From the Chicago Reader (July 19, 1996). — J.R.

Special Effects

Rating * Has redeeming facet

Directed by Ben Burtt

Written by Susanne Simpson, Burtt, and Tom Friedman

Narrated by John Lithgow.

Multiplicity

Rating * Has redeeming facet

Directed by Harold Ramis

Written by Ramis, Chris Miller, Mary Hale, Lowell Ganz, and Babaloo Mandel

With Michael Keaton, Andie MacDowell, and Harris Yulin.

The Frighteners

Rating — Worthless

Directed by Peter Jackson

Written by Fran Walsh and Jackson

With Michael J. Fox, Trini Alvarado, Peter Dobson, John Astin, Jeffrey Combs, Dee Wallace Stone, and R. Lee Ermey.

The Nutty Professor

Rating ** Worth seeing

Directed by Tom Shadyac

Written by David Sheffield, Barry W. Blaustein, Shadyac, and Steve Oedekerk

With Eddie Murphy, Jada Pinkett, James Coburn, Larry Miller, Dave Chappelle, and John Ales.

Looking around at the big summer movies, I see reason to assume that the state of the art of film art now equals the state of the art of special effects. The belief in capitalist growth as spiritual progress that permeates this culture seems to have been given particular currency: as film technology becomes more and more sophisticated, the art of film can only rise accordingly.

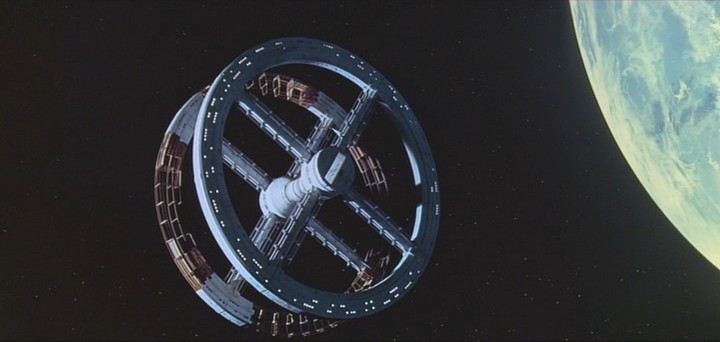

But does the development of morphing automatically make the Eddie Murphy Nutty Professor more artistic than the Jerry Lewis Nutty Professor (1963)? Is using four Michael Keatons in Multiplicity more artistic than using two Jeremy Ironses in Dead Ringers (1988)? Similarly, do we honor the special effects of George Lucas’s Star Wars trilogy or Robert Zemeckis’s Who Framed Roger Rabbit the way we honor such masterpieces as Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane and Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey?

I’d wager that the main reason we don’t is that the numerous trick shots in 2001 and Citizen Kane are subsumed under particular styles, forms, and visions; the only thing that might be called “special” about them in relation to other shots in each film is how they were achieved. Critic Annette Michelson noted back in the 60s that the seamlessness and continuity of 2001 dissolved the whole notion of the special effect, and the same thing could be said about Citizen Kane. By and large, the film business today is so bent on tweaking and revising whatever it has that it makes seamlessness neither likely nor desirable. And that makes the special effect — the disconnected detail and the privileged moment — easier for viewers to single out and praise. That special effects be regarded as the acme of movie art entirely suits the interests of commerce; it ensures that audiences will watch movies in a casual way, guaranteeing that a trip to the concessions counter won’t seriously interfere with what’s being offered.

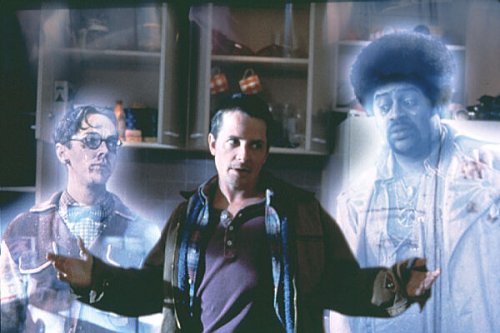

I guess if you’re disposed to get involved in the convoluted horror-comedy plot of Peter Jackson’s The Frighteners (Zemeckis served as executive producer) you might discover some sort of continuity beneath the barrage of special effects. But the ugly, aggressive, proliferating effects were all I could begin to contend with, and trying to keep interested in them was like trying to remain interested in a loudmouth shouting in my ear.

