Jonathan Rosenbaum

Written for MUBI in October 2020.

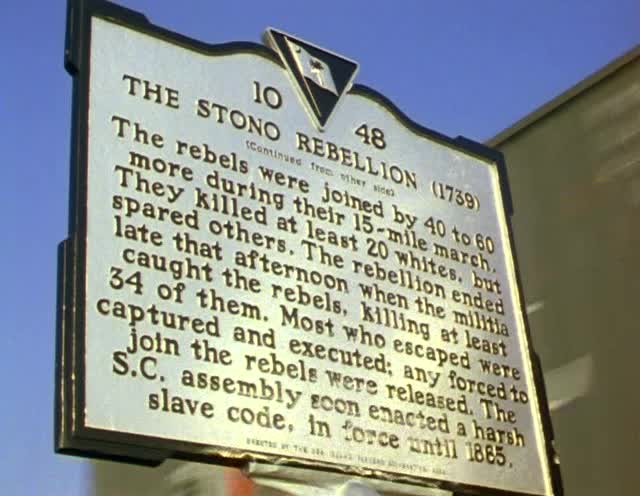

Let’s start with the title — a shotgun marriage between two omnipresent yet far from equally featured players in these unremarked, meditative spaces: an abstract impulse that supposedly keeps our American republic healthy and vital (while producing a lot of junk along with more helpful items) and a concrete force softly caresses everything in its path, keeping us alive and alert. More specifically, an encounter between the cause of many of the deaths that are being commemorated here — especially those relating to the genocide of Native Americans and many of the massacres occasioned by slave revolts and labor protests — and what D.W. Griffith lamented he found missing from modern cinema, the wind in the trees, found in the vicinity of most of the dozens of gravesites visited.

Arguably, according to the poetic rhetoric proposed by this 58-minute film of 2007, beautifully restored by Mark Rance, these diverse and scattered gravesites — hidden in the woods or identified by plaques on busy highways or next to prominent buildings in towns or cities — belong to heroes rather than martyrs, yet also to moving air more than what we usually recognize today as history. None the less, they trace significant portions of a chronological history of a given (or, rather, taken) territory, drawn mainly from Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of the United States, and a topography covering much of the same land mass, visited by Gianvito with his 16-millimeter sound camera.

After an epigraph by Claire Spark Loeb (“The long memory is the most radical idea in America”), we begin with the sound of “Kiowa Ghost Dance No. 12,” “Recorded July/August 1894,” and an onscreen phonetic transcription of this chant followed by a translation: “I am mashing the berries….They say travelers are coming on the march….I stir (the berries) around… I take them up with a spoon of buffalo horn.…And I carry them (to the strangers).”

A sense of remoteness inevitably gives rise to some unanswered questions. Are the arriving strangers motivated by profit (and not by the profit of berries) when they turn the natives into ghosts? Presumably or at least possibly, but the film doesn’t say. And the earliest grave site included in the film, presented soon afterwards–that of “Anne Marbury Hutchinson… [a] courageous exponent of civil liberty and religious toleration” killed by Native Americans in East Chester, New York in 1643, apparently for being in the wrong place at the wrong time — predates the invention of America and doesn’t relate to the profit motive in any obvious way. Yet this is only to suggest that what we don’t know about these lives is every bit as important to the film’s poetics as their presumed status of being politically exemplary. Clarity and mystery are Gianvito’s dialectical concerns, a duality also reflected in his title.

Bearing witness to ignored or forgotten facts and teaching us history lessons about them are the principal activities of his films. The Mad Songs Of Fernanda Hussein (2001), set in New Mexico during the first Gulf War, opens with a quotation from Cesare Pavese that could perhaps introduce all the others: “Everywhere there is a pool of blood that we step into without knowing it.”

Mad Songs’ epic length (168 minutes) and splintered narrative (like The Best Years of Our Lives, it has three stories to tell) probably contributed to its limited exposure, and comparable strictures have marginalized Gianvito’s documentary diptych For Example, The Philippines, consisting of Vapor Trail (Clark) (2010, 264 minutes) and Wake (Subic)(216, 277 minutes). By virtue of running less than an hour while taking in the full breadth of American history and much of its geography, Profit Motive and the Whispering Wind, which followed Mad Songs, has had a far easier time gaining a public reception, and the same can already be said for this year’s 96-minute Her Socialist Smile, about the politics of Helen Keller, on the heels of For Example, The Philippines. In both cases, it’s the shorter and more experimental works that have become more popular.

***

One could argue that the filmmaking team of Jean-Marie Straub and the late Danièle Huillet, recently highlighted on MUBI, is the key influence. (“Few other living filmmakers have mattered more to me in recent years,” Gianvito wrote in his Profit Motive shooting diary in October 2006, after learning of Huillet’s death.) Whenever the wind seems “angry,” I’m reminded of the violent chop of water at the beginning of the last shot of Straub -Huillet’s Too Early, Too Late (1981). But their films are almost invariably based on recitations of published texts in relation to natural settings, whereas here it is the gravesites and their own inscriptions that “speak”: Gianvito’s activity is to listen and see, not to repeat, transcribe, or represent. The presence of certain sites and locations is elicited and our virtual presence at those same spaces is solicited so that these shared presences might commingle in some fashion.

The ways and the degrees that they commingle — physically, spiritually, pedagogically, meaningfully — is left up to us, although the film’s title offers a couple of guidelines. That Gianvito’s interests are formal as well as didactic is suggested by the very brief passages of animation inserted into the film. As Gianvito explained in an interview with critic Michael Sicinski in the Canadian quarterly Cinema Scope, “There was early on the feeling of structurally needing another element, the taste of another ingredient. I wanted to reference capitalism but in the simplest way—focusing on physical gestures of commerce. These small gestures have a major impact on reality. And I wanted to render these hands via my own hand through drawing. Not that anyone need know, but the imagery is a stylization of brief moments from Treasure of the Sierra Madre (1948), Eclipse (1962), and Greed (1924), and is inserted more or less with historical connections, such as the 1848 California Gold Rush and the 1929 stock market crash. While these segments total less than a minute of the film, I felt the desire to disrupt the spell, if you will. The insertion of the trading floor clip, for instance, contrasts the serenity of the primary material with the animal ferocity in the money pit.”

The ordering of the gravesites is mostly chronological, but some resulting juxtapositions have their own stories to tell. The graves of two famous American rebels, John Brown (1800-1859) and Henry David Thoreau (1817-1862), are seen successively in two collective plots: Brown buried alongside a dozen of his followers, including two sons, and Thoreau in a family plot alongside five relatives. Other linkages include Lorraine Hansberry (author of A Raisin in the Sun) with Malcolm X and Upton Sinclair with John Dos Passos. Yet in a way, many of the most memorable graves that we encounter paradoxically belong to those we never heard of before. A rare intertitle informs us that the cofounder and first leader of the first national labor union in the U.S., The Knights of Labor, was buried in Philadelphia in 1869, but in 1951 was re-interred along with 65,000 others in nearby Mount Peace cemetery, and his remains now reside in an unmarked plot.