From the March 19, 2004 issue of the Chicago Reader. — J.R.

Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed by Michel Gondry

Written by Charlie Kaufman, Gondry, and Pierre Bismuth

With Jim Carrey, Kate Winslet, Elijah Wood, Mark Ruffalo, Kirsten Dunst, and Tom Wilkinson.

How happy is the blameless vestal’s lot!

The world forgetting, by the world forgot.

Eternal sunshine of the spotless mind!

Each pray’r accepted, and each wish resign’d;

Labour and rest, that equal periods keep;

“Obedient slumbers that can wake and weep;”

Desires compos’d, affections ever ev’n,

Tears that delight, and sighs that waft to Heav’n.

–Alexander Pope, “Eloisa to Abelard” (1717)

Only once in a blue moon does a screenwriter who isn’t a director become known as an auteur. Plenty of distinctive movie writers have reputations as actors or as actor-directors, starting with such giants as D.W. Griffith, Charlie Chaplin, and Erich von Stroheim, but they’re rarely celebrated for their writing. You have to go back to Robert Towne, who’s done only a little directing, and Paddy Chayefsky, who never did anything but write and produce, to find auteurs known mainly as writers.

A Chayefsky movie isn’t hard to identify, but I think it’s safe to say that these days a Charlie Kaufman movie is even more recognizable. On the basis of just four original scripts — Being John Malkovich, Human Nature, Adaptation, and now Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind — he’s achieved a public identity few other screenwriters in history have acquired.

All of these movies are founded on goofy, surrealist fantasies concerning the thwarted desires of neurotic and ineffectual characters, and all have scrambled methods of telling a story, including juggled chronologies and viewpoints. It’s refreshing that Kaufman is using his growing fame to make his experimentation even more audacious and complex, trusting his coworkers and audiences to be equally adventurous.

It’s important to acknowledge that Kaufman has become an auteur in the public consciousness, but it’s equally important to understand that auteurism is more a way of viewing films than a formula for understanding how films are created. The screenplay of Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind is credited to Kaufman, an American screenwriter, but the story was initially hatched by two Frenchmen –Michel Gondry and Pierre Bismuth. Gondry, who’s known mainly for his music videos (including those for Bjork), directed only one previous feature, Human Nature, for which Kaufman wrote the script, and perhaps it’s telling that the two other features with original Kaufman scripts were directed by Spike Jonze, also known mainly for his music videos. (Confessions of a Dangerous Mind, which Kaufman adapted from Chuck Barris’s autobiography, was the first directorial effort of actor George Clooney.)

In Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind he clearly surpasses himself. For the first time he delivers an ending that doesn’t feel like either a cop-out or a throwaway, even if it’s Hollywood to the core. He’s also figured out a structure that perfectly matches the emotional tenor of his theme and isn’t just an amusement-park ride that can be forgotten as soon as it’s over. Furthermore, he’s working with people — notably writer-director Gondry, cowriter Bismuth (a visual artist), and actors Jim Carrey, Kate Winslet, Elijah Wood, Mark Ruffalo, Kirsten Dunst, and Tom Wilkinson — who are willing to serve the screenplay as a team rather than take it as an opportunity to show off. One result is that Winslet is more demonstrative than Carrey, in keeping with the characters they’re playing. Another is that Gondry as director pushes himself beyond Human Nature, astutely underscoring the fluidity of certain mental transitions by using stage techniques such as quick lighting and scenery changes and film techniques such as shifts in focus and digital alteration.

It could be argued that in spite of all their giddy and hilarious screwball elements, Kaufman’s features are largely about the desire of tormented neurotics to obliterate themselves. Eternal Sunshine — whose central couple, apart from their suicidal tendencies, bear more than a passing resemblance to Woody Allen and Diane Keaton in Annie Hall — addresses this theme more directly than the other Kaufman films, using a setup suggested by Bismuth and elaborated by Gondry: a company called Lacuna helps lovesick people recover by obliterating their memories of their former partners. Significantly, the question “Is there any danger of brain damage?” gets the immediate reply “Technically speaking, the procedure is brain damage.” The movie introduces this as a science fiction concept, yet it feels too contemporary to belong in the future. Indeed, it might be said to already exist in a less targeted form when people elect to undergo shock therapy.

We learn about the company and its business somewhat belatedly, after the hero, Joel (Carrey), describes meeting the heroine, Clementine (Winslet), a ditsy Barnes & Noble clerk, on the Long Island Rail Road. There’s an unexplained blip in the narrative after they return from their first date, a drive to the Charles River in Massachusetts, and as the credits come on, the film abruptly shifts to Joel in anguish after their relationship has ended. The blip is a repressed memory, and it’s eventually accounted for because the film is constructed like a Mobius strip.