Admittedly, this is also what you have to put up with in the first section of Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket, but there the loudmouth — a marine training officer played by R. Lee Ermey — is part of a much larger design; in the second, longer section the dramatic effect is purposefully (if unsettlingly) dispersed rather than concentrated. I bring this up because Ermey turns up in The Frighteners, playing a ghost of essentially the same character, and the impact is reductive rather than artistic — you might say he’s become just another special effect.

Conceived and produced entirely in New Zealand, The Frighteners isn’t technically speaking a Hollywood movie, but if one regards Hollywood as a state of mind and bank account it’s hard to know what else to call it. The special effects were supervised by Wes Takahashi, who also worked on the effects animation in Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom, Who Framed Roger Rabbit, and the Back to the Future trilogy, as well as the computer graphic animation in The Mask.

Part of the distinction between special effects that allow a filmmaker to realize a particular artistic intention — such as the astonishing use of morphing as a narrative transition in The Neon Bible, when the hero grows from age 10 to 15 in a matter of seconds — and those that take the place of artistic intentions is obviously a matter of taste rather than something that can be determined scientifically. If you mosey on down to the Museum of Science and Industry to see Special Effects — a 40-minute Omnimax movie that aims for and achieves the experience of a theme-park ride — you’ll also be taking in some propaganda for the less artistic notion of the function of special effects. This production received major funding from the National Science Foundation, which is supported by our tax dollars, but postproduction facilities were provided by George Lucas. Most of the movie is an infomercial for the upcoming release of the “upgraded” Star Wars trilogy; it also shows how some jazzy effects in Kazaam, Independence Day, and Jumanji were achieved, providing additional commercial tie-ins. There isn’t much material here about morphing, but there’s a great deal about the use of scale models. Needless to say, Star Wars is singled out as “a turning point in special-effects history,” though 2001 isn’t even mentioned in passing. After all, Kubrick didn’t provide postproduction services — and why should our tax dollars support art when they can enhance something more permanent, like Lucas’s bank account?

It’s easy to see why Star Wars should be regarded as scientific, because science in our culture is often tied to the military-industrial complex, and because a Reagan weapons program was named after the film. As an exhilarating celebration of guiltless warfare, the whole trilogy might even be regarded as a sort of pilot for the gulf war, another spectacle of seemingly bloodless annihilation perceived as a video game — you could even leave the TV set for minutes at a time and not feel like you were missing anything.

The impressive thing about Multiplicity is that it gives us two, three, and eventually four Michael Keatons in the same shot. All are playing different versions of the same overworked construction-company manager, who’s decided to clone himself in order to do everything he doesn’t have time for. Less impressive is that none of these characters — each of whom has a distinct personality — is very compelling, nor are the manager’s wife (Andie MacDowell) or the guy who clones him (Harris Yulin), who has a clone of his own.

The concept is cute, the special effects (handled mainly by Richard Edlund) are smooth, and the story certainly has possibilities, but the characters are terminally dull. One of the Keatons, who’s supposed to be more domestic than the others, seems at first to have cliched gay mannerisms, but this is apparently just a reflection of Keaton’s limited repertory of telegraphable character types. After all, for this concept to work each character must be so simplistically conceived that you can recognize who he is in a flash. (In David Cronenberg’s premorphing Dead Ringers, where Jeremy Irons plays twins, the differences between the characters are less blatant, and Irons’s methods for signaling which character he’s playing are considerably more nuanced.) But the special effects are great.

Given my love and admiration for Jerry Lewis’s The Nutty Professor, I dreaded the prospect of an Eddie Murphy remake. According to Shawn Levy’s excellent biography King of Comedy: The Life and Art of Jerry Lewis, a sequel or remake has been in some sort of development purgatory for at least a dozen years, beginning as a sequel written by Lewis and Bill Richmond (who collaborated on the original) and turning into a Joe Piscopo vehicle with Lewis playing his father. After being shunted from Warners to Disney to Universal, the project mutated into an Eddie Murphy remake in 1994, with John Landis set to direct, though Tom Shadyac replaced him and rewrote the script with Larry Gelbart, who eventually bowed out as well. Lewis, by now effectively squeezed out of the project, “was assured an executive producer credit and a chance to appear in a small role,” according to Levy. He is credited as executive producer but doesn’t put in an appearance; whether this connotes disapproval on his part is anyone’s guess.

