From the Chicago Reader (May 18, 1990). — J.R.

MR. HOOVER AND I

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed and written by Emile de Antonio.

1. “Born Pennsylvania U.S.A., in intellectual surroundings and coal mines. Went to Harvard. Became, and still is, a Marxist, without party or leader. Started making films at age of 40 after having avoided films most of his life. Favorite film is L’age d’or.” Emile de Antonio’s self-description was written around 1977 for a poll organized by the Royal Film Archive of Belgium and eventually published in book form as The Most Important and Misappreciated American Films. Under the category of most important American films, de Antonio listed, in order, The Birth of a Nation, It’s a Gift, A Night at the Opera, The Cure, The Immigrant, One A.M., The Kid, Big Business, The Navigator, and Foolish Wives, and added the following comment:

“Most American films were and are like Fords. They are made on assembly lines. John Ford is not an artist any more than Jerry Ford is a statesman. Harry Cohn said it all and the Capras jumped.

“Comedy was spared all that. Irreverence was possible because the booboisie didn’t know it was being laughed at.

“American films have been seen too often. I rarely go to the movies.”

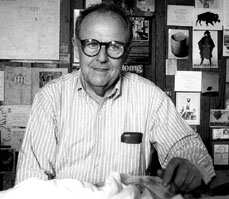

Under the category of misappreciated American films, de Antonio listed five of his own: Point of Order (1963), In the Year of the Pig (1968), Millhouse: A White Comedy (1971), Rush to Judgment (1967), and Painters Painting (1973).

2. Before seeing Mr. Hoover and I (1989), my attitude toward the work of Emile de Antonio was always a bit confused and uncertain. I admired his first film, Point of Order — a remarkable reorganization and distillation of 188 hours of kinescopes of the 1954 Army-McCarthy hearings into about 90 minutes that reinvented the meaning of Joseph McCarthy for subsequent generations. But my spotty sense of de Antonio’s later work led me to view him as a courageous radical and intellectual who was more a polemicist and invaluable 60s gadfly than an artist. I knew that some of my non-American friends whose politics and aesthetics I highly respected regarded him as the greatest and noblest living American documentary filmmaker, but having seen only Point of Order, Millhouse, and Underground (directed with Haskell Wexler, 1975), I found it difficult to see precisely what they meant. Millhouse had the nerve to shower Nixon with abuse and scorn when he was at the height of his power as president — de Antonio was the only filmmaker on Nixon’s notorious “enemies” list — and Underground performed the valuable and audacious service of interviewing the Weather Underground at a time when they were the FBI’s most sought-after radical fugitives. But both of these films seemed more meaningful as potent contemporary gestures than as lasting works of art that genuinely explored the possibilities of the medium. Having lived abroad for almost eight years, I’d managed to miss such films as In the Year of the Pig, America Is Hard to See (1969), and Painters Painting, and after I returned, I hadn’t made it to In the King of Prussia (1982) either.

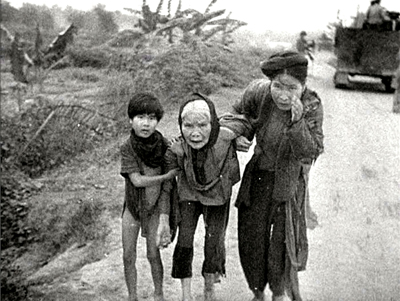

Seeing the fascinating and hugely entertaining Mr. Hoover and I at the Toronto film festival last fall, about three months before de Antonio died of a heart attack at age 70, made me seriously rethink my ideas about him. I’ve seen the film several times more recently, and encountered for the first time on tape some of the de Antonio films I had missed. In the Year of the Pig is the first and best of the major documentaries about Vietnam, infinitely superior to the better known Hearts and Minds — and perhaps the only one that’s truly about Vietnam, not this country’s national ego. I also saw the (to me) disappointing and relatively conventional Painters Painting. I can’t pretend to assess his career as a whole here because I’m still discovering or rediscovering parts of it, but I can at least say that Mr. Hoover and I, a singular and remarkable testament, has made me realize the importance of forming this acquaintance.

3. The issue for me in de Antonio’s work has never been intelligence — his films are nothing if not intelligent — but filmic intelligence. The editing of Point of Order certainly has this filmic intelligence, and so does the powerful beginning of In the Year of the Pig, but in both instances it was a matter of creatively manipulating archival material. When it comes to shooting material of his own, de Antonio seems to regard the camera as a mechanism for recording talking heads rather than as an expressive tool in its own right; that is, his intelligence figures mainly in his decisions on what to shoot and how to edit, not in how to shoot.

