From the Chicago Reader (June 28, 1996). This essay subsequently grew into a book, commissioned by Rob White for the BFI Modern Classics, that came out in 2000, proved to be one of my most popular, and went into a second edition; a French edition is also available (2005), translated by Louis Malle’s daughter Justine, as well as a Czech edition and even an unauthorized Farsi one. — J.R.

Dead Man

Rating **** Masterpiece

Directed and written

by Jim Jarmusch

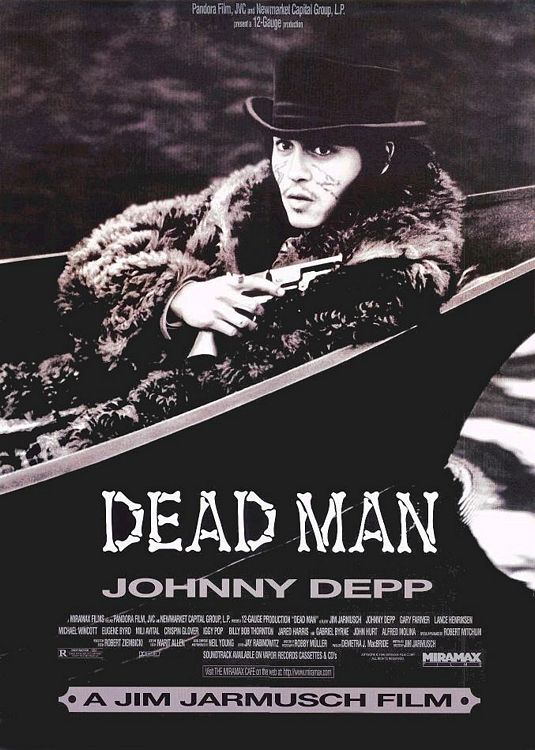

With Johnny Depp, Gary Farmer, Lance Henriksen, Michael Wincott, Eugene Byrd, Mili Avital, Gabriel Byrne, John Hurt, Iggy Pop, Billy Bob Thornton, Jared Harris, Jimmie Ray Weeks, Mark Bringelson, Michelle Thrush, Alfred Molina, Robert Mitchum, and Crispin Glover.

When we speak of “seriousness” in fiction ultimately we are talking about an attitude toward death. — Thomas Pynchon

Jim Jarmusch’s Dead Man, a disturbing, mysterious black-and-white western, opens with someone named William Blake (Johnny Depp), a recently orphaned accountant from Cleveland, traveling west on a train with the promise of a job at a metal works in a town called Machine. He keeps dozing off and waking to new sets of fellow passengers, including several who fire their guns out the windows at a herd of buffalo. (Such occurrences were common in the 1870s, encouraged by the government as a means of wiping out Indians by eliminating one of their staples; in 1875, over a million buffalo were slaughtered.)

When Blake arrives at his destination — a nightmarishly squalid settlement of festering meanness and pollution — he’s told derisively by both Dickinson (Robert Mitchum), the blustering, hostile metal-works owner, and one of his henchmen (John Hurt) that they no longer need an accountant, having filled the position some time ago. After repairing to a saloon to spend the remainder of his meager supply of cash on a small bottle of whiskey, Blake runs into a former prostitute named Thel (Mili Avital) selling paper flowers and winds up in bed with her. Later that night Thel’s former lover (Gabriel Byrne) — who happens to be Dickinson’s son — bursts in and, after a brief exchange, shoots her dead and seriously wounds Blake in the chest with the same bullet. Grabbing Thel’s bedside pistol, Blake fires back three times, eventually hitting his assailant in the neck, and makes a clumsy getaway on the man’s pinto after falling out the window.

