Written for the Kino Lorber Blu-Ray of this film, released in September 2019. — J.R.

Let me start with a confession about the ways that both fashion and one’s age can affect one’s taste. My first acquaintance with writer-director Claude Sautet (1924-2000) came when I was a hippie and cinephile in my late 20s living in Paris in the early ‘70s, a follower of Cahiers du Cinéma in my viewing preferences more than a follower of its leading monthly competitor, Positif, although I usually purchased both magazines. Back then, Sautet’s The Things of Life (1970), and César and Rosalie (1972) struck me as the epitome of well-crafted, genteel yuppie navel gazing, especially for what I took to be their uncritical embrace of the upper middle class. He was clearly a skilled director of actors, but the overall whiff of his milieu seemed complacent to a fault. Consequently, I steered clear of his 1974 Vincent, Francois, Paul and the Others, one of his biggest hits, and when, five years later, back in the U.S., I wrote an article about Chantal Akerman, Jean-Luc Godard, and the team of Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet for the mainstream and middlebrow American Film, I was mortified when my editors condescendingly changed my title to “Jean-Luc, Chantal, Danièle, Jean-Marie, and the Others,” which led Akerman herself to reproach me for the piece, assuming that I’d dreamed up that title myself.

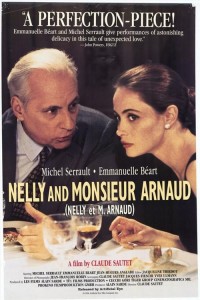

My second acquaintance with Sautet’s work came during my extended stint (1987-2008) as film critic for the Chicago Reader, when I gave mixed reviews to his A Few Days with Me (1988) and Un coeur en hiver(1991, A Heart in Winter), a pan to an American remake of The Things of Life called Intersection(1994), a sympathetic review to the belated American release of Sautet’s early and uncharacteristic gangster film Classe tous risques (1960), and a rave to the 1995 rerelease of Georges Franju’s 1960 Eyes Without a Face, which Sautet cowrote. And then I saw the masterful Nelly and Monsieur Arnaud (1995), Sautet’s final film, the following year, which finally made me a belated and enthusiastic convert. Suddenly what I had regarded previously as blandness and complacency now seemed like nuance and delicacy—an attentiveness towards the subtle vibrations between people in their daily interactions.

I’ve changed my tune in other respects as well, finding myself more sympathetic in some ways to latter-day Positif (which devoted 13 pages to Nelly and Monsieur Arnaud) than to Cahiers (which gave the film a guarded if favorable two-page review), and I’ve recently been upgrading my estimation of Paul Mazursky in a similar fashion relating to questions of class and age.

Age indeed had (and still has) something to do with the changes in my perspective and perception, especially in relation to this film’s subject matter—the relationship between a 25-year-old Parisian woman (Emmanuelle Béart) deeply in debt and married to an unemployed layabout and Pierre Arnaud (Michel Serrault), a septuagenarian former judge and businessman. They meet by chance in a café where she’s sitting with an older friend, Jacqueline (Claire Nadeau), who spots him (he’s a former lover) and invites him over. When he hears about her debts while Jacqueline has briefly left to phone her husband, Arnaud offers to settle them, no strings attached. She politely refuses, yet when she returns home that day, she tells her husband Jerôme (Charles Berling) first that she accepted Arnaud’s offer and second that she’s leaving him, which she promptly does the next morning. When she meets Arnaud again to accept his check, he offers to hire her as a typist and editor for a memoir he’s writing about his experiences as a judge at a Polynesian outpost. (Spoilers ahead, for those who care.)

One’s stereotypical and generic expectation about all this, especially given the apparent French tolerance for relationships between older men and younger women, is that the mounting emotional intensity of Nelly and Arnaud’s somewhat flirtatious friendship and working relationship will eventually lead to an affair, but it never does. Nelly does have a short-lived affair with Arnaud’s editor (Jean-Hugues Anglade), which leads to some stresses in her dealings with Arnaud; but this movie never founders on the obvious. Instead, the film offers a veritable encyclopedia of actorly gestures that indicate what may or may not be taken as sexual come-ons between Nelly and all the various men she encounters.

