From the Chicago Reader (September 25, 1992). — J.R.

BOB ROBERTS

*** (A must-see)

Directed and written by Tim Robbins

With Robbins, Giancarlo Esposito, Ray Wise, Gore Vidal, Alan Rickman, Bob Balaban, John Cusack, Susan Sarandon, Peter Gallagher, James Spader, and Fred Ward.

With Unforgiven unexpectedly topping the box office charts and Bush bashing so popular now that even my favorite comic book, USA Today, seems to do it daily, this appears to be the season of demystification. But I wonder how far the public is prepared to take this process. Since it premiered at the Cannes film festival four months ago, I’ve been looking forward to Tim Robbins’s directorial debut, described as an unbridled attack on the Republican glibness and greed of the past dozen years. Clearly the climate is ripe for some good old-fashioned muckraking. But how much of this involves a genuine change in national perception, and how much is it a merely seasonal media construction? As pleased as I am at the media’s apparent recognition of some of Bush’s crimes, it’s hard for me to understand how this squares with the media’s former position that these crimes never took place (as with Iran-contra) or didn’t matter (as with the savings-and-loan scandal) or were heroic deeds showing both restraint and maturity (as with the slaughter in the Persian Gulf). It’s like squaring the public perception of Twin Peaks the miniseries in the spring of 1990 with that of Twin Peaks the movie in the autumn of 1992: the series was the hottest thing on TV, of vital interest to everyone; the movie was the biggest late-summer flop, of almost no interest to anyone. Of course one could argue that the original Twin Peaks pilot was worthy of Luis Bunuel and the new movie isn’t even up to minor Clive Barker — just as one could easily stipulate that Bush went from being Winston Churchill in the spring of 1991 to Gerald Ford five seasons later — but I would argue that the difference between the old and new models in each case is a lot less pronounced than most people claim.

In the final analysis, what we may need the most in such matters is neither rubber stamping nor mechanical dismissal but something in between — understanding, not attitudinizing. Bob Roberts is currently being heralded as a mechanical dismissal of a certain kind of rubber-stamping that helps us all to attitudinize to our heart’s content, but personally, I’d rather celebrate it for what it does for our understanding. Which is a lot.

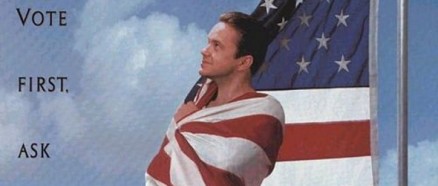

“Responsible journalism is objective,” declares Bob Roberts (Tim Robbins), a slick, wealthy 35-year-old conservative campaigning across Pennsylvania in the fall of 1990 (shortly before the war in the Persian Gulf) for a seat in the U.S. Senate. “This is a national security state,” remarks Brickley Paiste (Gore Vidal), the old-fashioned 66-year-old liberal incumbent Roberts is trying to unseat. “If you want the truth in this country, you have to seek it out,” says Bugs Raplin (Giancarlo Esposito), a paranoid but perceptive journalist bent on exposing Roberts’s part in a scam that involved both S and Ls and drug running. But for those who want the truth, objective or otherwise, about the stunning if uneven Bob Roberts, it’s worth recalling F. Scott Fitzgerald’s observation that the test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposing ideas in one’s mind and still be able to function.

As I see it, the real news about this movie is that Robbins as a writer-director has a first-rate intelligence as a satirist, which means that even though Bob Roberts consists of nothing but sound bites, Robbins himself doesn’t think in sound bites. To hear most reviewers tell it, Robbins’s satirical intelligence goes no deeper than the Bush bashing that has become so fashionable recently, and while I wouldn’t want to deny that this movie makes some devastating and hilarious observations about the moral legacies of Reagan, Bush, and Quayle, it differs substantially from the media’s treatment of the current presidential campaign in that it refuses to postulate a substitute hero. And unlike the media it is brutally but more or less accurately describing, it never resorts to being cynical, defeatist, or opportunistic. (Though one of the most comic elements in the movie is the songs sung by Roberts, a folksinging conservative. Robbins has refused to issue a sound track album so the songs can’t be appropriated by the right.)

Bob Roberts takes the form of a documentary being made about Roberts’s campaign in the fall of 1990 by a British filmmaker (Brian Murray), and because the media control such campaigns, the media are essentially the subject of every scene. (The movie is especially impressive for the mastery with which it apes the documentary form.) Not only does the movie lack a hero or a villain in any conventional sense; it can’t be said to have any characters at all — only images and sound bites. Yet it never seems thin or undernourished. On the contrary, the movie’s major flaw — a common one with ambitious first features — is that it tries to cram in far too much. (A visit to the Jefferson Memorial in Washington, D.C., toward the end provides the only moment that borders on fatuousness.)

Many of the concepts in this movie can be traced to Robert Altman, Robbins’s mentor — particularly to Nashville, Tanner ’88 (Altman’s HBO miniseries), and The Player. But Robbins’s uses of Altman’s conceptual ideas are so much more analytical that they never come across as potshots. Altman satirizes behavior, while Robbins views it within the larger framework of media discourse. A basic rule of thumb about the three Altman movies cited above, in their uses of songs (Nashville), political campaigns (Nashville and Tanner ’88), and star cameos (all three), is that practically every character comes across as silly or stupid at one point or another; everyone and everything is fair game. This is plainly not the case in Bob Roberts, where most of the statements made by Brickley Paiste and many of those made by Bugs Raplin clearly carry Robbins’s approval and endorsement.

