From the Chicago Reader (December 13, 1996). — J.R.

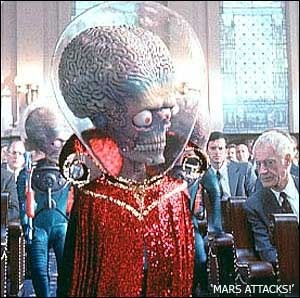

Mars Attacks! ***

Directed by Tim Burton

Written by Jonathan Gems

With Jack Nicholson, Glenn Close, Annette Bening, Pierce Brosnan, Danny DeVito, Martin Short, Michael J. Fox, Rod Steiger, Tom Jones, Lukas Haas, Natalie Portman, Jim Brown, Lisa Marie, and Sylvia Sidney.

By Jonathan Rosenbaum

As light entertainment, Mars Attacks! gave me more pleasure than most other recent movies I’ve seen, including Daylight, The English Patient, Independence Day, Jingle All the Way, 101 Dalmatians, Space Jam, Trees Lounge, and 2 Days in the Valley. Maybe this is because it achieves the level of nonseriousness so many of its competitors aim for, a level the mass media have been touting as the ideal for big-time movies. If that ideal is to keep you enthralled for a couple of hours and leave a minimum of aftertaste, then Tim Burton’s SF comedy pretty much fills the bill. It also made me laugh.

Part of what kept me so absorbed — apart from the neatly designed effects and a few of the actorly turns, including Jack Nicholson’s — is the sense the film conveys of postmodernist free fall through the iconography of 50s and 60s science fiction in relation to the present: a singular sense of giddy displacement that clearly locates the movie in the 90s, but a 90s largely made up of images and cliches from previous decades that are subtly turned against themselves, made into a form of camp, affectionately mocked, yet still revered as if they had a particular purchase on the truth. Or perhaps they never had a purchase on the truth but are simply dumb and beautiful, like the fleet of flying saucers that appears behind the opening credits.

Most reviewers have been describing the movie as satire, but whether it’s the cold war or the present that’s being satirized is far from clear — and if it’s both, it’s still unclear where this movie stands in relation to the two. A similar form of ambiguity could be found in Ed Wood, Tim Burton’s previous feature, which oddly wound up making a failed artist of the 50s into a 90s hero — a kind of postmodernist transubstantiation that could only be carried out by altering both Wood and the 50s. Another significant though less obvious cross-reference is the 1984 film adaptation of George Orwell’s 1984 — coscripted by the same English playwright, Jonathan Gems, who scripted Mars Attacks! — which was less postmodernist and more historical in the way it deftly incorporated 1948, the year Orwell’s novel was written, into its image of the future.

This movie’s most obvious and most acknowledged source is a series of trading cards briefly issued by the Topps Company in 1962; the fact that they’re rare and legendary today gives them some of the aura of Ed Wood’s features. The only other sources deemed worthy of mention in the press materials are “classic alien invasion films of the 50s and 60s” — an ambiguous cycle, since I can’t determine what the unclassic alien-invasion films of the 50s and 60s might be (are they all classics by definition?). Certainly the BEMs (bug-eyed monsters, in 50s SF lingo) in Mars Attacks! are creatures that can be traced back to 50s and 60s pulp-magazine covers and illustrations as much as to movies of the same period.

But two other influences are no doubt equally important — Stanley Kubrick’s 1964 Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb and a few Joe Dante movies, especially Gremlins (1984), Explorers (1985), and Gremlins 2: The New Batch (1990). From Strangelove comes an overall satirical impulse grounded in cartoonish characters, a basic crosscutting structure and rhythm that moves between the president of the United States and various other characters and locations, the actor playing the president reappearing in one or more other parts (Peter Sellers in Strangelove, Jack Nicholson in Mars), and a central “war room” where a jingoistic top general (George C. Scott in Strangelove, Rod Steiger in Mars) petitions the president to go nuclear in the middle of a global crisis. From the Gremlins movies comes the overall concept of aliens that cackle like bratty teenagers, mock and destroy humanity with gratuitous glee, and bleed a gooey green substance; from Explorers comes their propensity for hovering in orbit over earth while picking up TV signals and creating garbled hybrids of human life and culture inside their spaceships.

But it’s mainly the striking differences from Kubrick’s and Dante’s movies that make Mars Attacks! interesting as well as fun — differences that are both historical and ideological. Strangelove regards the potential annihilation of the world as grotesquely and horribly funny, but Mars Attacks! treats it as little more than a riff or a goof — a premise to hang gags on. Similarly, Dante’s nostalgic evocations of 40s, 50s, and 60s Americana are laced with more than a little pickle juice, but Burton’s use of similar emblems doesn’t have a comparable sense of period or ethical nuance. Most different is Burton’s sense of what should or shouldn’t be open to ridicule, which has direct consequences for his characters.