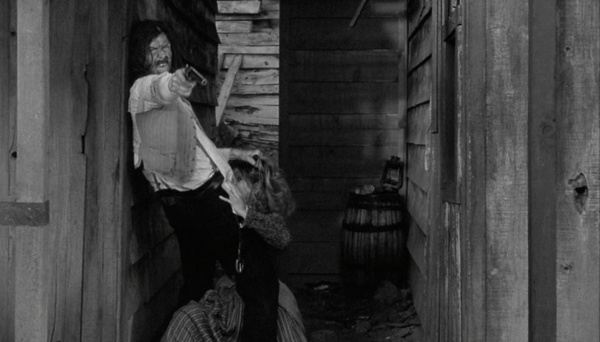

The first of many violent episodes in the film, this one sets the tone for Jarmusch’s distinctive, unnerving handling of violence. (“Why do you have this?” Blake asks Thel, fingering her gun before her former lover turns up. “‘Cause this is America,” she explains.) Every time someone fires a gun in this movie, both the gesture and its result are awkward, unheroic, even downright pitiful; it’s a messy act devoid of any pretense of stylishness or existential purity, creating a sense of discomfort and embarrassment in the viewer usually expressed in laughter. In this respect, it’s the reverse of the expressionist forms of violence taken for granted in commercial moviemaking ever since Bonnie and Clyde and The Wild Bunch, and recently granted a second life by De Palma, Woo, and Tarantino, among others: Jarmusch refuses to respect or valorize bloodshed. The film is no less honest about the allure of murderers in our culture; as Blake is gradually transformed into a cold-blooded killer, he takes on some of the “legendary” aura of a media star.

The next day in the woods we see Nobody (Gary Farmer) — a Native American outcast who’s half Blood and half Blackfoot — trying without success to remove the bullet close to Blake’s heart with a knife. Despite some mutual problems in understanding each other, they become riding companions. (Nobody, who was once taken as a prisoner to England and is well versed in the poetry of William Blake, is convinced that this Blake is the poet himself; Blake, who’s never heard of the poet, thinks that Nobody is crazy.) Nobody guides Blake through the wilderness toward the northwest coast, in effect leading him toward his own death. As Nobody points out, because the bullet in Blake’s chest can’t be removed, he’s already a dead man, and the remainder of the film is devoted to Blake’s adjustment to this fact. (It may be the most protracted death scene in movies; by comparison, Garbo’s death in Camille is a quickie.) In the meantime Dickinson has dispatched three bounty hunters to bring Blake back dead or alive, and he later offers rewards to various marshals and other bounty hunters. Putting a price on Blake’s head ensures plenty of skirmishes on their trek to the northwest.

There are several ways to categorize Jim Jarmusch’s six features to date. There are three in color (Permanent Vacation, Mystery Train, and Night on Earth), and three in black and white (Stranger Than Paradise, Down by Law, and Dead Man); clearly the second group is superior. Some have solitary heroes (Permanent Vacation and Dead Man), and some have clusters of heroes (the other four); the choice between these groups is much harder, because the first includes both Jarmusch’s thinnest and richest work — an apprentice piece and a masterpiece, both about solitude — and the second gives us another sort of movie altogether, minimalist entertainments in a theme-and-variations form.

With the enormous success of his second feature in 1984 — Stranger Than Paradise, playing at midnight this Friday and Saturday at the Music Box — Jarmusch became a figurehead for American independent cinema. He’s steadily rejected all Hollywood offers since (echoed in the response of LA taxi driver Winona Ryder to show-biz agent Gena Rowlands in the first episode of Night on Earth) and has cultivated a hip, international art-house reputation by acting in the films of such friends as Alex Cox, Robert Frank, Raul Ruiz, and the Kaurismaki brothers — creating a model for independence that combines the conviviality of the French New Wave with some of the down-home brashness of storefront theater.

Some viewers profess to have found a similar mix in Quentin Tarantino, but as far as genuine independence is concerned, there’s no contest. Jarmusch owns the negatives of all his features — something no Sundance favorite, including Tarantino, can claim. And not even Miramax, the most powerful American art-house distributor, has succeeded in wresting the final cut of Dead Man away from its writer-director — and don’t think it hasn’t tried. By contrast, Tarantino invites Miramax into his cutting room and happily relinquishes final control over his work for the sake of the distributor’s full support. He’s even been rewarded for his cooperation with his own distribution subsidiary at Miramax, Rolling Thunder, whose first two releases were Chungking Express and last week’s reissue of Switchblade Sisters.

With the help of unabashed Sundance and Miramax supporters like the New York Times‘s Janet Maslin — journalists eager to promote film as a business over film as an art, and therefore ready to place the future of cinema in the hands of producers rather than artists — the popular model for so-called American independence has now passed from Jarmusch’s freedom to Tarantino’s servitude. Take a look at the mostly negative American reviews of Dead Man and you’ll see Maslin is far from alone in this bias. Mainstream reviewers nowadays judge even big-budget commercial fare by the same rule-book prescriptions: though Jim Carrey is presumably powerful enough now to make some artistic choices of his own, he’s expected to adhere to the guidelines established in Ace Ventura and The Mask and not take any disturbing risks, as he does in The Cable Guy. (Though in this case the public already seems well ahead of the New York Times and Variety.)

