From the Chicago Reader, March 28, 2003. I was shocked learn on January 30, 2010 about the freakish and accidental death of Karen Schmeer, the gifted editor of The Same River Twice as well as many of Errol Morris’s films (including my favorite, Fast, Cheap, & Out of Control), in New York City, when she was hit by a car speeding away from a drugstore robbery — J.R.

The Same River Twice **** (Masterpiece)

Directed by Robb Moss.

Stevie **** (Masterpiece)

Directed by Steve James.

The first Chicago International Doc Film Festival is drawing to a close this weekend. Critics tend to make assumptions about the State of Cinema as if that were a knowable entity, generalizing on the basis of the few crumbs of pie the film industry and the media toss us. But we’re forced to face the inadequacy of those assumptions when something like this documentary festival demonstrates that the pie is a lot larger than we thought.

Two powerful documentaries screening this week — The Same River Twice, showing as part of the festival on Sunday at Facets Cinematheque, and Stevie, starting a regular run at Landmark’s Century Centre — make an instructive pair. Both are serious efforts to sum up major portions of their subjects’ lives, moving back and forth between past and present to reflect on what time has or hasn’t done to these people. Both contain a great deal of searching analysis. And though both only rarely address the issue of class directly, we may conclude that class has a lot to do with their subjects’ fates.