The main earthbound settings in Mars Attacks! are Washington, D.C., Las Vegas, and Kansas. Fully open to ridicule in the first city are the president of the United States, the first lady (Glenn Close), the bellicose General Decker (Steiger), the peace-loving and self-regarding General Casey (Paul Winfield in a role clearly meant to suggest Colin Powell), the whoring press secretary (Martin Short), and the president’s key scientific adviser (Pierce Brosnan), who’s both liberal and falsely urbane (he has an English accent, smokes a pipe, and assures everyone that the arriving martians mean no harm). Much less open to ridicule are the president and first lady’s daughter Taffy (Natalie Portman), who’s about the same age as Chelsea Clinton; a bus driver and single mother (Pam Grier); and the bus driver’s two sons, who play hooky in a video arcade (good practice, it turns out, for using the martians’ ray guns against them).

In Las Vegas the estranged father (Jim Brown) of the two boys, a former professional boxer, is the only character relatively untouched by the filmmakers’ scorn, despite the fact that his job as a casino greeter dressed like a pharaoh is designed to make him look ridiculous. Everyone else — a greedy real estate salesman (Nicholson glorying in prime slime) and his New Age wife, a former alcoholic (Annette Bening); a vulgar gambler (Danny DeVito); and Tom Jones (playing himself as a club headliner) — is simply ridiculous. The same goes for a fashion-crazy newscaster (Sarah Jessica Parker), her fastidious newscaster boyfriend (Michael J. Fox doing a rough approximation of CNN’s Wolf Blitzer), and a gun-toting hillbilly family living in a Kansas trailer park — with the exception of a kid brother named Richie (Lukas Haas) and his semisenile grandmother (Sylvia Sidney), both of whom are outcasts.

In short, apart from the four black characters — all of them admired for their resourcefulness and determination — the only other human figures who aren’t viewed as geeks and washouts (even when they’re viewed with some affection, as is Tom Jones) are a couple of preteen kids (who meet cute at the end of the picture) and an old woman who barely knows what’s going on: a half dozen outsiders who wind up as virtually the only survivors of the martian invasion. This isn’t to say that these characters are viewed without irony. Taffy is seen at one point reading Hermann Hesse’s Siddhartha, and in his final hero’s speech Richie suggests that maybe mankind would be better off living in tepees — two indications that they’re really just a couple of hippies. But implicitly at least they and the grandmother and the black family (and Tom Jones, out of courtesy) deserve to survive. Just about everyone else is wiped out — and not at all missed.

I’ll never forget the rude shock of my first experience of Dr. Strangelove when I was a college undergraduate. I went with my best friend and his girlfriend, and when we emerged she was in tears, horrified that the end of the world could be treated as a joke. Some of our response was undoubtedly the effect of Kubrick — all of whose films are scary and creepy on some level — but some of it was the effect of the cultural atmosphere surrounding the cold war. That atmosphere was quite different from today’s; it’s certainly different from the comic atmosphere of Joe Dante’s films, even when they’re concerned with apocalyptic situations (as in the Gremlins movies) or with war fever (as in Matinee), as well as that of Spielberg’s 1941, with its Tinkertoy quality.

The Gremlins movies have only a few human deaths, and 1941, if memory serves, has none at all. But Mars Attacks! features the death by ray-gun fire of practically every ridiculed character cited above and a good many others as well, including all of Congress — and it’s never creepy or scary or upsetting in the slightest. It’s just a goofy kick. We see one character after another reduced to a skeleton before the bones disintegrate, and we admire the special effect more than we mourn the person. This isn’t, I think, because Tim Burton is more malicious or heartless than Kubrick or Dante or Spielberg; on the contrary, Burton’s tone tends to be sweeter than theirs. But his representation of human beings is far more abstract and alienated — a perspective I suspect many people share. Maybe that’s why his movie can seem equally scornful of pacifists and warmongers, capitalists and ecologists, xenophobes and xenophiles; why it can reject politics in any form, can delight in the destruction of most of this country and its population — and not seem subversive or especially cynical about it.

Of course it’s also because this movie, like Ed Wood, is in love with silliness. It doesn’t exactly side with the inscrutable, malevolent, and asexual martians (all of whom, we’re told, lack genitalia), but it shares more than a few of their traits, such as a mischievous desire to scramble parts of kidnapped earthlings to see what emerges (a newscaster’s head grafted onto her dog’s body and vice versa) — a graphic illustration of the postmodernist impulse itself. But if I had to cite the eeriest special effect in Mars Attacks! it would be the Jayne Mansfield-like blond who lures the press secretary to his doom in the White House’s Kennedy Room and who turns out to be a martian in disguise. What’s eerie as well as comic about this effect — a parody of 50s female sexuality — is that the figure doesn’t look remotely human, though it’s played by Lisa Marie (who played Vampira in Ed Wood).

Turning life into nonlife, nature into artifice, history into style, and reality into cliche is in a way what all Hollywood movies do on some level. Maybe what I like about Mars Attacks! — even if it freaks me out to think about it — is that it’s so up front and cheerful about this process that it shows us something of who we are these days, who we were, and what we’ve lost.