From the Chicago Reader (April 19, 1991). — J.R.

JU DOU

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Zhang Yimou, in collaboration with Yang Fengliang

Written by Liu Heng

With Gong Li, Li Baotian, Li Wei, Zhang Yi, and Zheng Jian.

Like most people reading this, I know next to nothing about the history of China, which is thousands of years older than the U.S. and has a population over four times as large. In high school I was required to take courses in Alabama and American history; world history was an elective, but if that course had anything to do with China, I no longer recall any details. I also managed to get through seven years of college and graduate school without further edification on the subject.

I suspect that most people in China are comparably uninformed about the U.S. When my youngest brother was in Kenya in the late 60s, he spent time conversing with some Red Guard members who were stationed there, and used to have friendly arguments with them about where Coca-Cola, which they liked, came from; they were convinced it was a product of Kenya. It was difficult for them to accept that anything they liked came from the U.S., just as it’s difficult for many of us to accept that anything we like about China (e.g., the 1989 student protests in Tiananmen Square — routinely and misleadingly labeled prodemocracy in the American press) isn’t American in origin.

Given this tradition of shared ignorance, I think it’s less than useful to describe Ju Dou–a beautiful and disturbing new film from the People’s Republic of China — by comparing it to The Postman Always Rings Twice, as a good many American reviewers have done. Some of them have even had the brass to criticize the film for not living up to this comparison; “the postman barely rings once,” quips a blurb writer in the New Yorker, who goes on to criticize the stylization of one of the characters for recalling — and not living up to — a British SF programmer called Children of the Damned (1964). The implication is clear: it’s the business of Chinese filmmakers to study, emulate, and adhere to the standards and aesthetic principles set by Anglo-American pulp writers and hacks so that they can rise to the same cultural level as novelist James M. Cain and directors Tay Garnett and Anton Leader.

For the sake of argument, let’s concede for the moment that there are a few loose and superficial correspondences between Cain’s novel, Children of the Damned, and Ju Dou. Cain’s novel was written and set in the 30s, Ju Dou is set in the 20s — not the same decade, but we’re talking ballpark figures. Both stories center on a passionate adulterous affair between the wife and employee of a loutish boss in a rural area. But this is about as far as the comparison can go, and the only possible connection to Children of the Damned is the presence of a silent, threatening, and destructive child.

The problem with such comparisons is that they obscure considerably more than they clarify, by boiling down a story to what we already know and discarding or minimizing the rest. To give some idea of what is being discarded and minimized, a fairly detailed synopsis of Ju Dou is necessary (readers who’d prefer to see the film before hearing the whole story are invited to take their leave at any point). Considering that the film was recently nominated for an Academy Award (the first time a Chinese-language film has ever been nominated) and that the Chinese government, which has prevented the film from showing publicly in China, also tried unsuccessfully to have the nomination withdrawn, it’s important to try to understand not only what it means to us, but also what it means to — and for — China.

The beautiful Ju Dou (Gong Li) is the third wife of the owner of a dye factory named Yang Jinshan (Li Wei), a cruel, impotent tyrant who purchases her for the express purpose of fathering an heir; when he discovers that he’s incapable of impregnating her, he beats and tortures her. If we assume that such barbaric practices belong only to China’s past, the film’s director, Zhang Yimou, insists we’re wrong. “In remote rural areas among the peasantry,” he said in a recent interview, “you will still find far more serious cases of oppression than Ju Dou’s. Even today, you can buy a woman at the price of RMB 2000 to 3000 [approximately $400]. There’s no way the government can stop this. Sometimes the women escape, but if they are caught, they are chained, humiliated, and beaten in a very inhuman way.”

The employee in Ju Dou (Li Baotian) is an adopted nephew of Yang Jinshan named Yang Tianqing — unlike Ju Dou, he bears the family name of his uncle — who has been working for Jinshan for a long time before Ju Dou turns up. His affair with Ju Dou begins at her instigation and only after a certain amount of prodding; he was content to peek at her bathing herself through a hole in the wall. When she discovers that he’s been spying on her, her first response is to stuff the peep-hole with straw. Later, after Jinshan leaves on an overnight trip, she goes to Tianqing’s room and finds the door bolted. Only on the following day, after she confronts him (“Why are you afraid? . . . Do you think I’m a wolf? . . . I’ve kept my body for you”) and embraces him, do they finally make love.