And indeed, what transpires between Arnaud and Nelly is a long dance of flirtation that climaxes in a back massage and, much later, Arnaud watching her sleep in one of his spare rooms and their briefly holding hands when she wakes—two minimal climaxes with maximal impact that unexpectedly evoke Robert Bresson in their physicality. Shortly afterward, when the husband of his ex-wife (Françoise Brion) dies unexpectedly in Switzerland and she comes to him in Paris for solace, he makes a sudden decision to go with her on a long trip around the globe that will end in the American northwest to visit their grown son—thereby removing himself from a situation that would only exacerbate his passion for Nelly. In a way, Arnaud’s sudden rupture of his relationship with Nelly matches Nelly’s sudden decision to leave her husband, which Arnaud unknowingly inspired.

Moreover, unlike the tense, unconsummated sexual undercurrents between an artist (Michel Piccoli) and his beautiful nude model (again, Emmanuelle Béart), both of whom have separate sexual partners, in Jacques Rivette’s 1991 La belle noiseuse, the viewer’s investment in these undercurrents is never allowed to become voyeuristic—that is, subject to the voyeuristic gratifications of the male gaze.

If Sautet has a stylistic signature, this might be the micro-notation—behavioral tremors and incidental narrative bumps that can’t be justified as parts of the plot, but which guide us towards being more attentive to passing details. At the first meeting between Nelly and Arnaud, after Jacqueline leaves to phone her husband, we get two sterling examples: a waiter tries to serve them two ice creams until Arnaud says, “No, that’s not for us,” and a bit later Jacqueline returns to get the proper change for her call. Both interruptions are totally inessential to the film’s dramaturgy, yet they prime us for the sort of passing nuances that transpire when, say, a character isn’t sure whether another character’s comment should be taken professionally or personally, a matter of courtesy or a gesture of sincerity.

I was 53 in 1996 and today I’m 76, although I hasten to add that part of Sautet’s achievement is his uncommon sense of equity in dealing with his two characters who are half a century apart. This isn’t simply — or even complexly — just a matter of showing us what it means to be a septuagenarian; it’s just as much a matter of what it means to be a young woman dealing with an old man (as well as with others closer to her own age). The fact that Sautet didn’t call his film Nelly and Paul is part of his way of saying that this is also a film about etiquette, even though we come to realize that the similarities between the two principals — their particular forms of reticence and emotional distance, combined with their abrupt and volatile way of arriving at crucial decisions and their capacities to share secrets — are as important as their differences.

Arnaud has a complex and perhaps shady past, which the movie only partly sketches in. He’s estranged from his ex-wife and from his two grown children. And he occasionally meets with a mysterious former colleague, Dollabella, who may be blackmailing him — or, if we believe Arnaud, only thinks that he’s blackmailing his former partner when in fact he isn’t. (Dollabella is played by the ubiquitous and accomplished Anglo-American actor Michael Lonsdale, who’s worked for everyone from Rivette to Orson Welles to James Ivory to Joseph Losey. In this film he’s given a special, witty credit emblematic of his character and his career in general: “With the fugitive participation of Michael Lonsdale.”)

Despite its sketchiness, the film’s portrait of Arnaud carries a lot of weight and conviction, and though Arnaud is roughly the same age as he was when he made the film, Sautet treats Nelly every bit as fully and sympathetically. One never feels that she’s merely being presented to us through Arnaud’s eyes. Her character and life, like Arnaud’s, is suggestive — we’re given her dislike of her mother, for instance, but no clear reasons for it.

It’s one sign of Sautet’s success that, though he presents neither character as especially admirable or exceptional, he makes us care about them a great deal. Their dignity and mystery register the way the dignity and mystery of real people and real lives do — as cumulative masses of small observations. Novels generally do a better job of gathering and conveying these observations than movies, but this film’s an exception.

Jonathan Rosenbaum’s latest books are Cinematic Encounters: Interviews and Dialogues (2018) and Cinematic Encounters 2: Portraits and Polemics(2019). He maintains a website at jonathanrosenbaum.net.