This ran in the May 1, 1992 issue of Chicago Reader. Criterion brought out a new Blu-Ray edition of this film yesterday, with many extras, so I’ve just looked at it again, and enjoyed it somewhat better this time, particularly for its pacing. My piece strikes me now as unduly peevish in spots, in part because I was reviewing the hype as much as the movie (I especially regret my swipe at Terrence Rafferty), although I still agree with much of it — and am pleased that Sam Wasson’s essay for the Criterion release agrees with one of my major arguments when he writes, “Far from making the trenchant, bitter satire so many critics would describe even after they saw the movie, Altman bypassed The Day of the Locust for Our Town and actually made a charmed, even gleeful movie about his so-called nemesis. That’s why so many people in Hollywood love The Player.” — J.R.

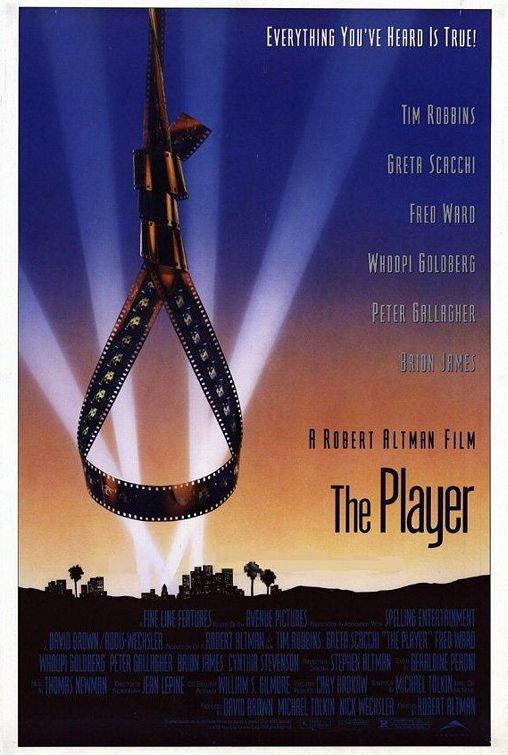

THE PLAYER

* (Has redeeming facet)

Directed by Robert Altman

Written by Michael Tolkin

With Tim Robbins, Greta Scacchi, Fred Ward, Whoopi Goldberg, Peter Gallagher, Brion James, Cynthia Stevenson, and Dean Stockwell.

Movies-about-moviemaking tend to come in two flavors: the celebratory (Day for Night, Singin’ in the Rain) and the sardonic (Sunset Boulevard, The Bad and the Beautiful, Barton Fink). But The Player skips blithely beyond both categories to something far richer and stranger — something at once antic and metaphysical. . . . The Player is about how the industry crushes the originality out of anyone who participates in it — any Player, be he writer, director, or production chief. — Stephen Schiff, Vanity Fair

A Martian reading the above might conclude that neither Robert Altman nor Stephen Schiff participates in “the industry.” Consequently, the Martian might think, neither do The Player or Vanity Fair. So I guess that when a press junket was held for The Player last month in Manhattan (to be fair, a few weeks after Schiff filed his story) — journalists were flown in gratis and treated to fancy hotel rooms and meals so they could interview some of the prime “players” involved in The Player and write or tape original, scathing, and uncorrupted accounts of how original, scathing, and uncorrupted The Player is — clearly, none of the journalists or publicists involved in it had anything to do with the industry either.

A savvier Martian might say that all these kibitzers are players just like the characters in Altman’s movie, arguing that spectators who groove on the players’ inside dope automatically join the club too. The only apparent difference is that the players in the movie are all corrupt assholes who literally get away with murder and wouldn’t recognize a good movie if it bit them, while the players in the audience are all seekers after truth who recognize it the instant they see it. Originality may have been routinely crushed out of the makers of Singin’ in the Rain, Sunset Boulevard, The Bad and the Beautiful, and their hapless successors, but richer and stranger observers of the antic and the metaphysical — that is, Altman, Schiff, and other hip individuals who think exactly like them — belong to a higher breed and a different profession entirely.

Speaking now from an earthling’s vantage point, the problem with Schiff writing such hype about The Player is not very different from the problem of Altman — or any other commercial director — making such a movie in the first place. That is, how does the pot establish its special, expert credentials for calling the kettle black? It’s not clear to me that the entertainment value of The Player is much different from the entertainment value of Oscar night; both are full of star spotting, sardonic gibes about venality and designer mineral water, glitzy put-downs of glitz, and so on. If Billy Crystal suddenly turned up as one of the walk-ons in The Player, complete with one of his ready quips as emcee, he wouldn’t really be out of place. In a way, all arts journalists (myself included) are unavoidably part of the industry insofar as they become part of the publicity. The surreal aspect of Schiff’s statements is that they imply we all belong to a more exalted profession.