Why then, one may ask, do Paiste and Raplin fail to come across as heroes? Because Robbins is concerned with discourse — images and media configurations — not with characters. (Even the names of these figures suggest that they’re not to be taken seriously.) The rather pasty Brickley Paiste looks stuffy and his oratory sounds old-fashioned; the somewhat bughouse Bugs Raplin looks slightly mad whenever he’s seen in close-up. This is where Fitzgerald’s definition of a first-rate intelligence comes in. In short, the camera-and-microphone identities of these figures exist independently of the truth of their words, with the disquieting result that nothing either man says ever comes across as completely “believable.” Bob Roberts, on the other hand, because he’s created his own image for the media, can lie as often as he pleases and appear genuine and persuasive. He can even appropriate the rhetoric and trappings of populist folksingers and subvert them for yuppie purposes.

In other words, Bob Roberts is as much a critique of the styles of Bill Clinton and Albert Gore — even though it was written and filmed well before these men became the Democratic front-runners — as it is of the political substance of Ronald Reagan, George Bush, and Dan Quayle. Ultimately one could say that the movie is about the degree to which personal style transforms political substance — even effectively eliminates it from public consciousness. Indeed, insofar as the media and their limited repertoire of political themes and concerns dictate the terms of a campaign even more than the candidates do, Bob Roberts is not so much prescient about the current campaign as perceptive about what was already happening in 1990 and 1991.

It might be argued that a right-wing politician who goes around singing ersatz folk songs is not entirely convincing. Maybe not, but it’s close enough to an extrapolation of the present interface between politics and show business to make the film’s treatment of that interfacing extremely suggestive. (Sex scandals and political assassinations as show-biz phenomena are among the subjects considered.)

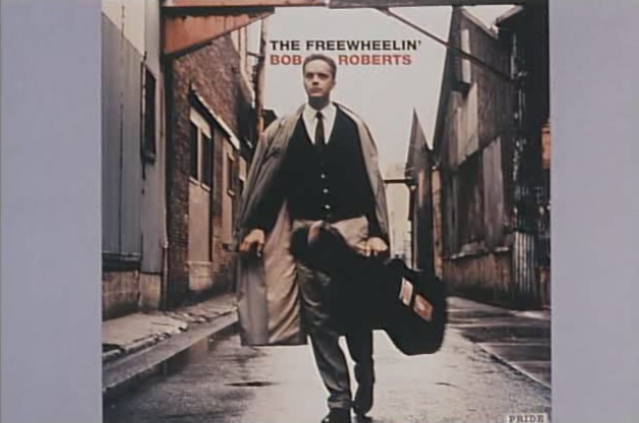

Robbins started to write his script in 1986, and, significantly, the title character started out as a businessman-singer rather than a political candidate — although, Robbins has said, “the media circus and the emphasis on telegenics were always there.” Later, Robbins made a short film about the character for Saturday Night Live, though interestingly enough one of the deadliest parodies in this movie is of Saturday Night Live itself. Like Roberts’s folk songs and music videos, the show is seen as an antiestablishment envelope packaging conformist goods. The funniest demonstration of this principle is Roberts’s “Wall Street Rap” video, which highlights the key words on title cards — a technique derived from Bob Dylan’s illustration of “Subterranean Homesick Blues” in the music documentary Don’t Look Back — while dancing girls wearing ties and hot pants celebrate yuppie pride in an alley behind him. (The jump cuts between the title cards held by Roberts and dancing-girl configurations behind him are a beautiful example of the kind of mental abbreviations that his media style both consists of and engenders.)

Though Gore Vidal’s age and manner suggest Bush rather than Clinton and Tim Robbins’s age and manner suggest Clinton and Gore as well as Quayle, the movie functions nonetheless as a detailed commentary on the presidential campaign; in fact, the crossovers complicate and extend the terms of the analysis. A veritable anthology of various media abuses, the movie can only enhance and sharpen our understanding of what’s going on.

A good many of these commentaries belong to the actors, Robbins himself most of all. When Fred Ward as a newscaster laughs about being unable to read a statistic about the homeless off a prompt card, this cold-blooded lightheartedness is only one example of a familiar TV stance being etched into our minds with acid. (Other newscasters are played by Susan Sarandon and James Spader, among others, and it’s worth noting that these and other well-known actors are never called upon to play themselves like the stars doing cameo turns in The Player; each has his or her own actorly points to make about what might be called the behavioral ethics of anchorpeople, and these points are made with wonderful wit and intelligence. Much the same could be said for John Cusack and Bob Balaban and their respective roles in the Saturday Night Live parody.)

While the smart-ass attitudes in Altman comedies can sometimes be read as celebrations of stupidity, Bob Roberts is much too angry a satire to lend itself to such complacency. But this doesn’t prevent it from being enormously liberating and insightful — a catalog of not only the worst political abuses and hypocrisies in American politics over the past decade, but some of the worst kinds of behavior in the electorate as well. (The suffering faces of some of Roberts’s fans after their hero is apparently martyred is alone worth the price of admission.) While it’s a given in both campaign rhetoric and TV reporting that anyone can be charged with stupidity except the American people who voted the clowns into office in the first place, Robbins isn’t quite so accommodating about letting us off the hook. After treating us to countless pseudo folk songs, all of them hilarious, he concludes with a genuine folk song — Woody Guthrie’s “I’ve Got to Know” — over the final credits, followed by an injunction in the form of a title: “Vote.” It’s a tribute to this very funny movie that when this word appears at the end its meaning is made to seem complex, not simple.