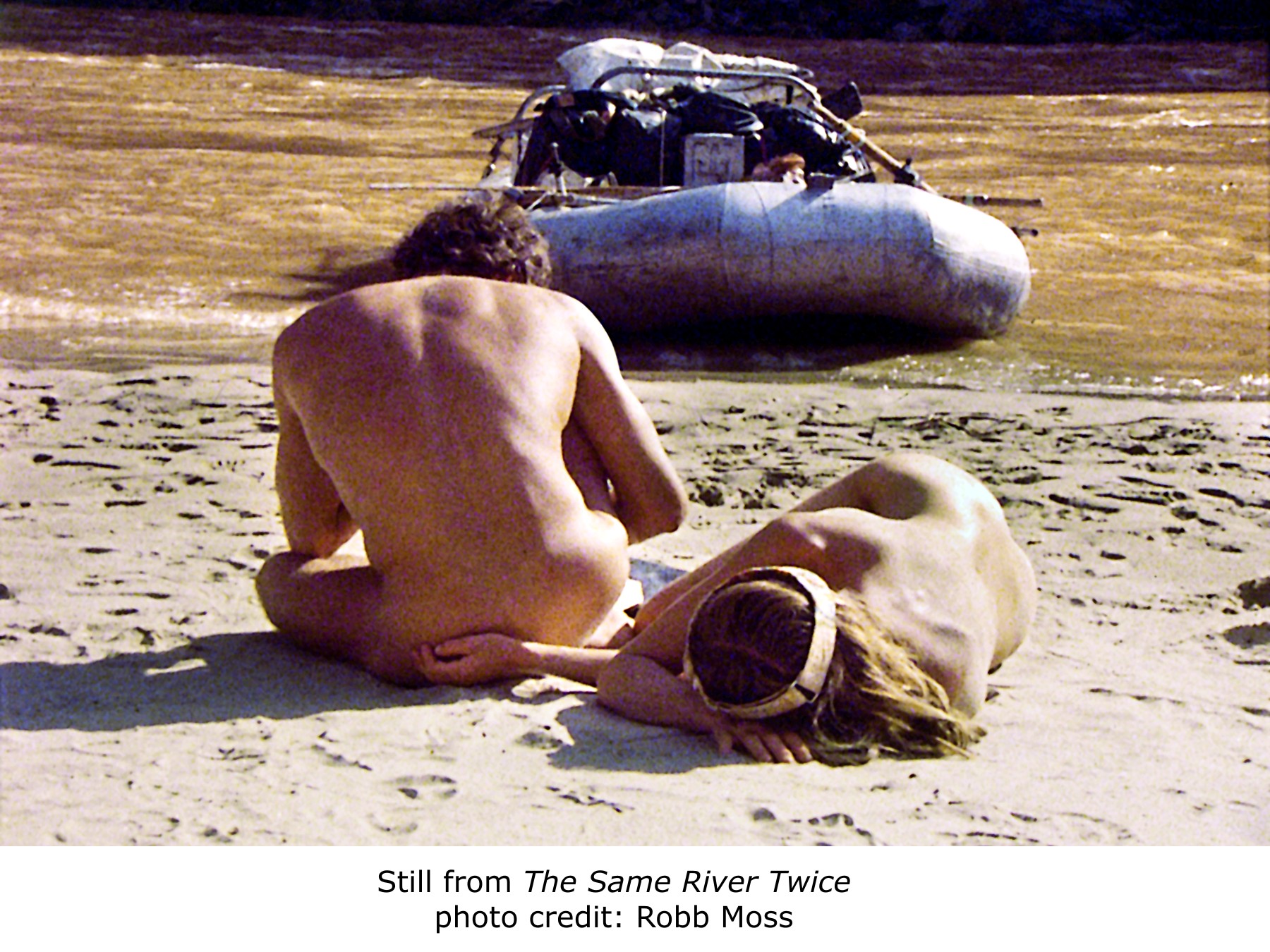

There’s something quintessentially American about this preference for addressing class issues indirectly, through issues that have class implications: family, job choices, religion, moral values, social philosophies. Stevie presents a bleak view of human destiny, focusing on the life of Stevie Fielding, who was a rejected, deprived, and abused illegitimate child in rural southern Illinois in the mid-80s, when filmmaker Steve James, the middle-class director of Hoop Dreams, served as his Big Brother. James was in the area ten years later and reestablished contact with Stevie, who was eventually incarcerated for sexually abusing a little girl. The Same River Twice presents a relatively positive and hopeful picture of a group of hippies who took a river trip together in 1978 near the Grand Canyon, which one of them, Robb Moss, filmed. Moss picks up their story again 20-odd years later, exploring who they were then, who they are now, and how their lives still intersect.

Neither film indulges in facile attempts to use social determinism to explain its subjects. Instead they both show us people who’ve made significant and determining choices about their lives. Yet looking at the two films together, one could easily conclude that Stevie Fielding has led a doomed life because of his unstable and violent upbringing, while most of the people in The Same River Twice have led charmed lives because of their relatively stable and secure childhoods — which is the unstated subtext of much of the counterculture. The possibility that Stevie’s life might have developed differently if he’d been able to stay with the two loving and nurturing foster parents he had early on is emphasized late in the film, when he goes to visit them after many years of not seeing them — a heartbreaking sequence that spells out precisely what his life has been missing.

One could even argue, somewhat bluntly, that The Same River Twice is largely about growing old gracefully and Stevie is largely about not growing old gracefully — and that one reason for the difference is the simple luck of the draw. It’s worth noting that Stevie is getting a commercial run in Chicago, while the no less worthy and enlightening The Same River Twice is showing here only once — the luck of another kind of draw. (The Same River Twice was just completed, so perhaps it will still land a distributor — yet another issue of luck, for us as well as the filmmaker.) It could also be argued that Stevie has commercial credentials The Same River Twice lacks: a single story line that allows a tighter narrative focus, an affecting score (by Dirk Powell) that helps to draw us emotionally into certain moments, and an occasional use of close-ups that makes Stevie function more like a feature film than a documentary.

Theoretically, the frequent nudity of the hippies in 1978 and the mainly upbeat treatment of these five people in the present could be seen as commercial qualities, but the film doesn’t treat them as if they were. Yet intermittently The Same River Twice does function like a commercial narrative film, albeit in less obvious ways than Stevie. We’re almost always aware that we’re watching a documentary, but Moss does such a good job of keeping himself out of the story, apart from his role as unseen interlocutor, that in one scene I suspect he tricks us the way a commercial director would. Two of the former hippies, Jeff and Cathy, were a couple in 1978, later married, separated at some point before 1998, and now live across the street from each other. At one point in the film Jeff, looking at some of the 1978 footage, gets a call from Cathy and tells her jokingly that he’s just been watching her butt. We cut from him to Cathy hanging up the phone in her kitchen as if it were the end of the same call, but since Moss is the only credited cinematographer and couldn’t have been in two places at once, this implied sequence is impossible. Other examples of narrative continuity make us realize that Moss is as much a storyteller as a chronicler: part of what makes The Same River Twice great is its highly selective and shaped methods of portraying the individuals, almost as if they were fictional creations. The way in which the present gradually overtakes the past in this film is more evidence of Moss’s flawless sense of narrative construction.