***

To its credit, The Player seems to have a pretty authentic feel — judging from my own limited experience — for what a contemporary story conference and studio lunch is like. If simple observation of such rituals were all the movie had on its mind, I’d have fewer problems with it. But Michael Tolkin’s screenplay — and presumably his own novel, which he adapted — is also tricked out with a bogus noir thriller plot full of red herrings and a boringly conventional love story that includes the least interesting character I’ve ever seen Greta Scacchi play. In terms of mise en scène, we get a show-offy opening shot and some equally show-offy extreme close-ups near the end but, contrary to what we’ve been hearing, no particular signs of development or renewal in Altman’s camera style. The music is a banal new-age score by Thomas Newman that seems to favor strings, percussion, and what sound like wind chimes; whether we’re supposed to take it straight or as a comment on soulless yuppies is never firmly established.

Tim Robbins does a nice job of logging some of the class attitudes and behavioral patterns of studio executives. As Griffin Mill, a senior vice president in charge of production at a studio whose slogan is “Movies . . . now more than ever!”, he shows not only the imperturbable surface of such an individual but also his character’s growing nervousness about both another young executive who might replace him and a stream of threatening hate mail he’s been getting from an anonymous screenwriter whom he clearly never “got back” to. Focusing on one of the writers he thinks might be responsible for the letters, Mill drives out to Pasadena, flirts with the fellow’s girlfriend over his cellular phone, tracks the writer down in an art theater, and later, after an argument in a karaoke bar, ends up killing him.

Unfortunately, Mill is interesting only as an index of how studios work. We don’t even care that we never see what the inside of his house looks like, and the movie’s remaining characters — apart from a few profiles of other studio personnel, who serve comparably schematic functions — are so thinly imagined that they’re uninventive even as cartoons.

I suppose it could be argued that the characters in Altman’s The Long Goodbye are also thin and cartoony. But the distance between, say, Mark Rydell’s sublime caricature of a Jewish gangster in the earlier movie [see photo above] expounding his guilt for having gratuitously smashed his girlfriend’s nose with a Coke bottle and Whoopi Goldberg’s Pasadena cop in The Player twirling a tampon around her finger while she interrogates Mill is, quite simply, astronomical. The first character has the benefit of not only Leigh Brackett’s dialogue but also Rydell’s manic-demonic intensity; the second has the flattest dialogue imaginable and the simple shock value of Goldberg saying “fuck” and referring repeatedly to tampons. Rydell’s Marty Augustine is a fully formed expressionist portrait that radiates weirdly in all directions; Goldberg’s Detective Avery arguably isn’t even a character, just a joke dressed up with shtick.

The Player has a moralistic bee in its bonnet about the horrible ways Hollywood screenwriters are treated by studio executives. While this obviously has some solid basis in fact, it’s also self-serving on Tolkin’s part and inadequately imagined in terms of the characters and story. To my mind, the only scene that deals with this subject directly, a pivotal one in terms of the plot, is the first scene that rings wholly false. It’s a conversation set in a Pasadena karaoke bar between Mill and the disgruntled screenwriter (Vincent D’Onofrio), and unless you’ve put your brain on the kind of automatic pilot that TV reruns require, not a moment of this scene is believable. (The second false scene, which has equally stale, flabby dialogue, deals with the same screenwriter’s funeral.)

The falsity of these scenes grows in part out of a notion of Hollywood creativity that strikes me as being somewhere between 20 and 40 years out of date — 40 years if you date it back to the screenwriter hero in Sunset Boulevard (who is explicitly mentioned at one point in The Player), 20 years if you trace it to the publication of Pauline Kael’s essay “Raising Kane.” Kael’s essay argued that the true unsung genius of Citizen Kane was its cowriter, Herman J. Mankiewicz, and strongly implied that Orson Welles, credited as cowriter, didn’t write a single word of the script and actively plotted to deny Mankiewicz any screen credit. The first of these implications was conclusively shot down by scholars and the second has never been substantiated, but the mythic power of the noble, suffering screenwriter and the snappy assertiveness of Kael’s prose were strong enough to drill these dubious notions into many impressionable skulls.

