From the Chicago Reader (November 14, 1997). –J.R.

Fast, Cheap & Out of Control

Rating **** Masterpiece

Directed by Errol Morris

With Dave Hoover, George Mendonca, Ray Mendez, and Rodney Brooks.

To name an object is to suppress three-fourths of the enjoyment of the poem, which is composed of the pleasure of guessing little by little: to suggest…that is the dream. –Stéphane Mallarmé

If narratives are arrangements of incidents with precise beginnings, middles, and ends, then Errol Morris’s exciting and singular Fast, Cheap & Out of Control doesn’t really qualify. You can’t even call it a documentary in any ordinary sense, because you often can’t say exactly what’s being documented. I suspect that poetry offers a better model for what Morris is up to, particularly Mallarmé’s idea of what poetry should be: an obscure object shaped and defined in successive increments by the reader’s perception and imagination.

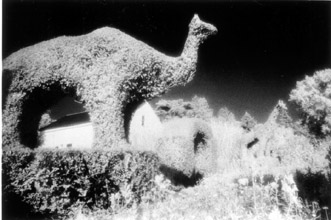

Four men are interviewed separately in Morris’s film — a lion tamer (Dave Hoover), a topiary gardener (George Mendonca), a mole-rat specialist (Ray Mendez), and a robot scientist (Rodney Brooks) — and they recount the origins as well as some of the development of their passion for their work. Who they are apart from their work almost never comes up. We do learn early on that Mendonca married his employer three years after he met her and that Hoover had a fleeting friendship with circus lion tamer and 30s film star Clyde Beatty, his role model, but these are the only instances in which other characters impinge on the professional concerns of these men. Even Morris as interviewer allows his own voice to be heard only once — when he asks Hoover toward the end, “Do you miss Clyde Beatty?”

Some of the footage that accompanies the talk is conventionally illustrative — showing us lion taming, topiary gardening, mole rats, and robots. Some of it is more associative — showing us circus performers, a cavorting bug in an animated cartoon, and old movie serials featuring Beatty, a robot, predatory winged creatures, and toppling buildings. What begins as a specific illustration of something one of the four men is saying sometimes mutates into something else entirely, and what begins as a nonspecific illustration of what one man is saying sometimes winds up illustrating much more precisely what another man says just afterward. Many of the passages of black-and-white “found” footage from the serials begin to seem like a kind of dream material relating to the past and to the imaginations of the four men, who are usually shown talking in color. But the contemporary black-and-white footage of circus performers, topiary gardens, mole rats, and robots makes it impossible to mark the points at which “fact” gives way to “fiction” and life gives way to reflection.

The commingling of all these diverse materials may add up to a narrative of some kind — perhaps even one with a beginning, a middle, and an end (which would support the comparison some critics have been making with D.W. Griffith’s 1916 epic Intolerance, another film that alternates between four stories). But defining this movie as a narrative forces us to ask, A narrative about what? If instead we decide to define it as a poem, we can ask a better question: what does it do, and how does it do it?

Rightly or wrongly, most of Morris’s previous nonfiction films — Gates of Heaven (1978), Vernon, Florida (1981), and A Brief History of Time (1992) — have gained him the reputation of being something of a geek collector, or at the very least a filmmaker who cultivates eccentrics. (The Thin Blue Line, from 1988, doesn’t quite fit this pattern, and I haven’t seen his 1991 fiction feature, The Dark Wind.) The overall thrust of these three films has a lot to do with either the strangeness of the people he’s filming or the strangeness he produces by filming them. Indeed, Morris’s edge as a filmmaker — what might be described as his gift and his magic if one likes what he’s doing, his evasiveness and his condescension toward his material if one doesn’t — stems in part from the fact that we can’t always be sure how much of this strangeness is a matter of content and how much is a matter of style.

The new film’s title derives from a statement by Brooks, the robot scientist, about the kind of small robots he’d like to see invading the solar system — “fast, cheap, and out of control.” Those words might also apply to Morris’s film, which moves briskly, was cheap to make, and is out of control insofar as it qualifies as an “open” text — a do-it-yourself (or glue-it-yourself) kit that obliges each viewer to synthesize his or her own meanings out of the crisscrossing discourses provided by the four interviewees and all the supplementary materials. Indeed, one of the fascinations of this film is the way in which taming lions, topiary gardening, studying mole rats, and designing robots function as metaphors for Morris’s own activity as a filmmaker.