Mr. Hoover and I seizes on the talking-head principle even more nakedly and relentlessly than the other films, and because the talking head in this case is mainly de Antonio himself, one might assume this to be his least “cinematic” movie. In fact, because of the way that it’s conceived and executed — shot, spoken, and edited — it turns out to be his most cinematic movie, a film that calls attention to its own construction as a film in a way and to a degree that its predecessors do not. It is a work that declares de Antonio’s allegiance to the minimalism of his friends in the New York art world, such as John Cage and Andy Warhol, and as in their best work, it doesn’t adopt minimalism merely as an aesthetic pose but as a functional means to achieve clarity.

4. Back in the mid-60s, Susan Sontag wrote in praise of Point of Order that it “aestheticized a weighty public event.” Mr. Hoover and I aestheticizes a weighty private event — de Antonio encountering the tens of thousands of pages devoted to him in his FBI file. He aestheticizes it by juxtaposing the clarity of minimalism with the internal and external obfuscation practiced by J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI bureaucracy. The film emerges as an autobiography that dialectically and persuasively defines itself as a sane countertext to the demented biography of de Antonio compiled by the FBI. (One hilarious example among many: Around the time that he was applying to flying school, de Antonio had lunch with a respectable friend who asked him, “Now, De, what are you really going to do when you grow up?” “I think I’d like to be an eggplant,” he replied, and roughly three decades later, he came across this statement solemnly recorded in his FBI dossier.)

Point of Order compelled us to study the aesthetic strategies of both Joseph McCarthy and his opponents; Mr. Hoover and I foregrounds the aesthetic strategies of Hoover and de Antonio. Both films, in the final analysis, teach us how to reach political conclusions in the act of carrying out our criticism of art.

5. For all its off-the-cuff appearance, Mr. Hoover and I had an unusually long gestation period. In an interview with Alan Rosenthal originally published in 1978, de Antonio alludes to “a fictional film I want to do about my own life. It began as an obsession and I started thinking about it before we did the Weather film [Underground]. It began with my suing the government under the Freedom of Information Act.” De Antonio then describes the experience of receiving the first installment, “almost 300 pages of documents collected by the FBI on my life up to my 24th year.” The file was “initiated by my applying for flying school and a commission” and went all the way back to the year he went away to prep school at the age of 12. De Antonio added that he was planning to tell this story “very dispassionately,” and that he was “doing it as a fiction because of the libel laws.”

Obviously the project went through significant changes over the next 15 years or so, including the elimination of a fictional form, but the root idea — de Antonio receiving his own FBI file — remained the same. In its final form, the film contains eight different kinds of documentary material:

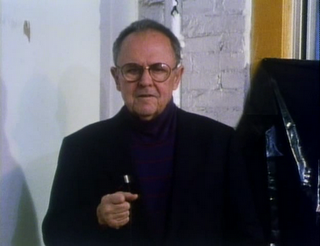

(1 and 2) De Antonio addressing the camera on what appear to be two separate occasions in a neutral urban interior, probably his own New York apartment.

(3) De Antonio addressing a college audience and responding to questions after a screening of Point of Order; some references to the Iran-contra hearings make it clear that the date is 1987 or later.

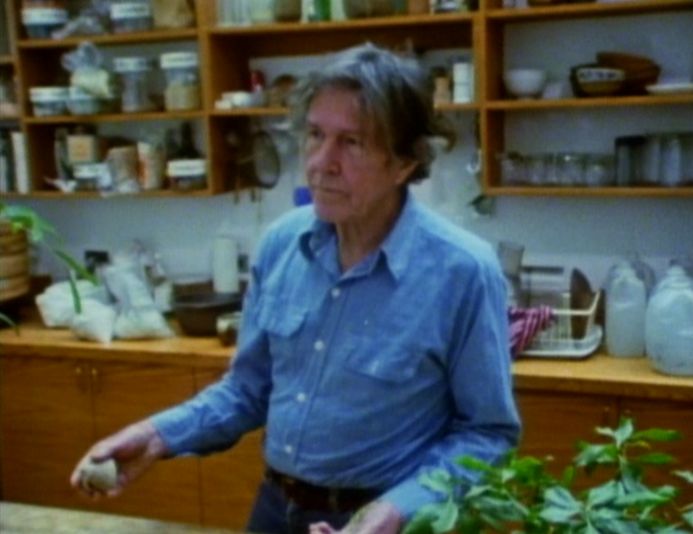

(4) De Antonio asking John Cage about indeterminacy as an aesthetic concept and method in a kitchen while Cage is preparing bread. This material, one should note, was shot not by de Antonio but by the Canadian filmmaker Ron Mann (Comic Book Confidential, Imagine the Sound), and is an outtake from Mann’s 1985 documentary Poetry in Motion.

(5) De Antonio chatting with his wife at home while she gives him a haircut.