An even more important early-70s source for The Player, as pointed out to me by my friend and colleague Bill Krohn, is an article by Joan Didion, one of Kael’s detractors, that was published first under the title “Having Fun” in the New York Review of Books and then as “In Hollywood” in The White Album. Didion’s essay — which has more to do with The Player‘s image of the industry as a whole than of screenwriters in particular — leads off with a quote from Fitzgerald’s The Last Tycoon (which, like The Player, has a studio executive as hero) and tweaks the naivete of film critics like Kael, Stanley Kauffmann, and John Simon about how things actually work in Hollywood. In this essay Didion practically invented the notion of hip literary knowingness — “infotainment” for intellectuals — on such subjects as how “points” on pictures are calculated, how the man who does her hair has his own movie story to pitch, and how “the average daily narcotic intake” of a certain “level of ‘young’ Hollywood . . . is one glass of a three-dollar Mondavi white and two marijuana cigarettes shared by six people.”

Evoking swank dinner parties where the guests “settle down to The Heartbreak Kid with a little seltzer in a Baccarat glass,” Didion was identifying herself as a savvy “player” in the Hollywood deal-making game she was describing and inviting her readers to alternately cluck their tongues and drool over her shoulder at all the cynical goings-on in lotusland. The Player extends a similar “exclusive” invitation into the industry’s inner workings, but two decades later such invitations have become part of an entire cottage industry.

Some of the cherished pre-Didion notions still persist, however. One of these is that Hollywood screenwriters are all pure artistic souls brutalized by unfeeling producers, when it seems to me that these writers often deserve the treatment they get (or don’t get) in the same way that writers who write infotainment pieces for a dollar a word in Premiere do. Based on the professional screenwriters I’ve known, most of whom devote their lives to making comfortable livings off of scripts that never get filmed, I’d hazard the opinion that, as a group, they’re not intrinsically more serious or ethical than directors, stars, producers, or anyone else in the industry. The best writers, like Faulkner, were never seriously damaged by their screenwriting gigs, and most of the Algonquin wags like Mankiewicz probably wound up getting more attention and fame than they would have otherwise. The only script ideas or screenplay extracts we hear in The Player are banal and stupid, bad even on a parodic level; if Tolkin and Altman are arguing, like Schiff, that these are gifted artists having their originality crushed out of them, they sure aren’t bothering to give us any evidence of this originality.

They are implying that almost everybody involved in setting up a movie is a hypocrite. So what else is new? The ultimate “truth” of The Player comes in several stages of trite revelations that the press material asks reviewers not to give away. (People who cherish these minor surprises — and the threadbare plot of The Player, alas, has little else to offer — may want to stop reading here.) One of these revelations is that when Habeas Corpus, a fatuous script idea pitched by an English filmmaker (Richard E. Grant) and American producer (Dean Stockwell), actually gets filmed, the filmmakers’ original insistence that no stars or happy ending be used turns out to be the purest hypocrisy: there are loads of stars and a happy ending, and they’re as pleased as punch.

“What about truth? What about reality?” shrieks Bonnie (Cynthia Stevenson), a script editor and former girlfriend of Mill, about this profound “sellout,” and she promptly gets fired for her candor. If I were running the studio I’d consider firing her too: the thrust of her complaint is that this silly pastiche of a movie would have been great, or at least serious, if it hadn’t had any stars or it had had an unhappy ending, and on the basis of what we see and hear (including the happy ending) this notion is plainly idiotic. But to convince us that what’s been done to Bonnie is unjust, the movie proceeds to put her through such further humiliations as breaking a heel and being snubbed by Mill as he walks to his car, so that we last see her sobbing disconsolately in the parking lot. Presumably we’re so cynical by this time that we’re meant to chortle over her misery.

Undercutting this whole business is the fact that what we see of Habeas Corpus doesn’t even look like a crass Hollywood movie. Altman hasn’t even bothered to make the camera style used in it (telephoto lens with a slow backward zoom, if I’m not mistaken) any different from his own. “Aha!” I can imagine a defender of The Player saying. “That’s just the point! Altman’s saying he’s really no different from anyone else in Hollywood!” And maybe the defender would be right. It still doesn’t make The Player especially insightful. The ultimate, earth-shaking lesson of both The Player and its reception in the press remains how hip we all are to Hollywood hypocrisy.

To judge from the unending torrents of gush that have been pouring out of mainstream reviewers, you’d think this movie might at least qualify as Altman’s triumphant comeback. The problem is, considering how uneven his oeuvre is, comeback from what and to what? It’s important to try to distinguish hyperbole about “classics” from the hard question of what of Altman’s work actually remains meaningful or vital. What makes it especially hard to do this is that Altman’s best films — which I take to be McCabe and Mrs. Miller, The Long Goodbye, and Nashville — are effectively unavailable today in their original ‘Scope formats. (The first and last of these can be seen on video only in scanned versions, with reediting and reframing that eliminates about a third of the image; the second isn’t available on video at all.)

