The degree to which contemporary cinema has become a desperate recycling operation was pain fully evident in Berlin this year, where even the better films seemed mired in familiar habits. Aki Kaurismaki’s Ariel, a hard-luck story of an unemployed miner pushed into a life of crime, is basically a Warners B-film of the 1930s, cleanly told and decked out with a few 80s ironies, but really nothing new. Martin Donovan’s Apartment Zero, a baroque male-bonding thriller set in Buenos Aires, superbly acted by Colin Firth and Hart Bochner, offers a chilling and complex view of the American abroad, yet its precise genre positionings would be unthinkable without its cues from Hitchcock, Chabrol and Polanski.

For many colleagues, a major disappointment in the competition was Chantal Akerman’s first English-language feature, Food, Family and Philosophy in French (or Histoires d’Amérique in French), a string of monologues and jokes by Jewish immigrants, delivered against Brooklyn exteriors within hailing distance of the Manhattan skyline over what appears to be a single night. The uneven text and performances which are addressed by the actors more to the camera than to each other are major stumbling blocks. Yet the film still seems, for better and for worse, a logical successor to Akerman’s Toute une nuit (an insomniac’s night of interweaving mini-plots) and Golden Eighties (a grim deployment of show-biz staples within an eerily confined universe), with an equally melancholy aftertaste. Even without the neurotic intensity and painterly precision of Akerman’s best work, the singular poignance of her dark world remains.

Even more of an anthology effort is Jacques Rivette’s 165-minute La Bande des quatre (The Gang of Four), immaculately constructed and executed and with a plot which seems to contain elements of almost every previous Rivette feature. The theatre collective this time is an all-female acting school run by Bulle Ogier, and the mainly offscreen complot involves a group of crooks and/or cops — as one of the young actresses notes, it doesn’t matter which — whose aggressive and seductive machinations threaten to break up the collective.

The dialectic between female cameraderie and se, and between collectivity and competition, as mutually exclusive ensnarements is as pronounced here as in Céline et Julie vont en bateau and L’Amour par terre, and Rivette’s recent predilection for young actors bears more fruit here than it did in Hurlevent. One misses the spirit of adventure and experiment that galvanised all his work between L’Amour fou and Noroît, but this is still probably his most accomplished feature since Le Pont du Nord, with a dramatic payoff which more than justifies the characteristically slow build-up.

Outside the competition, the most interesting works tended to be mainly archival in one way or another. Harun Farocki’s Images of the World and the Inscription of War, a thoughtful and provocative essay film about photographic records of Auschwitz; Charlotte Zwerin’s Thelonious Monk: Straight, No Chaser, a conventional jazz documentary made exceptional by the wonderful Christian Blackwood footage from the 1960s of Monk at work which makes up its bulk; and a fascinating presentation of the short, quirky films of Belgian artist Marcel Broodthaers.

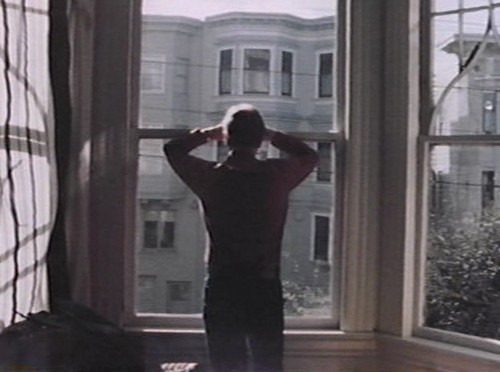

The two most original new films I saw were both low-budget independent productions. Jon Jost’s Rembrandt Laughing, which follows a group of friends over several mainly uneventful days in San Francisco, and István Dárday and Györgyu Szalai’s The Documentator. Working once again with improvising actors, Jost exhibits a warmth in dealing with flaky West Coast characters -– who include a sand collector, a picture framer, a couple of architects and a bailbondsman –- that allows their personalities, moods and interactions to register even when he is filming them obliquely and elliptically, which is often.

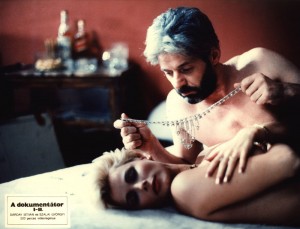

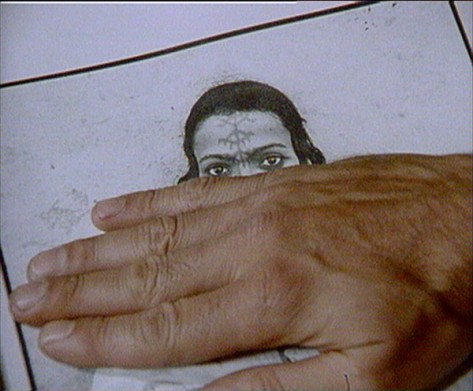

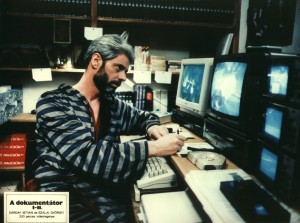

A Dokumentátor has a running timeof 215 minutes, but not the least of its singular virtues is the fact that one can never predict where it’s going. A good half of the film consists of video material of every conceivable kind (newsreel and archive footage, porn, TV commercials, clips from features)which is the owner of a video rental store is amassing and watching in the sealed-off universe of his shop and the apartment that he shares with his beautiful girlfriend. She, meanwhile, is becoming involved with his young clerk (nicknamed ‘Rambo’). A grimly satirical commentary on the all-encompassing qualities of video and on Hungarian consumerism, this is a film that certainly bides its time, but steadily grows in interest all the while.

JONATHAN ROSENBAUM