(6) A brief clip of J. Edgar Hoover and Richard Nixon at a ceremony in which Hoover presents President Nixon with a badge making him an honorary member of the FBI; joking allusions are made to Nixon’s unsuccessful job application to the FBI in 1937.

(7) Still photographs of Hoover.

(8) Shots of various portions of FBI documents.

The first through fifth types are autonomous blocks of material intercut with one another throughout the film. The sixth, the only archival footage, appears as a separate chunk somewhere in the middle (followed by a commentary from de Antonio). And the seventh and eighth are used sparingly to illustrate and punctuate de Antonio’s commentary (a photograph of Hoover as a child, however, is the first thing we see in the film).

Isolating these separate blocks is important because a central part of the film’s method is to make us aware of their distinctness from one another. At the same time, de Antonio freely cuts both within and between them in order to follow a single line of argument — a line that begins with the subject of himself and Hoover and then branches out to explore separate facets of each — and he doesn’t always respect the chronological progression of each sequence. Very long takes predominate at the beginning of the film; by the end, the cuts have become much more frequent.

6. After the title, de Antonio, in a sweater and jacket, says to the camera, “If I were asked to choose a villain from the history of this country, it would not be Benedict Arnold, nor would it be communist conspirators, nor would it be spies for the Nazis — because, except for Arnold, most of these people were fairly impotent, did not have power to do anything. But Hoover, because he had power for such a long period of time, because it was wantonly exercised, because it was exercised with spite, without a touch of judgment or any sense of justice, because it was willful and capricious, because it made a mockery of our Constitution . . .” His sentence is broken off by a jump cut, followed by de Antonio saying, “Don’t cut. We’ve cut by saying that, of course. We’re running?” An offscreen voice says “Yeah,” and de Antonio starts a new sentence about Hoover.

A bit later we get another disruptive cut, to John Cage putting corn oil and then bread in a pan while he describes the various things he is doing. Only toward the end of this sequence does the camera move around to reveal that Cage is addressing de Antonio on the other side of the counter, and only after that does de Antonio bring up the fact that they’re supposed to be talking about indeterminacy — at which point there is a cut back to de Antonio in his jacket and sweater talking about Hoover.

A little further on, after de Antonio, in the college auditorium, has been comparing the Army-McCarthy hearings to the Iran-contra hearings, there is a cut to de Antonio saying, while we hear the mechanical sound of the camera, “This film, although it probably won’t be seen by many people, is an attempt at subversion. This film is a film about position. I’m glad we’re hearing the sound. Why should the process of any art not be included in whatever that art is?”

All three of these disruptive cuts function as slight pivots and digressions in the discussion rather than as irrelevant interruptions. In the first and third, we’re alerted to the filmmaking process, a modernist gesture that prepares us in turn for the introduction to Cage, who like Warhol can be described as one of the last of the modernists. (Minimalism — from Beckett to Cage and Warhol — can be described as the last gasp of modernism, before postmodernism took over.)

7. The spectacle of Cage preparing bread, which constitutes the second apparent interruption, eventually becomes part of the discussion about the uses of indeterminacy in art, a discussion that’s pursued by Cage and de Antonio in later portions of the same kitchen dialogue. Cage’s cooking functions not merely as a counterpoint to the conversation but, at certain points, as an unwitting illustration of the nature of artistic choices, Cage’s as well as de Antonio’s. For example, when Cage is carefully sweeping cracked wheat off the counter into a container while discussing indeterminacy, he sprinkles a few leftover bits over the bread he has just prepared.

De Antonio does not employ in Mr. Hoover and I the chance operations used by Cage in determining certain aspects of composition and performance — as de Antonio himself emphatically pointed out to me and others when he discussed the film at various venues last fall. He never said how such operations did relate to what he was doing. Cage’s meaning and function in the film are both mysterious and subtle, but I would argue that they are not simply ineffable. Cage’s role as friend and educator to de Antonio is recounted in one of de Antonio’s monologues, along with a beautiful Zen koan that Cage told him, circa 1953. De Antonio says this koan was as important to him as anything he learned from Marx, Hobbes, Plato, or Schopenhauer, but I won’t attempt to repeat it here — de Antonio does a much better job of it than I possibly could. Still, I think it has as much bearing on the structure and meaning of the film as Cage’s work in composition and performance had.

Broadly speaking, Cage’s artistic principles are founded on the notion of removing the artist’s volition at certain stages and allowing a sort of dialogue with “nature” or “the universe” or “fate” that is brought about through the introduction of chance operations. (At one point in the discussion, while talking about intervals, Cage describes his use of astronomical maps in relating musical notes to stars; it might be added that this film does make frequent use of the notion of intervals, if not indeterminacy.) The only way in which de Antonio might be said to duplicate or imitate Cage’s methods is his use of Ron Mann’s footage.