Are we so dependent on movies that come to us exactly where we are — that flatter our current prejudices and enthusiasms and stroke our well-trained reflexes — that we can no longer sit still for movies that require even a modicum of adjustment? In New York, where Dead Man opened six weeks ago, the lack of comprehension — apart from a perceptive rave by the Village Voice‘s J. Hoberman and a couple of other reviews — has been close to total. Among the national reviews I’ve seen, David Ansen’s in Newsweek is a welcome relief from the rest. The New Yorker, which has been cluing us in to the high art of Boys and Mission: Impossible in extended reviews, didn’t even bother to review this picture in a capsule; and for all the film’s remarkable literary distinction, one can safely assume the New York Review of Books would sooner waste its pages on the latest Jane Austen film adaptation.

Thanks in part to the influence of New York minimalism, Jarmusch’s career has shown an exemplary balance between experimentation and repetition, between business savvy and artistic self-preservation. Moreover, he’s spiced the spare decorum of New York minimalism with the unruly, diverse charm of “foreign” and ethnic points of view, showing us New York, Cleveland, and rural Florida through the eyes of a Hungarian (Ezster Balint in Stranger Than Paradise), New Orleans and the wilds of Louisiana through the eyes of an Italian (Roberto Benigni in Down by Law), and Memphis and its rock shrines through the eyes of a Japanese couple (Mystery Train). Investing most of his energy in character rather than story, he returns repeatedly to looking at the same thing in different ways — or at different things the same way.

Permanent Vacation, Stranger Than Paradise, and Down by Law are all “road movies” of a sort, featuring music by John Lurie and strategic pauses in the dialogue. Yet each is a different form of road movie, with a different sort of Lurie music and even a different kind of silence, formally articulated in a different manner. Stranger Than Paradise and Down by Law follow two Americans and an unassimilated European wandering through a changing black-and-white landscape that remains obstinately the same. Yet few performances can be more dissimilar than those of Balint and Benigni; and the three locations in Stranger Than Paradise, shot by Tom DiCillo, are worlds apart from those in Louisiana — New Orleans, prison, swamp, and forest, shot by Robby Müller — in Down by Law.

The three-part construction of these two features carries over into Mystery Train, though here the time frame (one 24-hour stretch) and locations (a few dilapidated blocks in Memphis) remain the same in all three sections while the central characters are different. And in Night on Earth, in which Jarmusch moves from a three-part sketch film to a five-part sketch film devoted to five taxi drivers across the globe and their passengers, he retains the simultaneity of Mystery Train while altering its meaning by assigning four of the five sketches to different time zones.

Despite their formal ingenuity and diverse charms, Mystery Train and Night on Earth both indicated that Jarmusch was digging something of a rut for himself as a minimalist entertainer and hip, downtown-Manhattan mannerist. Though these films weren’t by any means devoid of thematic interest — for starters, both are preoccupied with death, anticipating Dead Man — they carried out their limited game plans a little too neatly. One felt Jarmusch was capable of more but hadn’t yet found the nerve to risk losing his constituency by pursuing it. Now that he’s found the nerve, it’s easier to see why he hesitated before making Dead Man — a project he’s been mulling over for years. Though he’s decisively turned a corner with this film and created his most accomplished and important work to date (as a friend remarked, extending the film’s references to the visionary poet Blake, this is plainly Jarmusch’s Songs of Experience), it’s clear he can no longer count on the critical support in this country that was there for him as a laid-back entertainer.

Very few Americans have seen Permanent Vacation, and judging from most of the domestic responses to Dead Man, not many will see it either — though it’s done reasonably well, or better, in most countries before arriving here. But thanks to Jarmusch’s international reputation and multicultural brand of filmmaking, he’s considered more a citizen of the world than an ordinary American director. Indeed, Dead Man begins with a quote from Henri Michaux (“It is preferable not to travel with a dead man”) that echoes the outsider views on America offered by Balint in Stranger Than Paradise, by Benigni in Down by Law, and by the Japanese couple in Mystery Train. Farmer’s robust, charismatic Nobody is the main character playing the “foreign” role in Dead Man — a fact touching on the scandal that Native Americans are treated in this country as if they were foreigners. Dead Man is one of the few westerns to see through the cheesy mythology that white people were the first North American settlers, but its approach is casual and poetic rather than preachy; the warm, comic friendship between Nobody and Blake, neither of whom entirely understands the other, is central to the film.

