A column for Caiman Cuadernos de Cine, submitted in May 2021. — J.R

One of my major recent activities, probably shared by most of my readers during the pandemic, is finding “new” (that is to say, unfamiliar) films to watch online. So, after reading a 1970 interview with the usually publicity-shy Elaine May in the New York Times, where she cited “Holiday for Henrietta” (La fête à Henriette, 1952), a film I’d never heard of, and Anchors Aweigh (1945), an MGM musical I only dimly recalled from childhood, as particular favorites, along with The Wizard of Oz (1939), I treated the first two of these idle references as recommendations, meanwhile wondering if they might also provide certain clues to or predictions of May’s own filmmaking practices in A New Leaf (1971), The Heartbreak Kid (1972), Mikey and Nicky (1985), and/or Ishtar (1987).

Well, Anchors Away at least offers some predictions. It costars Gene Kelly and Frank Sinatra as sailors on leave in San Diego and Hollywood—Kelly a brash extrovert and womanizer, Sinatra a shy introvert, anticipating the respective male duos of Nicky (John Cassavetes) and Mikey (Peter Falk) in May’s third feature, and even the blatant casting-against-type of Chuck (Dustin Hoffman) and Lyle (Warren Beatty) in her fourth. There are gags reversing gender stereotypes (such as a row of MGM ingenues wolf-whistling at Kelly when he walks past them) and issues of lying and betrayal, the theme uniting all four of May’s features, with married heterosexual couples instead of buddies infected with lies and betrayals in the first two.

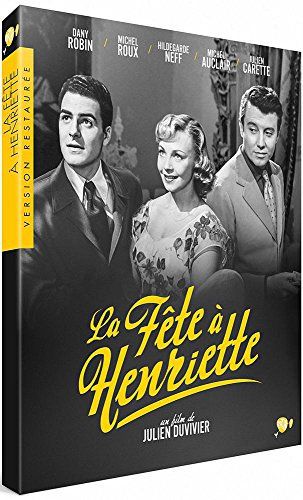

The major revelation was La fête à Henriette, directed and cowritten by Julien Duvivier, a lively deconstructive farce that plays with a few romantic rivals and betrayals of its own. After a slew of literally blank opening credits asserting that this film hasn’t yet been made or even written, we’re introduced to a pair of quarrelsome screenwriters in a country retreat whose latest effort was just squelched by censors, and who now try to conjure up a new script — a love story set in Paris on Bastille Day — after combing a newspaper for ideas and finding there only the premises of a couple of recent Italian neorealist hits. They keep disagreeing about the characters and plot of their own story, and the Duvivier film proceeds to illustrate their alternate suggestions in turn as they provide them in voiceovers and cutaways. Modestly cast (the only actors I immediately recognize are Hildegarde Knef and Julien Carette), this has a Maylike capacity to situate avant-garde impulses inside a mainstream context. Along with her gallows humor and particular talent for creating lovable monsters, this is one of the many outsider traits that she shares with Stroheim.