My column for the Spanish monthly Caiman Cuadernos de Cine, submitted on July 25, 2019. — J.R

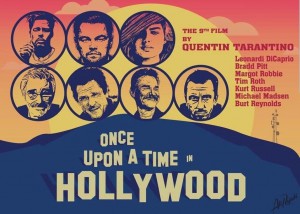

“The strongest argument for the unmaterialistic character of American life,” Mary McCarthy wrote in 1947, “is the fact that we tolerate conditions that are, from a materialistic point of view, intolerable.” Two kinds of doublethink fantasy emanating from this, both deriving from media tropes, can be found in the best and worst examples of recent American cinema that I saw in Chicago in July. These are, respectively, the four seasons of Crazy Ex-Girlfriend (2015-2019), a musical sitcom created by Rachel Bloom and Aline Brosh McKenna, which I saw alone on Netflix via my laptop, and Quintin Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, which I saw in 70mm at the Music Box with a full audience shortly afterwards. Significantly, deranged women are the basis of what I find exhilarating in the former and despicable in the latter.

The deranged woman in the first is a high-powered, neurotic Jewish lawyer (Bloom) in New York who rejects her firm’s partnership offer in order to move to a nondescript California suburb “four hours from the beach” to work for a mediocre firm and chase after a former boyfriend, whom she met at a camp as a teenager, meanwhile remaining in denial that her romantic obsession motivated her move. Her media-fed fears/fantasies/ruminations are expressed in song and dance. Forty-odd hours (in movie time) later, by the time she’s decided to forego any romantic relationship in order to overcome her hangups, she’s become friends with practically everyone in her orbit (including coworkers, ex-boyfriends, former romantic rivals, and neighbors), most of whom she’s infected with her obsessive behavior. What made me feel good about this, even without viewing companions, was that the immaterial issues honestly exposed and worked through resembled my own.

The deranged woman in the second movie — not at all its central figure, but for me the most pivotal one — is a fictionalized member of the Charles Manson hippie gang that in real life slaughtered actress Sharon Tate and four others in Roman Polanski’s Los Angeles house in the summer of 1969. In Tarantino’s fairy-tale version (spoilers follow), she gets obliterated with a flame thrower next door, in a swimming pool that belongs to a fictional cowboy and action star (Leonardo DiCaprio).Tarantino’s capacity to elicit cheers from the Music Box audience is his capacity to make people feel good about their enjoyment of a female hippie being burnt to a crisp, a trick he already used with Hitler in Inglourious Basterds. And what makes me feel terrible about this is that the immaterial issues dishonestly exposed and distorted to arrive at a “happy ending” resemble those of Donald Trump’s supporters.