Joel gets a card from the company telling him that Clementine has decided to have him erased from her memory and he’s not to contact her. He visits the Lacuna office and meets the staff — a receptionist named Mary (Dunst), a doctor named Howard (Wilkinson), and two assistants, Stan (Ruffalo) and Patrick (Wood) –and finally decides to erase his memory of Clementine. (His surname is Barish, which suggests both “banish” and “perish.”) He’s told to bring to the office all the objects he owns that remind him of Clementine, after which Stan and Patrick will come to his apartment while he’s asleep and complete the erasure.

This is where the movie really takes off, because no matter how convoluted and contrived the setup becomes, the articulation of it is so precise and finely calibrated that we accept it. We discover that Patrick met Clementine when her memory was erased and is now dating her — and telling her things Joel once told her, which he learned during her erasure process. Mary, who lives with Stan but secretly loves someone else, comes over to Joel’s apartment during his erasure to keep Stan company, after which Patrick leaves to go see Clementine. Mary and Stan then get stoned and wind up dancing in their underwear over Joel’s sleeping body. Because no one’s paying close attention, Joel’s erasure, part of which we see from his viewpoint, goes haywire: pieces of the past and present run together, resulting in a surreal narrative free fall.

All of this probably sounds hyperbolic and self-indulgent — and there are plenty more outlandish spins to come. But the script and its delivery are so disciplined and masterful that the twists are surprisingly easy to follow. (I saw this film twice, once with the press and then at a public preview; the audience seemed more sympathetic and attentive the second time.) At first Stan and Mary dancing in their underwear over Joel’s inert body on his fold-out sofa seems like a cruel screenwriter’s conceit. But in this movie, execution is almost everything, and the poetic aptness of one lovesick individual being indifferent to the lovesickness of someone else makes the concept work.

The movie has one particularly interesting if obscure source that can probably be attributed to one of the Frenchmen who worked on the script: the fifth feature of Alain Resnais, Je t’aime, je t’aime (1968), an SF curiosity scripted by surrealist Jacques Sternberg that may be the most underrated and neglected of Resnais’ features (though one can order a blotchy video dupe with subtitles from Video Search of Miami).

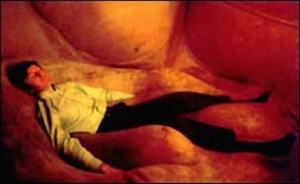

The plot follows the free fall of a man who attempted suicide and has been enlisted in a time-travel experiment that goes awry, setting him helplessly adrift in his own memories, most of which concern a failed relationship with a woman who’s since died. Resnais’ film also expresses the same tone of irreconcilable lament as Kaufman’s. I would have seen these similarities as a coincidence if it weren’t for a virtual quote of one of Resnais’ signature shots — the man stretched out on the all-enveloping, billowing waterbedlike floor of the time machine, which resembles a giant brain.

I’d nominate Resnais as the most lyrical narrative auteur alive, as well as the unacknowledged inspiration for most of the significant narrative experiments in movies since the 60s. (I’m not counting gimmicky and unpoetic counterfeits like Memento or Irreversible, but I am including, just for starters, 8½, The Exterminating Angel, The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie, Celine and Julie Go Boating, The Shining, Naked Lunch, Groundhog Day, The Lovers of the Arctic Circle, In the Mood for Love, and 25th Hour.) As a director-auteur who selects his screenwriters and shapes his scripts without writing, Resnais is the opposite of Kaufman, but I think I can claim that none of Kaufman’s scripts would have been possible without his example. Now 82, Resnais recently released in France his sublime Pas sur la bouche (“Not on the Mouth”), an eccentric and beautiful adaptation of a 1925 comic operetta that’s showing in New York later this month but may not reach Chicago for quite some time (though you can find trailers and bits of the score on the Internet).

For all his resourcefulness, Gondry doesn’t have Resnais’ stylistic finesse, but this shouldn’t be surprising — the art of directing music videos is generally more about shifting strategies than about perfecting a single style. Still, it’s amazing how much he and Kaufman can do with their premise while carrying the audience along every step of the way. This is a movie about how difficult and painful relationships can be, even as it holds out some hope. The considerable invention and imagination used to tell this story are never brandished simply for their own sake: when a beach cottage starts to crumble before our eyes we immediately understand that what we’re watching is symbolic rather than literal, though the point isn’t belabored. The characters we see ring true, even though they never show much complexity, and the characters we don’t see (especially a woman Joel lived with before meeting Clementine) or only barely see (Howard’s wife, Joel’s friends) aren’t missed. This exquisite sense of proportion — concerning characters with no sense of proportion — ultimately carries the film, creating a kind of tacit complicity between script, filmmakers, and audience.