of what constitutes an integral work. The version of The Death of Empedocles being shown in Chicago is actually only one of four that were shot and released: each version was shot in the same language, with the same actors and camera setups, but each one uses different takes of each shot, which means that the interventions and contributions of nature differ. For instance, the barking dog heard offscreen in this version (which was also shown in France with French subtitles) is not heard in the first version or the third; however, the first version does feature a lizard crossing the ground in the scene that shows Empedocles freeing his slaves, and in the third an offscreen rooster crows during one of Empedocles’ speeches. The implication is that masterpieces are neither as fixed nor as impervious to chance as we ordinarily suppose; instead of assuming that art should work against the vicissitudes of nature, we might welcome a natural world in which an obscure German poet and a distant mountain can equally find their place.