Some time afterward, a doctor declares that Ju Dou is pregnant. Jinshan, believing that the child is his own, offers a grateful prayer to his ancestors, but Ju Dou whispers to Tianqing that the child is his. When the child is born, the elders in the village meet and one of them selects his name, Yang Tianbai (played by Zhang Yi as a child and Zheng Jian when he grows older). The affair between Ju Dou and Tianqing continues in secret during the baby’s infancy whenever Jinshan is away; she even offers Tianqing some of her breast milk. But when Jinshan’s donkey returns alone to the dye factory, Tianqing dutifully goes out looking for his boss; finding him unconscious, Tianqing carries him home on his back.

After the doctor announces that Jinshan is paralyzed from the waist down, Ju Dou and Tianqing become more open with him about their relationship, though the social front all three characters present to the village remains the same. After Ju Dou angrily tells Jinshan that Tianqing is the baby’s father, Jinshan tries to kill Tianbai. Another crucial difference between Tianqing and his counterpart in The Postman Always Rings Twice is then revealed: Tianqing is unwilling to murder his boss and uncle, despite Ju Dou’s expressed desire that he do so; the most he can do is threaten, “If you touch my son again, you’ll see what happens.”

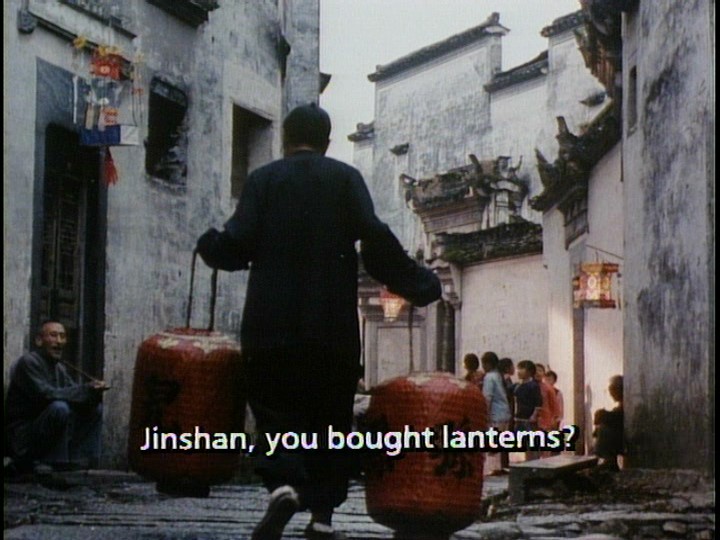

Jinshan responds to this crisis by trying to burn the dye factory down, but Tianqing and Ju Dou manage to extinguish the fire and then punish him by keeping him trapped in a bucket on wheels that they periodically hoist into the air with ropes, which causes him to pray to his ancestors for revenge. Some time later Tianbai plays with a cart while his parents sit on a hillside expressing concern about his failure to speak. “Anyway, he is your son,” Ju Dou says to Tianqing. “We’ll tell him when he’s older.” She goes on to say that her period is late and that she may be pregnant again. When Tianbai runs back home alone to the dye factory to dunk reeds he has gathered in a vat of dye, Jinshan moves behind him to drown him. But at a crucial moment the boy turns around and utters his first word to him: “Daddy.” Overjoyed, Jinshan embraces Tianbai. When Ju Dou and Tianqing return, he introduces them as “Mother” and “Brother.”

At a village gathering where Tianbai is toasted by the elders, Tianqing bursts into tears, and the locals comment that he’s drunk.