Another reason I value The Same River Twice is its generational bias. The euphoria and values associated with the counterculture of the 60s and 70s, in particular its pantheism, are so often treated with skepticism or cynicism that it’s refreshing to see them represented sympathetically — and in a fashion that evokes some of that period’s zeitgeist. These five individuals clearly loved nature and have managed in their separate ways to sustain this love into their middle years: all of them live outside cities, and idealism still appears to be part of their everyday lives. Jeff has been promoting an ecological novel he’s written, and Cathy, who’s been mayor of a small town for nine years, says she would be happiest if she could support herself by waiting tables or driving a bus; she seems to get the most pleasure picking vegetables in her own garden.

This doesn’t mean the film avoids troubling subjects, such as what drove Jeff and Cathy apart, Barry’s testicular cancer and his failure to be reelected mayor of another small town, as well as the inability of his mother to either die or enjoy life. Jim — seen as a “river deity” and model for some of the others in 1978 — has worked almost continuously as a river guide since 1973 and at first appears to be the happiest of the five, yet he eventually comes across as a rather sad figure because of his isolation. He has made only slow progress on building a house for himself, and a friend of his makes some illuminating remarks late in the film about his difficulty in sustaining a romantic relationship.

Part of what’s so compelling about this film is the graceful and telling way it cuts back and forth between these characters in 1978 and today, catching their evaluations and reevaluations of their earlier selves and letting us see continuities and discontinuities across two decades. The title obviously derives from Heraclitus — “You can’t step into the same river twice” — though at times Moss seems to intend it be taken ironically, since some of the characters seem to be trying to step back in again, at least in their imaginations. A woman named Danny says the nakedness of her and of her friends in 1978 still looks perfectly natural, and Moss asks, “Why did we do it?” She laughs and says, “Because we could.” And there’s a heart-stopping moment when Cathy, reacting to footage showing her and Jeff together, says, “I was so in love with him. I worshiped him….It took a lot to undo that” — a moment that makes the subsequent Hollywoodish fade-out the scene’s only possible conclusion.

It seems reasonably safe to assume that most of the people who go to see The Same River Twice or Stevie will be middle-class. I point this out because these films ask to be read from middle-class perspectives, those of the two filmmakers. We hear more than see Moss, but he clearly establishes himself as the implicit narrator with just a couple of early intertitles. Stevie makes the first-person status of the narrator-filmmaker central from the outset, and this puts us more in the position of sympathetic observers than of potential participants. If we identify with anyone in this story, it’s likely to be Steve James.

Stevie is seen mainly as a closed book the film and filmmaker — and with them the audience — try to open. This could be regarded as the effort of guilty liberals: just as James clearly feels some responsibility for Stevie, we’re asked to ponder what went wrong in Stevie’s life to make him sexually abuse a child and then be in denial about it — an attitude that helps determine his fate. Are “we” — that is, the social system that we, actively or passively, help keep in place — in any way responsible, or are we blameless? The film doesn’t say, and it’s to James’s credit that he gives us many opportunities to think about this question without pushing us toward any conclusion. And he gives us plenty to consider when he shows us the response to Stevie’s crime and his character by practically everyone in his immediate circle, including his mother, his step-grandmother (the person who did the most to raise him, 50 yards from his mother’s house), his sister, his fiancee, and the mother of the girl he molested.

We’re implicitly asked, for instance, to ponder the fact that his fiancee, with whom he lives, considers him guilty of sexual abuse but also loves him and refuses to reject him because of it. Does this make her wrong? Right? Neither? Over the course of the film we become aware that Stevie’s mother is in denial about some of her abuse of Stevie as a child. But we also become aware of her remorse, especially after her religious conversion, and learn that she may be trying to make amends by visiting her son in jail. Such scenes force us, like James, to consider ethical choices we don’t customarily face. In one remarkable sequence a former prison inmate, a member of the Aryan Nation, announces that he can help protect Stevie during his stint in prison — but only if James, not Stevie, asks for this help. We’re implicitly asked to put ourselves in James’s shoes, and we may come away feeling that throughout his life Stevie has had to make questionable alliances and choices normally unthinkable from a middle-class perspective.

One might conclude that the enormous value of a film like Stevie lies in its ability to take us places we’d probably never go otherwise — not merely as guilty liberals, but as thinking individuals who want to learn something about the world we inhabit. The considerable value of The Same River Twice lies in its getting us to ponder things we probably already know something about. That’s a much more comfortable experience, yet both films are strong enough to teach important things about our lives and the lives of others. We don’t get a lot of opportunities for this when we go to the movies, so we should cherish the few that come along.