From the Chicago Reader (August 18, 2000). More recently, Naomi Klein, one of my heroes, has written about some of the more salient differences between the WTO demonstrations and the more recent ones on Wall Street: see, for instance, this article, as well as others on her website. — J.R.

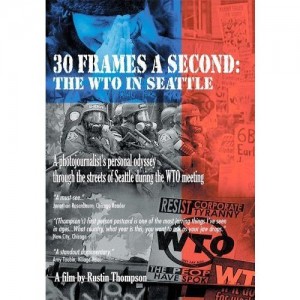

30 Frames a Second: The WTO in Seattle

Rating *** A must see

Directed and written by Rustin Thompson.

If I had to review Rustin Thompson’s video documentary 30 Frames a Second: The WTO in Seattle in only three words, I’d say it’s honest, energizing agitprop. Some readers may regard this as an oxymoron, but it’s one account of the Seattle events I’ve been waiting for, receiving its world premiere at the Chicago Underground Film Festival this Sunday at 1:30 PM. Yet the information it has to convey is almost entirely of the you-are-there variety — there’s no genuine analysis. It evokes 60s demonstrations in a number of ways — including such standbys as bare-breasted, body-painted teenyboppers and burning dollar bills — and pays particular attention to the music performed by demonstrators (one folksinger even sounds like Arlo Guthrie), coming much closer in feeling to something like Woodstock than to radical 60s documentaries produced by Newsreel. But it’s a good deal more personal than either genre. In fact, what marks 30 Frames a Second as agitprop is Thompson’s own political conversion, seemingly brought about by his participation in the events.

The phrase “preaching to the converted” is frequently trotted out to express disapproval of political statements. When it was recently used in a review of Ron Mann’s Grass, I wanted to reply, “OK, fair enough. But so are The Deer Hunter, Star Wars, Mississippi Burning, Saving Private Ryan, and most James Bond and Woody Allen films — not to mention Nike ads, Disney World, and every piece of idiotic antimarijuana legislation that’s ever been passed.” In the case of 30 Frames a Second, I’m again one of the converts, and Thompson — who wrote, directed, taped, edited, and coproduced this video with his wife, Ann Hedreen — is clearly another.

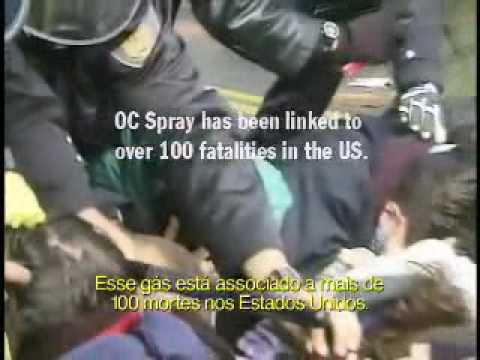

In fact Thompson, who’s worked for 19 years as a cameraman, producer, and editor on network news shows and local newscasts in Seattle, reports that he received press credentials to cover the World Trade Organization’s convention last December as an independent journalist; he didn’t even have a clear sense at the time of what the WTO was. (Pointing out in the voice-over that he’s “traveled to a few exotic countries” and “won some Emmy awards,” he adds that he’s been disillusioned about much of his work, feeling like “an overpaid electronic stenographer.”) Cruising the streets of downtown Seattle, he found his feelings ran increasingly against the police and for the demonstrators who wanted to shut down the WTO meeting (and eventually succeeded). He didn’t even make it over to the convention center until the fourth day, where it appears he stuck around only briefly, getting a few interviews. The real story here is what he found in the streets — what the demonstrations looked, sounded, and felt like, given the rain and tear gas — and a little bit of what these events got him thinking about.

Thompson’s apparent naivete ensures that a significant part of his thinking is his discovery that Americans aren’t as politically apathetic as he’d assumed (“My illusion of a meek, complacent population was forever shattered”) and that some are even incensed about the abuses and ravages of multinational corporations. Indeed, for him this documentary is first and last an American story — and I have to confess that when I first read about the protests in Seattle, I leaped to a similarly shortsighted conclusion. Like Thompson, I felt that the resurgence of 60s activism I’d expected at some point was finally taking shape, though the fresh alliances making it possible were reconfiguring old party lines and political divisions; but I also regarded the event somewhat more broadly as a happy sequel to Tiananmen Square in spring 1989. Still, it was hard not to read the demonstrations in ethnocentric terms.

For some cynics it’s virtually impossible for agitprop to be honest, which suggests that to be energized by it necessarily means to be duped. But it’s hard to know what being duped by 30 Frames a Second would mean, because Thompson admits at the outset, “I don’t know if I can tell all sides of the story — or just the story the way I saw it.” He’s not even sure what image might be the best one to start with, though finally he settles on an instance of police violence on the second day, which he later returns to and puzzles over, trying to figure out why this particular cop lost it while others didn’t. Almost apologetically, not wanting to seem pretentious, he shows Michel Subor delivering a famous quote in Jean-Luc Godard’s second feature, Le petit soldat (1960): “Photography is the truth. And film is the truth 24 times a second.” Thompson goes on to insist that “even at 30 frames a second, the speed of videotape, truth is still subjective. It can only be what I choose to contain within the four walls of my viewfinder.”