In many other respects as well Dead Man represents a fresh start, even a quantum leap for Jarmusch, in style as well as subject. (I’ve seen the film six times now, and each time it’s grown in beauty, resonance, and visionary power; as Hoberman puts it, “This is the Western Andrei Tarkovsky always wanted to make.”) The view of America offered here — not merely by Nobody but by the film itself — is a good deal darker and considerably scarier than anything in Jarmusch’s five previous features. Even though the film is set in the late 19th century (Jarmusch’s first foray into period filmmaking), the commentary on America in the 1990s couldn’t be more pointed — and grim, enough to make some viewers uneasy. Jarmusch’s meticulously researched and multifaceted approach to Native American cultures — which he respects without ever patronizing, idealizing, or otherwise simplifying — is in sobering contrast to his frightening portrait of white America as a primitive, anarchic world of spiteful bounty hunters, deranged trappers, and generally ornery individuals who regard every stranger as a moneymaking opportunity and/or object to be picked clean. Almost everything we learn about Nobody’s life derives from Jarmusch’s astute research into Native American cultures; what we see of white America derives from his research, poetic insight, and gallows humor.

The noblest antecedents of this disquieting apocalyptic portrait are literary rather than cinematic. Consider William Blake’s poem “London”:

I wander thro’ each charter’d street,

Near where the charter’d Thames

does flow,

And mark in every face I meet

Marks of weakness, marks of woe.

In every cry of every Man,

In every Infant’s cry of fear,

In every voice, in every ban,

The mind-forg’d manacles I hear.

How the Chimney-sweeper’s cry

Every black’ning Church appalls;

And the hapless Soldier’s sigh

Runs in blood down Palace walls.

But most thro’ midnight streets I

hear

How the youthful Harlot’s curse

Blasts the new born Infant’s tear,

And blights with plagues the

Marriage hearse.

And consider this from William S. Burroughs’s Naked Lunch: “America is not a young land: it is old and dirty and evil before the settlers, before the Indians. The evil is there waiting.”

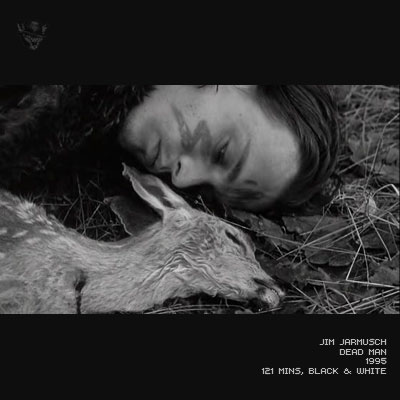

These passages, written a little over a century and a half apart, describe worlds in which evil and blight are metaphysical principles — the contemporary world for Blake, and a seemingly timeless one for Burroughs. In a way, Dead Man grows out of a horrified view of industrialized America compatible with the apocalyptic visions of both Blake and Burroughs, superimposed over an image of the American west haunted by the massive slaughter of Native Americans. And because it confounds much of our mythology about the western — reversing some of its philosophical presuppositions by associating a westward journey with death rather than rebirth, for example, and with pessimism rather than hope — a fair number of Americans aren’t ready for it. It implicitly rejects the current staples of commercial filmmaking — the feel-good slaughterfests of Woo and Tarantino, the affectless formalism and callow merchandising of MTV, the plot-driven buddy movie — choosing instead to meditate on the relation of death to the natural world. One key occurrence in the movie is the eerie, poetic, mystical moment when Blake, lost and alone in the wilderness, curls up alongside an accidentally slain fawn.

Notes on a few formal aspects of Dead Man:

The improvised minimalist score is by Neil Young. Most of it consists of electric guitar (with feedback) playing the same haunting theme, with variations, over and over; the remainder is performed on acoustic guitar, pump organ, and detuned piano and often registers as percussive sound effects, jolts of raw sensation. At times it calls to mind Jimi Hendrix’s “Star-Spangled Banner,” but its most often repeated phrase resembles, in both shape and feeling, “Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child,” pointing to the absolute aloneness of both Blake and Nobody, together and separately, even as friends and companions.

Robby Müller’s stunningly beautiful and exquisitely composed black-and-white cinematography, which includes a wide range of intermediate grays, is punctuated by fade-outs and blackouts between scenes, as if giving us forecasts of Blake’s death even before he’s wounded.

Jarmusch has said that the film’s odd, generally slow rhythm — hypnotic if you’re captivated by it, as I am, and probably unendurable if you’re not — was influenced by classical Japanese period movies by Kenji Mizoguchi and Akira Kurosawa. He seems to be referring to the tendency of scenes to exist in isolation from one another as complete units, like beads on a string, rather than as complementary elements glued together to suggest an unbroken continuity: in this respect the blackouts between sequences function like the empty spaces between stanzas in an epic poem. And the jangling, throbbing pulses of Young’s music — the only unambiguously 20th-century element in a 19th-century story — sometimes recall the Japanese music and percussion used in some Mizoguchi and Kurosawa films.