If I were to trust the responses I had in the 70s to Altman’s work, they would suggest that his talents as an instinctive director were quickly jeopardized by the immoderate praise that some critics heaped on his “ideas,” which were seldom as good or as reliable as his sense of style but which became increasingly prominent after Pauline Kael seriously compared him to James Joyce and William Faulkner (in two separate reviews, no less). In McCabe and Mrs. Miller (1971) and The Long Goodbye (1973), his elected genres (western and detective story), settings, source novels, screenwriters, and actors only enhanced his highly original uses of camera movement, music, and overlapping dialogue. Both movies had a sense of stylistic and syntactical drift that remained remarkably potent in the various ways it solicited and rewarded viewers’ imaginations; the encounters of music and image in the first and the continuous camera movements in the second offered the pleasures of formal beauty and abstraction as well as dreamy, open-ended commentaries on what the films were about. But in Nashville (1975), a certain debilitating hubris was already beginning to take over in spite of the film’s virtuoso narrative design. Nothing less than a cliched notion of “America” itself wound up curtailing the stylistic openness and converting many of the resulting abstractions into shallow conceits. If Nashville begins by shooting its two dozen characters off into diverse and disparate directions, it ends by pooling them all into a single corny concept represented by repeated shots of the American flag — a reduction of the material rather than an expansion of it, and a move that only underlines how little interest the filmmakers actually have in Nashville or country music or politics, except as ready-made state-of-the-union fodder.

From there, it was only a regressive hop, skip, and jump for Altman into mannerism and still loftier themes, as he showed in Three Women (1977). The emotional complexity of Nashville eventually gave way to the relatively empty cartoon pyrotechnics of A Wedding (1978) and Popeye (1980), while the experiments with overlapping dialogue that peaked around the time of California Split (1974) were abandoned for the sake of portentous sermons (Buffalo Bill and the Indians and Quintet), snide collections of jokes (the limited releases Health and O.C. and Stiggs), and the glib exercise Secret Honor, which somehow contrived to be both.

The Player is portentous and snide, too, but for once Altman has hit on a subject that his audience enjoys feeling portentous and snide about — the Hollywood that we all take so seriously, with our daily fixes of infotainment, but feel uneasy about supporting uncritically. Beginning and ending with a framing device borrowed from Nashville — in which the movie we’re watching is acknowledged as a manufactured and packaged consumer product — The Player makes it clear fairly early on that it doesn’t have to show much inventiveness in order to score; all it has to do, really, is to make the right gestures. If it emphasizes through framing that it’s playing on our voyeuristic desires — the hero and heroine are mainly introduced through windows that we “surreptitiously” peek through — every other directorial choice becomes secondary. If we’re made to “overhear” various muttered insults in restaurants and at parties, it doesn’t matter that Altman doesn’t give us choices about which comments to give more weight to or that the dialogue we hear is strictly standard issue (Burt Reynolds muttering “asshole” after he greets Griffin Mill). The Player not only lets us have our cake and eat it too — that is, both ogle and feel superior to all the hot tubs and mud baths — but it also purports to be instructing us, just like Premiere and Entertainment Tonight. This is how bad movies get made, it is telling us. This is what players do.

***

The Player has the exhilarating nonchalance of Altman’s 70s classics, and its tone is volatile, elusive. With breathtaking assurance, the movie veers from psychological-thriller suspense to goofball comedy to icy satire: it’s Patricia Highsmith meets Monty Python meets Nathanael West. — Terrence Rafferty, New Yorker

I assume that Rafferty has temporarily forgotten that Nathanael West’s Hollywood novel The Day of the Locust is about misfits and failures who exist outside the studios — industry nobodies, most of whom could never even reach Griffin Mill on the phone, much less be told “I’ll get back to you.” During various portions of The Player‘s first and best shot — an eight-minute take that deceptively promises some of the narrative complexity of Nashville — we hear a series of people pitching script ideas to Mill, and it’s a running gag that they’re all basing their pitches on combinations or derivations of earlier hits: Buck Henry pitching The Graduate,”part two,” Alan Rudolph pitching The Manchurian Candidate meets Ghost, and so on.

These silly pitches invite our derisive laughter. Rafferty’s expression “Patricia Highsmith meets Monty Python meets Nathanael West,” on the other hand, is supposed to be discourse of a different order. As prose, I guess you could say it’s Pauline Kael meets Michael Sragow meets Stephen Schiff meets Robert Altman meets Hollywood and simply leave it at that.