Without ever posing a serious challenge to the original, the new Nutty Professor is much more respectful of its source and funnier than I’d anticipated. The Dr. Jekyll-like title hero is now obese rather than a string bean and a klutz, and the Mr. Hyde-like Buddy Love is simply Eddie Murphy’s stand-up persona rather than the frightening, narcissistic greaser and nightclub crooner portrayed by Lewis. The comedy is considerably coarser and more sadistic, and the happy ending is devoid of the disquieting bitter irony that capped the original. Levy understandably expected that making the professor a fat man would remove “the pathos from the material,” but Murphy outdoes himself by bringing pathos as well as sweetness to the character, arguably making him a viable update of Lewis’s bucktoothed Julius Kelp. Considering that anxieties about weight and overeating are greater in our culture today than they were in 1963, one could even argue that the filmmakers have hit some version of comedy pay dirt, and the movie’s unabashed vulgarity on the subject might even be said to have something tonic about it.

So much for what I like about the remake, which is limited by three overlapping factors: (1) the absence of a single guiding artistic intelligence (unlike Lewis, Murphy functions as neither writer nor director, and too many cooks had a hand in this broth); (2) Murphy’s decision to hide behind makeup and padding in many of his characters and behind his own showbiz persona in the case of Buddy Love, refusing to place his real identity on the line; and (3) the frequent recourse to effects (supervised by Jon Farhat), which even at their most striking compound other problems.

Lewis’s Nutty Professor has a few surreal special effects of its own, but they’re used sparingly, and they never get in the way of Lewis’s performance or his personal vision of what the story’s about. (The most memorable comes in a gag in which Kelp drops a set of barbells and his arms stretch all the way to the floor.) In other words, they aren’t free-floating clutter — like those in The Frighteners and even some parts of the new Nutty Professor — but rather facets of the character and story, aspects of the filmmaker’s overriding vision.

On the subject of this vision Levy’s book is especially astute. The conventional critical wisdom about Lewis’s Buddy Love is that he’s a reincarnation of Dean Martin, but Levy points out that though it’s easy to arrive at such a conclusion, “it’s also facile and biographically unlikely.” After ticking off a dozen ways in which Love isn’t at all like Martin, Levy asks, “So if Buddy Love isn’t Dean, who is he? Well, Jerry Lewis, obviously. The cigarettes, the tyrannical outbursts, the overdone wardrobe, the fondness for brassy big-band swing, the hipster’s lingo, and the unctuous manner with the ladies were all attributes of Jerry’s private personality.” Levy goes on to argue no less persuasively that Kelp was just as clearly Lewis’s “own view of his deep-down inner self.”

Lewis’s Nutty Professor has both the comedy and the starkness of one man’s rigorous self-scrutiny, combining self-love and self-hatred with a moral virulence and rare courage that remain at the center of Lewis’s performance as both characters. (In contrast to the continuity and focus of this performance is the more typical discontinuity of his enjoyably self-referential but far from confessional appearance as the Devil in Damn Yankees, currently at the Schubert — a theatrical turn full of allusions to earlier stages in his career and usually positioned at an oblique angle to everything else in the production.) Morphing and heavy makeup would only interfere with that process and distract us from what it means. Lewis gives himself a pair of false buckteeth as Kelp and in his climactic transformation from Love to Kelp employs a straight cut to get us past the visual difference, but all his other transformations between the two characters are performed on camera, and they’re central to the movie’s affective power — its comedy as well as its pain.

Murphy’s transformations, by contrast, are sleights of technology and makeup in which nothing truly personal is ever at stake; the jazzy effects, enjoyable for their own sake, ultimately refer only to themselves. Murphy’s own nutty professor, Sherman Klump, can grow to the size of a skyscraper — a likely steal from Tex Avery’s animated King Size Canary — or morph to Buddy Love and back again with an extravagance of effect but a minimum of expressiveness or soul. Murphy plays all but one of the members of Klump’s family, in some of the brassiest and funniest moments of this movie’s burlesque, but not in a way that tells us anything of importance about himself. Lewis tells us just about everything, and the exposure cuts to the bone; Murphy gives us some tolerable light entertainment, with plenty of opportunities to duck out to the candy counter.