After Ju Dou painfully tries to abort a second child with chili powder and vinegar, and proposes fleeing the village with Tianbai, Tianqing replies, “If they knew, they’d kill us.” When she suggests poisoning Jinshan with arsenic, he takes umbrage: “How dare you — after all, he’s my uncle.” “And what am I to you?” she yells back. The doctor gives her medicine after she passes out, and we discover that her abortion was a success, though the doctor expresses some suspicion about how she became pregnant again.

One day while playing in the dye factory, Tianbai accidentally causes Jinshan to fall into a vat of red dye and drown; he laughs as the old man goes under. When Tianqing returns, he accuses Ju Dou of murdering her husband. When she sarcastically calls him a respectful nephew, he slaps her. “You’re beating me too?” she says. “Revive the old man and you can both beat me!”

Tianbai — who, it is clear by now, despises both his parents — is declared Jinshan’s sole heir by the village elders. There is gossip by now about the adulterous relationship, and the elders rule that Tianqing move out of the house and that Ju Dou be forbidden to remarry. The disgraced Ju Dou and Tianqing stand apart from the villagers during the funeral procession (whether this is because of their infidelity or traditional is not clear), though both of them make public displays of grief and even lie under the coffin as it’s being carried. Tianbai sits on top of it.

Seven or eight years pass. Tianqing visits Ju Dou and Tianbai with gifts for both of them, but the boy refuses to speak to him and rejects his gift. Ju Dou still wants to tell Tianbai that Tianqing is his father, and after Tianbai overhears some of the male villagers gossiping about Ju Dou and Tianqing, he rushes after one of them with a meat cleaver. Finally giving up the chase, but having bloodied his own hand with the cleaver, he returns to the dye factory, beats up Tianqing, and proceeds to wreck part of the factory. Ju Dou tells Tianbai that Tianqing is his father, but he only responds by locking him out of the factory.

Ju Dou and Tianqing meet again and go down to a cavelike cellar to make love; the lack of air in the chamber means that they will eventually suffocate, and they implicitly agree to a suicide pact. But Tianbai appears in the cellar, rescues Ju Dou, and murders Tianqing in the same vat of red dye in which Jinshan drowned. Grief stricken, Ju Dou takes a torch and burns the factory to the ground.

Perhaps the most curious aspect of Ju Dou, at least to a Western viewer, is the fact that all of the major adult characters are depicted realistically and Tianbai is not. When I asked a Chinese acquaintance about this after seeing the film for the first time, at the Toronto film festival last fall, he replied that the film was essentially about the inability of China to break away fully from its feudal past, and that Tianbai was the embodiment of this feudalism. (That print of Ju Dou, I should add, was saddled with ridiculous English subtitles, containing such expressions as “Make my day” and “What goes around, comes around”; it showed in that form — under the title Secret Love, Hidden Faces — at the Chicago Film Festival, where it won the top prize, the Silver Hugo; I’m happy to report that the film has been given new subtitles by its distributor, which has also restored its original Chinese title.)

I’ve given such a detailed synopsis to establish the links of the major characters with the village, which most American reviews I’ve read — as well as the synopsis provided by the distributor — have overlooked. Without this context, a comparison with The Postman Always Rings Twice might seem at least halfway viable; with it, such a comparison no longer seems relevant. Feudalism is a key concept in the history of China, but in an American context it has virtually no meaning at all. When Zhang Yimou remarks that Ju Dou’s relative slowness to rebel against her condition, as well as Tianqing’s sense of abasement and fidelity toward his uncle, “is the result of thousands of years of Confucian education” and a “lack of confidence in relation to one’s ego,” he’s alluding to a history and a social meaning that simply can’t be translated into American equivalents. Jinshan’s feudal ownership of Ju Dou and Tianqing and the dye factory, which is eventually inherited by his legal son, is accorded a social sanction that effectively makes any escape impossible. Even the fact that Tianbai is responsible for Jinshan’s death can’t break the chain of tradition that winds up crippling everyone, including Tianbai; his social and historical birthright ultimately overrides even his biological birthright, and the passion that produces him ultimately consumes him. The accidental death of his false father leads inexorably to the murder of his real father, just as Jinshan’s attempt to destroy the factory by fire is ultimately fulfilled by Ju Dou, the character who hates him and what he stands for the most.