To call Fast, Cheap & Out of Control an open text doesn’t mean that Morris isn’t in firm control of the form of his work; indeed, a successful open work, in contrast to a merely sloppy or random one, has enough formal rigor to limit a viewer’s choices, not simply to allow a chaotic free-for-all where any and every meaning is possible. In this film the relationships between the four men being interviewed — some of them highlighted by formal means such as juxtapositions or overlaps of sound or image — aren’t simply spoon-fed to us but are allowed to emerge from the material in different configurations, according to how we read the sounds and images in relation to one another.

Case in point: Before the interviewees are identified, even before the credits, the film shows us grainy, hallucinatory black-and-white glimpses of (1) tiny robots moving awkwardly across a landscape, (2) someone in a skeleton suit chasing a clown (in both rapid and slow motion) around the periphery of a circus arena, (3) two reptiles (or are they mole rats?) fighting on a rocky surface, (4) an old gardener walking through a topiary garden, (5) a close-up of a sunflower, and (6) a lion terrorizing African natives until a boy with a spear chases the animal away. The last segment — apparently drawn from a Clyde Beatty serial, either The Lost Jungle (1934) or Darkest Africa (1936) — continues after Beatty appears, with dialogue about a missionary who disappeared in the jungle several years before and a legendary lost city. Only after all of this do we get our first color shots, identifying the Clyde Beatty circus in the present, followed by the beginning of the credits, then another shot from a black-and-white Beatty serial, and finally color footage of Hoover, the wild-animal trainer, saying that as a kid he wanted to be Beatty.

I’ve arbitrarily put this prefatory black-and-white material into six categories. But most of these segments consist of more than one shot, and the separations between the segments aren’t always clear-cut; we might read the close-up of the sunflower, for example, as a detail in the topiary garden, which appears in the preceding shot, or as an establishing shot for Africa in the sequence with the lion that follows. And thanks to the dreamlike stylistic unity provided by the same grainy black-and-white textures in the first five of these segments (followed by the more conventional black and white of the clip from the Beatty serial), as well as the unity provided by Caleb Sampson’s highly effective score (which plays a major role in structuring the entire film), most of the actions seem to be taking place on roughly the same terrain: even if the vegetation glimpsed in the robot footage clearly doesn’t belong inside the circus tent, it could easily be imagined adjacent to where the reptiles or rats are fighting, which could also be read as Africa — a connection we might make semiconsciously before we encounter either the African lion or Ray Mendez, the mole-rat specialist, telling us that mole rats come from Africa. In other words, our ordinary viewing habits, which are dependent on narrative linkage between shots, impose various kinds of continuity on these opening segments, placing them in the same world — literally or figuratively in the same space, poetically within the same universe — before we even meet the four men who explicate these images.

About eight and a half minutes into the film, after we’ve been introduced briefly to all four of the interviewees, Brooks, the robot scientist, recounts some of his experiences with robots at MIT. As he talks, there’s a matching cut from a robot moving across a landscape to Beatty and the African boy moving across an African landscape, presumably toward the “lost city.” It’s a moment that poetically “confirms” the narrative continuity we’ve already intuitively imposed during the film’s prologue, and it lays the groundwork for a system of rhymes that increasingly take on thematic properties as the four men speak about their separate professional concerns.

It’s largely up to the viewer which of these thematic rhymes becomes most prominent, because the film gives us plenty to choose from, among them death, predatory combat, theatricality, coordination and its absence (such as the circus performers versus the robots), deductive reasoning and its absence (the lion tamer versus the lion, Mendez and Brooks versus their objects of study), the struggle to control nature (a concern of all four men).

Morris’s principal role as ringmaster in this poetic enterprise is to establish the way the four main discourses make a kind of music, separately as well as collectively. Each discourse is set mainly to a different rhythm and tempo: much of the Mendonca footage moves in stately and elegiac slow-motion; the Mendez footage usually moves in a frenetic scherzo. Brooks’s lumbering, stumbling robots define a kind of broken rhythm, while Hoover inside the lion cage often alternates between staccato flurries of movement and nervously guarded stasis. Setting these rhythms and tempi against one another, Morris invites viewers to join in with their own musical agendas, to trace their own perceptions over the choices offered. The beauty of this measured but collaborative activity is that it yields melody, not cacophony. No two viewers’ melodies are likely to be the same — which is why I’ve been avoiding the temptation to privilege mine here — but the shapeliness of the film ensures that all of the possible melodies can be sung together.