Dead Man proposes a cluster of metaphors: life as a journey (Blake’s journey unwittingly becomes a spiritual quest), white man as dead man, and poetry as something that white America is but doesn’t know and can’t understand. Some of the Blake adages Nobody quotes — such as “The eagle never lost so much time as when he submitted to learn of the crow” and “Drive your cart and your plow over the bones of the dead,” both from Proverbs of Hell — sound like Native American sayings to Blake and to us, and conversely some of Nobody’s pronouncements sound like the poetry of Blake. Depp’s luminous Blake, the central white man, is a blank sheet of paper that others — Dickinson, Nobody, the bounty hunters, the trio of trappers, the marshals, a racist missionary at a trading post, and even the original William Blake — cover with their manic scribbles. Finally their preoccupations about him become both his identity and his fatal destiny: his renegade badge of honor, “Some are Born to Endless Night,” is taken from his namesake’s Auguries of Innocence.

A key phrase of Nobody’s to describe death — “passing through the mirror” — has a lot of bearing on the structure of the film, which begins with Blake on a train carrying him toward a white settlement and ends with him in a sea canoe carrying him away from a Kwakiutl settlement. Blake’s glimpses of various activities during his initial walk through Machine (a freshly built coffin being placed upright, a horse pissing, and a man in an alley getting a blow job) are eventually matched by equally disorienting sights when, close to death, he passes through the Kwakiutl settlement.

This mirrorlike doubling crops up in many ways–most systematically during Blake and Nobody’s trek through the wilderness, when we see practically every landscape twice, first with them, then with the bounty hunters or marshals following behind. This looking at the same thing in different ways–the principle behind most of Jarmusch’s previous work — has a rhythmic and lyrical effect like the effect of repeated images and rhymes in a poem. Jarmusch has never been strong on plot–he fails to explain the logistics of the prison escape in Down by Law or the way the bounty hunters pick up Blake’s trail in Dead Man. He’s always closer to the form of a ballad, musically and poetically, than he is to the short story or novel.

A strange, poetic monologue on the train by the man who stokes the engine’s fire (Crispin Glover) simultaneously prefigures the film’s closing sequence (and conjures up water to “go with” the man’s fire) and resembles the sort of stoned rap one can imagine someone delivering in an earlier Jarmusch film: “Look out the window….Doesn’t this remind you of when you’re in the boat and then later that night you’re lying, looking up at the ceiling, and the water in your head was not dissimilar from the landscape, and you think to yourself, ‘Why is it that the landscape is moving, but the boat is still?'”

What such a monologue implies — the inability to distinguish between inner consciousness and external reality — is carried over in the remainder of the film with hallucinatory, and at times hallucinogenic, brilliance. Speaking to the bounty hunters in his office, Dickinson addresses his remarks to a stuffed bear; Cole Wilson (Lance Henriksen) — the craziest of the bounty hunters — reportedly “fucked his parents,” “killed them,” “cooked them up,” and “ate them.” Another bounty hunter (Michael Wincott) sleeps with a teddy bear and muses at one point, “Ever wish you were the moon?” When Wilson happens upon the corpses of two marshals (named Lee and Marvin), he notes that the head of one of them “looks like a goddamn religious icon” and promptly crushes it like a cantaloupe under his heel — an image of astonishing, shocking beauty. One of the lunatic trappers (Iggy Pop), who reads aloud to the others from the Good Book, wears a dress. Collectively they conjure up a crazed version of autodestructive white America at its most solipsistic, hankering after its own lost origins.

In more ways than one Dead Man can be seen as the fulfillment of a cherished counterculture dream, the acid western. This ideal has haunted such films as Jim McBride’s Glen and Randa, Dennis Hopper’s The Last Movie, Monte Hellman’s The Shooting and Two-Lane Blacktop, Robert Downey’s Greaser’s Palace, and Alex Cox’s Walker, not to mention such novels as Rudolph Wurlitzer’s Nog and Flats. Yet in some ways Dead Man goes beyond all of them in formulating a chilling, savage frontier poetry to justify its hallucinated agenda — a view at once clear-eyed and visionary, exalted and laconic, moral and unsentimental, witty and beautiful, frightening and placid. Turning the usual priorities of the western inside out to show us where we are today, Dead Man is as exciting and as important as any new American movie I’ve seen in the 90s. But it sure ain’t fashionable in these here parts, so you’d better check it out quick before it vanishes from the big screen.