The first film I ever saw from the People’s Republic of China was Li Wen-hua’s Breaking With Old Ideas (1975), a film about the building of a college for rural workers made during the last years of the Cultural Revolution. It can be rented on video here, but to the best of my knowledge it is no longer being shown in China. Indefatigably cheerful about creating a new social order that integrally involves the peasants, strictly realistic in style, and both frontal and symmetrical in framing, this film seems a world apart from the “fifth generation” films that emerged from China in the 80s — films such as Tian Zhuangzhuang’s The Horse Thief, Huang Jianxin’s The Black Cannon Incident, Zhang Junzhao’s One and Eight, Wu Tianming’s Old Well, Chen Kaige’s Yellow Earth, and Zhang Yimou’s only previous feature, Red Sorghum.

The directors of these films were in their teens during the Cultural Revolution, and when they enrolled in the Beijing Film Academy — the only film school in China — they were all adults with a decade of postrevolutionary experience behind them. They were also the first contemporary generation of Chinese filmmakers exposed to Western films, and the films they directed show traces of this exposure in a way that Breaking With Old Ideas clearly doesn’t. They remain our major pipeline into contemporary Chinese cinema, but it’s important to bear in mind that some of their best-known films in the West are not necessarily well-known in China. (The Horse Thief, for example, got very limited domestic exposure; Ju Dou has had no mass exposure at all, and has been seen only at a few private screenings and on unofficially circulated video copies.)

The Western influences on these films shouldn’t mislead us into taking them as would-be Western artifacts. It’s even questionable whether the Western practice (and auteurist implication) of assigning a possessive credit to directors, which I’ve followed here, is fully appropriate; none of these directors is credited with his own script, for instance. Zhang Yimou may well be the most versatile member of the group — he was the cinematographer on One and Eight, Yellow Earth, and Old Well, in which he also acted — but on Ju Dou he is credited with a codirector, Yang Fengliang, and the script of the film, while apparently written under Zhang’s supervision, is by Liu Heng, the author of the contemporary novella Fu Xi, Fu Xi, which Ju Dou is based on. Moreover, from the little I know about the novella, the film is far from a simple, straightforward adaptation. The action of Fu Xi, Fu Xi takes place between the 1920s and the 1970s (according to Zhang, keeping all of the film’s action in the 20s made it easier to get the script approved), and the adulterous couple in the original are a brother and sister.

Some commentators have suggested that Ju Dou is being suppressed in China because of its erotic content, and I must admit that the film is more sexually explicit than any other film from the People’s Republic I’ve seen. But its pessimism about the feudal past may be an even more relevant factor. The film — which was financed by the Japanese production company Tokuma and used Japanese equipment, but was made with an all-Chinese crew — went into preproduction before the Tiananmen Square crackdown. When the crew was reorganized two months later, the budget had been reduced by a third. Certainly the government crackdown can be interpreted as a feudal throwback of sorts, so it seems possible that the story could be interpreted along similar lines: insofar as Tianbai represents “the return of the repressed,” his brutality and lack of forgiveness can easily be associated with the Chinese government’s punitive responses.

Visually stunning, with ravishing uses of color and beautifully modulated lap dissolves, Ju Dou may not be the most formally striking Chinese film I’ve seen — I still prefer The Horse Thief, which I’m happy to say has recently become available on video — but it certainly is the most effective and dramatic in terms of commercial moviemaking, both as spectacle and as story telling. The film is organized around recurrences and rhyme schemes involving both colors (of fabrics and dye vats) and architecture (with the wooden steps leading from the factory up to Jinshan’s bedchamber serving as a pivotal site). The buildings used date back to the Ming dynasty (1368-1644), and probably for this reason suggest the feudal period even more than the characters and village customs do. A passionate tragedy with a contemporary social message, Ju Dou can only be understood if we step beyond the confines of our own historical context and think about a culture where even the contemporary spans centuries.