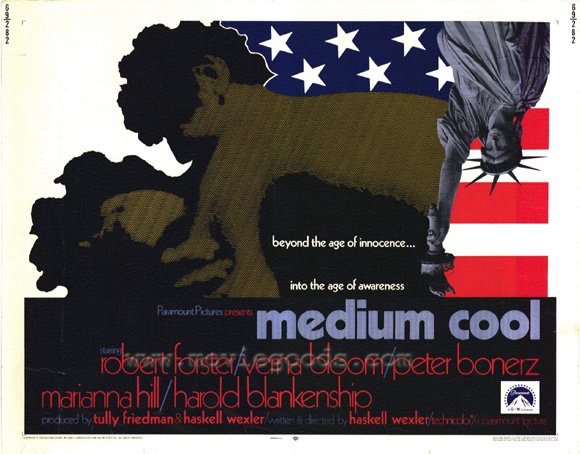

Obviously what interested Thompson most is also what I most wanted to see — material about the demonstrations that didn’t make it onto the news. But both of us needed some historical context for the events in Seattle, and both of us found somewhat mythic substitutes. Thompson includes two other short film clips in 30 Frames a Second, one from Haskell Wexler’s Medium Cool, a film about the 1968 Democratic convention riots that’s a touchstone for 60s activism, and the other from the last scene in John Ford’s The Grapes of Wrath, a 1940 touchstone for 30s populism. I guess leapfrogging from California in the 30s to Chicago in the 60s to Seattle in 1999 represents some kind of history, however telescoped, but it’s a history of feeling, not of thought or achievement. Even Thompson’s subtitle, The WTO in Seattle, seems a bit off-kilter, pointing not to his real subject but to the event that occasioned the demonstrations.

I’ve seen 30 Frames a Second twice. In between these viewings I spent the better part of a day devouring Naomi Klein’s exciting, fact-filled, intelligent No Logo: Taking Aim at the Brand Bullies, which deserves to be regarded as the bible of the global movement that converged in Seattle: certainly it crystallized my own sense of mythos and agitprop, analyzing the phenomenon of “branding” and the protests it’s provoked. Klein’s book came out last year, so she makes no mention of what happened in Seattle (she should write an afterword for the paperback), but she explains in copious detail what led up to that international uprising. In fact her book is an ideal complement to Thompson’s video, because each zeroes in on what the other excludes — though Klein’s wealth of material, offered over 490 pages, goes far beyond Thompson’s 73 minutes about a single event. What they have in common is an individual partisan response that acknowledges their own experiences and biases — allowing us to look over their shoulders while they arrive at their conclusions, something I don’t find in Nike ads for all their aspirations toward global culture and universality.

Perhaps Klein has something of an edge on Thompson because she lives in a relatively marginalized country, Canada, rather than a monolith like China, Russia, or the United States, where practically everything tends to get translated into nationalistic terms. Klein’s parents are Americans who emigrated to Canada in the 60s in protest against the war in Vietnam, so you might say she has an especially good vantage point from which to judge the relationships between her subject, the United States, and the 60s. (She’s also pretty good at critiquing her own, more narrow political interests in the 80s: “In [our] new globalized context,” she observes fairly early, “the victories of identity politics have amounted to a rearranging of the furniture while the house burned down.”)

For Thompson, being reminded of the 60s is what seems to get his motor running, but I can’t figure out exactly where he wants to go with this energy. The fact that the people he videotapes are mainly American — except at the convention center, where he seems to favor foreigners — inevitably locates him on the periphery of the multinational world Klein is writing about, but if he’s aware of this limitation he doesn’t mention it. “This is not an American agenda, this is a human agenda,” someone at a rally is heard saying toward the end of the video. But you wouldn’t know that from Thompson’s approach.

He reminds me of myself in the 60s when I started to resee my hometown in Alabama, reimaging it through the eyes of people from all over the country I’d met on the last leg of the march from Selma to Montgomery — a crowd so richly diverse yet so bound together by common values and feelings that it was exhilarating to be part of it. I was being altered by the experience, but seeing it only in relation to my hometown was just a tentative first step toward understanding what was happening and what transformative possibilities lay ahead.

Klein views branding and activist responses to it as being in symbiotic relationship, an interaction highlighted in a couple of key passages in different parts of the book. “Branding…has taken a fairly straightforward relationship between buyer and seller and — through the quest to turn brands into media providers, arts producers, town squares and social philosophers — transformed it into something much more invasive and profound. For the past decade, multinationals like Nike, Microsoft and Starbucks have sought to become the chief communicators of all that is good and cherished in our culture: art, sports, community, connection, equality. But the more successful this project is, the more vulnerable these companies become: if brands are indeed intimately entangled with our culture and our identities, when they do wrong, their crimes are not dismissed as merely the misdemeanors of another corporation trying to make a buck. Instead, many of the people who inhabit their branded worlds feel complicit in their wrongs, both guilty and connected. But this connection is a volatile one: it is not the old-style loyalty between lifelong employee and corporate boss; rather, this is a connection more akin to the relationship of fan and celebrity: emotionally intense but shallow enough to turn on a dime.”

