From the Chicago Reader (May 11, 2000). — J.R.

The Gleaners and I

Rating *** A must see

Directed and narrated by Agnes Varda.

Documentaries are a discipline that teaches modesty. — Agnes Varda, quoted in the press notes for The Gleaners and I

There’s a suggestive discrepancy between the French and English titles of this wonderful essay film completed by Agnes Varda last year. It’s a distinction that tells us something about the French sense of community and the Anglo-American sense of individuality — concepts that are virtually built into the two languages. Les glaneurs et la glaneuse can be roughly translated as “the gleaners and the female gleaner,” with the plural noun masculine only in the sense that all French nouns are either masculine or feminine. The Gleaners and I sets up an implicit opposition between “people who glean” and the filmmaker, whereas Les glaneurs et la glaneuse links them, asserting that she’s one of them.

Gleaners gather up the leftovers of edible crops — grain, fruit, vegetables — after the harvesters are finished with their work. Varda la glaneuse films what other filmmakers have left behind after their harvesting. The link between the two activities is made graphic at one point when Varda gleans a potato with one hand while filming it with the other. She keeps shifting between the kinds of gleaners she finds — in paintings as well as life — and her own diverse gleaning activities, such as bringing back souvenirs from Japan or collecting memorabilia on her road trips while making this film. She also does such things as film the veins in her hand to record the process of her aging.

“Filming” is only an approximation of what Varda does, because her equipment consists of a DV Cam and a Mini DV, both of which use digital videotape that’s later transferred to 35-millimeter film. There’s been a lot of discussion lately about what digital video does for and to filmmaking, and The Gleaners and I demonstrates the positive consequences better than any other documentary I know. (The fiction feature that best does this is also French, Jean-Pierre Sinapi’s wonderful 1999 Nationale 7, which has been shown here just as part of the members-only series Talk Cinema; sad to say, there are no plans to distribute it locally.)

One obvious thing that digital video does is place people on both sides of the camera on something that more nearly resembles an equal footing. A 35-millimeter camera creates something like apartheid between filmmakers and their typical subjects, fictional or nonfictional — because between them stand an entire industry, an ideology, and a great deal of money and equipment. This is the subject of many of Abbas Kiarostami’s major features, including Homework, Close-up, Life and Nothing More, Through the Olive Trees, and The Wind Will Carry Us; he recently shifted to DV in part because he wanted to achieve something closer to equality with whom and what he shoots. Similarly, Varda wants to be one gleaner among others — part of a spectrum of individuals, ranging from homeless scavengers to artists, who roam the street looking for “found” objects to work with.

Some of the owners of orchards and fields interviewed by Varda tolerate or even welcome gleaners, but others won’t permit them on their property. None of them seems quite as heartless as the restaurant proprietors I used to hear about when I lived in Santa Barbara in the mid-80s, who put poison in their garbage cans to ward off the homeless — a policy that might well be resurrected in the age of George W. Bush, whose first priority is clearly the comfort of the rich. People who already have everything often believe they deserve to keep even what they can’t use from people who have nothing, though that philosophy certainly isn’t restricted to the rich. There’s a priceless moment in Bela Tarr’s Satantango when the bestial members of a failed farm collective completely dismantle a crummy set of bureau drawers before they leave so that Gypsies can’t use them.

Gleaning can be subversive because it redistributes goods and also because it sometimes undermines conventional class distinctions and definitions of privilege. For instance, every week for many years, my youngest brother, a social worker in London, would load up a van with food whose expiration dates had passed from the posh Marks and Spencer and deliver it to shelters for battered women and similar institutions. He would be given some of the food as a reward, and it’s significant that some of the city and country gleaners interviewed by Varda go scavenging for leftovers not because they have to but because it enhances their lives, philosophically or practically. One chef says he learned the practice from his grandfather, and he continues it because it teaches him what he can get and where; a frequenter of city fruit and vegetable markets who’s gainfully employed explains that he simply hates to see food go to waste.

It’s a sad fact that so-called essay films — even exceptional ones such as Chris Marker’s Sans soleil, The Last Bolshevik, and One Day in the Life of Andre Arsenevich — almost never succeed commercially. But The Gleaners and I — which may be the most Marker-like of Varda’s essay films, thriving on digressions and even featuring a cat, the ultimate Marker totem, in its opening shot — has been proving unusually popular with audiences and critics. Last fall it won both the People’s Choice Award at the Montreal International Festival of New Cinema and New Media and the Gold Hugo for best documentary at the Chicago International Film Festival. Late last month two dozen international critics at the Buenos Aires International Independent Film Festival, which I attended as a jury member, gave it more than twice as many votes as any of the hundreds of other contenders in the voting for favorite films. The festival proved that independent films, when not up against the advertising budgets of Hollywood pictures, can draw substantial crowds; the seven-hour Satantango, for instance, sold out both times it was shown, and large crowds also turned up for all kinds of experimental and essay films, including several by Marker. The festival, financed by the city of Buenos Aires, did so well that the local commercial cinemas suffered as a result.

I think that part of what critics and audiences respond to in Varda’s work is her utter lack of pretension and her capacity to tackle several interlocking subjects, personal as well as general, without any sense of strain. She can leap from a Burgundy vineyard owner who forbids gleaning to another wine grower who doubles as a psychotherapist and is interviewed with his wife, then move abruptly to another couple in a cafe who talk about how they met, then return to the subject of gleaning, then cut to herself picking and tasting a fig in a fourth location and commenting on its heavy alcoholic content. However, this pleasurable sense of drift may also be what ultimately makes this film fall just short of being a masterpiece — because it refuses to develop or build on its insights.

“I like filming rot, waste, leftovers, mold, trash,” Varda declares with pride at one point in the film. Born in Brussels in 1928, she’s justifiably known as the grandmother of the French New Wave, having started out as a filmmaker in 1954, shortly after Marker and Alain Resnais, both of whom are somewhat older. Yet she’s never achieved the preeminence of some of her “grandchildren” — actually her contemporaries — such as Jean-Luc Godard or Francois Truffaut. I don’t think this can be explained solely by the fact that she’s a woman. She’s made 16 short films and 18 features to date, but many of them are almost impossible to get, which is why I’ve seen less than half of them. I suspect one reason distributors haven’t picked up many of them is that they think her abiding interest in the marginal and ephemeral, along with a certain unevenness, won’t draw viewers.

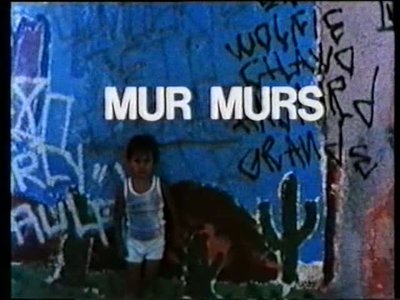

Of her previous documentaries I’ve seen, the one that most resembles The Gleaners and I is the 1980 Mur murs — another playful title that literally means “wall walls” — which is about mural art in Los Angeles, the making of which seems almost as furtive as gleaning. There’s something fairly off the map about many of her fictional characters as well, including the title protagonists of what may well be her two best features, Cleo From 5 to 7 (1961) and Vagabond (1985). These characters are defined by dawdle and drift as much as Varda is in The Gleaners and I, catching life on the fly — and implicitly inviting us to do the same.