But it might also be argued that life itself exercised this indeterminacy over de Antonio’s own rather haphazard career — a career that can be regarded as itself an intricate struggle between chance and control. Before he became a filmmaker, de Antonio worked at various times as a longshoreman, barge captain, peddler, war surplus broker, book editor, and college philosophy teacher. As a political activist concerned with injustice, he had to mold his life and career in relation to the events, people, and issues that he encountered and cared about — which is another way of saying that this political artist worked exclusively with “found” material, whether it was Joseph McCarthy, the Kennedy assassination, various forms of leftist dissent, New York painters, Nixon, Hoover, or in the final analysis — and shortly before his death — himself. “I am the ultimate document,” de Antonio says in the film on two separate occasions, and chance as well as control have clearly played major roles in Hoover’s and his own compilations.

Cage, of course, is not the only exemplary figure cited by de Antonio, nor is his koan the only text, and it becomes much easier to grasp his significance in the film if one sees it as part of a larger mosaic or constellation. De Antonio also cites as models Pull My Daisy (a ground-breaking American independent short) and Cinda Firestone’s Attica, reads a powerful and influential statement by Jean-Paul Sartre (about man as an absolute value in his own time) that he first encountered in 1945, quotes Karl Jaspers on the subject of censorship (“Anything can be said as long as it signifies nothing”), and discusses the FBI’s enraged responses to Warhol’s Lonesome Cowboys.

De Antonio talks about Hoover’s victims — Ethel Rosenberg, Alger Hiss, Jean Seberg, and John Dillinger (as well as FBI agent Purvis, who gunned Dillinger down). He discusses Hoover’s cohorts — Clyde Colson, Joseph McCarthy, and Richard Nixon — and the fact that Cinda Firestone had fond personal memories of Hoover as a little girl. Also figuring in the discussion are all of his own major films and two media concoctions controlled by Hoover — his book Masters of Deceit, ghostwritten by many hands at a cost of a quarter of a million dollars, and a TV show called The F.B.I., which ran for nine years (de Antonio says 14) and which Hoover helped to produce.

8. “The film is not an attack on McCarthy,” de Antonio said of Point of Order in his 1978 interview with Rosenthal. “The film is an attack on the American government. My feeling is that if you look at the film carefully, Welch comes off as badly as McCarthy. He comes off as a rather brilliant, sinister, clever lawyer who used McCarthy’s techniques to destroy McCarthy. . . . Don’t misunderstand me. I wanted McCarthy gored to death but I also wanted the whole system to be exposed, and the only people who saw that were a few Marxists.”

By the same token, Mr. Hoover and I is not merely an attack on Hoover’s FBI but a statement of independence from all bureaucracies, governmental and otherwise. (De Antonio also gets in some licks against the CIA. In News From Afar, a fascinating short film made by Shu Lea Cheang just before de Antonio’s death, he seriously proposes — in the course of discussing recent events in eastern Europe, the Soviet Union, and Central America — that Bush abolish the CIA: “We don’t need the CIA any more than we need wings to fly.”)

A self-described anarchist, de Antonio believed most of all in the value of plain talk — in trusting his viewers not only to think, but to think for themselves. That is why he insisted on doing without narration in Point of Order — there was no need to explain what was happening and what the film’s relationship was to these events — and why he followed the same principle in In the Year of the Pig. Paradoxically, Mr. Hoover and I could be described from a certain point of view as consisting of little but narration — de Antonio telling us what he thinks. Yet the film is brave and lucid enough to be saying a lot more than what de Antonio is saying, and even doing more than he is doing. Its dialectical construction and de Antonio’s treatment of his own discourse as artistic “material” rather than as simple dogma liberate us as spectators, and compel us to engage with the film as we would with another person in a dialogue; the subject is not merely Hoover and de Antonio, but what they represent in relation to ourselves.

This is only one of the ways in which Mr. Hoover and I can be profitably compared to Roger and Me, a film that elicits a good deal less thought and reflection. (Significantly, de Antonio originally planned to call his film Mr. Hoover and Me, until he learned about the title that Michael Moore was giving to his film — a film, incidentally, of which he was highly critical.) It’s a pity that de Antonio’s film hasn’t been picked up by a major studio, or reviewed in Time or Newsweek or on any of the network TV shows, as Moore’s was, and that most people in this country will never even hear about it, much less see it. But at the same time, it isn’t very surprising, because the kind of integrity and power that de Antonio had as a filmmaker have almost nothing to do with the qualities that the media routinely reward. (Maybe if he’d lived another 20 years, he would have been inadvertently turned into an institution, as I.F. Stone was.) Fortunately, Mr. Hoover and I is as exciting and as lasting a legacy as anyone could wish; and it is there to be seen and learned from — for anyone who wants to encounter it.