“Despite the rhetoric of One Worldism, the planet remains sharply divided between producers and consumers, and the enormous profits raked in by the superbrands are premised upon these worlds remaining as separate from each other as possible. It is a tidy formula: because the [subcontracted] factory owners in the free-trade zones don’t sell a single Reebok sneaker or Mickey Mouse sweatshirt directly to the public, they have a limitless threshold for bad public relations. Building up a positive relationship with the shopping public, meanwhile, is left entirely in the hands of the brand-name multinationals…. Despite the info-tech hype, only corporations [believe themselves] capable of genuine global mobility. It is this supreme arrogance that has made brands like Nike and Disney so vulnerable to the two principal tactics employed by the anticorporate campaigners: exposing the riches of the branded world to the tucked-away sites of production and bringing back the squalor of production to the doorstep of the blinkered consumer.”

Klein also notes that branding attempts to eliminate the negative connotations of “Coca-Colonization” by globalizing its own products. “The buzzword in global marketing isn’t selling America to the world, but bringing a kind of market masala to everyone in the world. In the late 90s, the pitch is less Marlboro Man, more Ricky Martin: a bilingual mix of North and South, some Latin, some R&B, all couched in global party lyrics. This ethnic-food-court approach creates a One-World placelessness, a global mall.”

The activists’ movement is no less global in its aspirations, reaching “well beyond labor unions” and incorporating members “young and old; they come from elementary schools and college campuses suffering from branding fatigue and from church groups with large investment portfolios worried that corporations are behaving ‘sinfully.’ They are parents worried about their children’s slavish devotion to ‘logo tribes,’ and they are also the political intelligentsia and social marketers who are more concerned with the quality of community life than with increased sales.” Bound together by common goals rather than by nationality or location, activists are literally all over the place.

Perhaps the key problem for “no logo” partisans — especially acute for citizens of the larger countries who can’t get enough foreign news — is simply finding out what’s going on. This is why Klein’s book and Thompson’s video both have the force of revelation. For me, some of the most fascinating bits in No Logo concern the playful, exuberant radicalism of an international movement called Reclaim the Streets. According to Klein, this group staged 30 events in 20 countries on May 16, 1998 — though these were “rarely reported as more than isolated traffic snares” — involving “Indian farmers, landless Brazilian peasants, unemployed French, Italian, and German workers and international human-rights groups.” The events ranged from 800 people dancing on a six-lane highway in Utrecht to even larger bashes in Prague, Sydney, Berkeley, Birmingham, and Geneva. If you’re wondering what this self-styled “Global Street Party” had to do with multinational brands, it was planned to coincide with the G8 summit in Birmingham, England — two days before the same economic leaders from the same prosperous countries proceeded to the 50th anniversary celebration of the WTO in Geneva, where activists’ partying and rioting lasted for several days. In other words, the eruptions in Seattle last December were only continuations of actions challenging the WTO a year and a half earlier.

It’s obvious that seeing this global protest movement in terms of an American resurgence in activism is only sampling a small piece of the pie. And despite Thompson’s clips, nationalities and political loyalties are no longer defined the way they were in the 30s or 60s, especially now that governments kowtow to the brands rather than the other way around. (A Washington-based labor activist explains in Klein’s book that he focuses his efforts on the Nike corporation “because we have more influence on a brand name than we do on our own governments.”) Thompson’s interest in a march of 50,000 people organized by Teamsters and another march of steelworkers against the WTO seems motivated by the irony of these “mainstream” American political groups joining forces with young activists.

I don’t think this focus, with its attendant omissions, necessarily indicates any shortsightedness in Americans. And as Klein shows in detail, the fact that our lives are affected by the same brands around the planet guarantees that we have much more common cause than we did during the 60s, for example, when European and American activists were more prone to inspire one another than to collaborate. Thanks to the Internet, there’s a growing constituency of world citizens becoming more interactive daily. But most of the brands that cater to this savvy crowd seem invested in the premise that they’re simply hicks or unthinking Americanophiles incapable of processing or responding to any more challenging information than a TV ad. There’s a similar hell of self-fulfilling prophecy in Klein’s chilling tale about a Georgia high school principal who was so serious about a competition sponsored by Coca-Cola in 1998 that she suspended a senior for turning up on official Coke Day wearing a Pepsi T-shirt. For me the creepiest aspect of this story isn’t the principal’s intolerance, as it was for Klein, but the senior’s limited options for meaningful rebellion, harking back to the sterility of either-or thinking during the cold war.

The legacy of that period continues to hold us back. Insofar as branding typically aspires to the same sort of planned culture that we used to associate with Stalinism, it could be argued that the triumph of capitalism on the economic front has been accompanied by the triumph of Stalinism on the cultural front — even if it’s Stalinism with a capitalist face, or what Klein calls “a colonization not of physical space but of mental space.” 30 Frames a Second and No Logo both represent healthy steps toward decolonizing our consciousness, though they proceed on separate fronts and speak to different needs — emotional in the first case, intellectual in the second.