Chapter Four of my book Movie Wars. It was originally written for Another Kind of Independence: Joe Dante and the Roger Corman Class of 1970, a critical collection coedited with Bill Krohn for the Locarno International Film Festival in 1999, which came out in French and Italian editions. –– J.R.

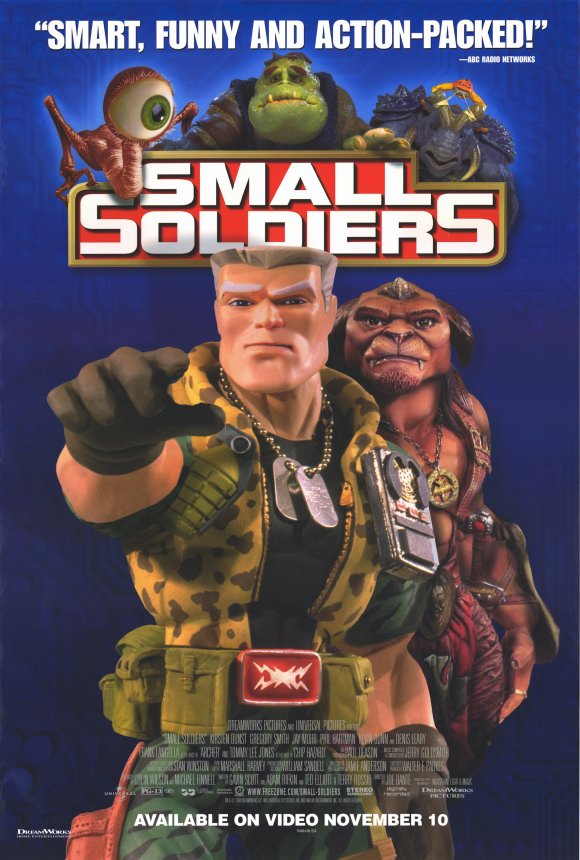

During the spring of 1998, not long before the American release of Small Soldiers, I happened upon “The Toys of Peace,” a wise and wicked tale by Saki included in A. S. Byatt’s recent collection, The Oxford Book of English Short Stories. Set in 1914, it recounts the noble and doomed efforts of the hero to interest his two nephews, aged nine and ten, in “peace toys”: models of a municipal dustbin and the Manchester branch of the YWCA, lead figurines of John Stuart Mill, Robert Raikes (the founder of Sunday schools), a sanitary inspector, and a district councillor. Forty minutes later, he looks in on the boys and finds that they’ve converted these objects into war toys: the municipal dustbin punctured with holes to accommodate the muzzles of imaginary cannons, Mill dipped in red ink to approximate an eighteenth‐century French colonel, with a grisly game plan mapped out to yield a maximum amount of bloodshed, including the remainder of the red ink splashed against the side of the YWCA building.

A mordant rejoinder to PC child rearing in 1914 England, Saki’s story testifies to the long-standing lure of make‐believe war to boys. Even more wicked and wise in some ways is Joe Dante’s Small Soldiers — a trenchant satire rude enough to suggest that some of the make-believe wars boys like to play turn out to be the real ones, including those in Vietnam and the Persian Gulf. The sentiments and fabrications underlying such escapades, as this movie sees it, are not so different from those underlying the games little boys play. This is especially true for civilian spectators who watch the battles from afar, accepting the mise en scène of newscasters and governments the same way that kids accept the game plans of toy manufacturers. But it also applies to some of the participants — the eager enlistees programmed by movies to see warfare as a glorified form of kicking butt. Garry Wills’s recent book, John Wayne’s America, hypothesizes that it was our fantasies about a movie star that got us into Vietnam in the first place. And couldn’t one argue that the two most successful American exports, movies and weapons, are both aggressive, fantasy-driven toys?

Small Soldiers opened in the United States in early July 1998, only two weeks prior to the release of Saving Private Ryan — a feature from the same Hollywood studio, DreamWorks, and directed by the man, Steven Spielberg, who effectively produced Small Soldiers — adding pertinence to the satire for anyone who cared to connect it with contemporary reality. To my way of thinking, Spielberg’s film represented a sophisticated form of warmongering, motored by clever, mainstream adaptations of practically every war film he’d ever seen; yet although his own discourse was every bit as cross‐referenced to other war films as Dante’s, this fact seemed far from apparent to the American press, which applauded Spielberg’s film precisely for its freshness and originality. Spielberg drew on second‐degree memories of All Quiet on the Western Front, Fuller’s war films, Kubrick’s war films, The Bridge on the River Kwai, third‐degree memories of John Ford’s war films, and many others — complete with little kernels of wisdom culled from each of these sources — while Small Soldiers parodied The Dirty Dozen and Apocalypse Now, among others. But the same critical establishment that deemed Small Soldiers both old hat and commercially crass, a remake of either Gremlins or Toy Story (or, in some cases, improbably both) motivated by simple greed, declared Saving Private Ryan to be brand-new and morally enlightening. The impact of the extreme violence of the Normandy Beach landing near the beginning silenced criticism in the same way that shouting can sometimes win an argument.

In short, the media profiles accorded these two releases were so radically different that the relevance of Dante’s film to Spielberg’s went virtually unnoticed. As far as most of the public was concerned, Small Soldiers was anything but an auteur film: the name “Joe Dante,” barely known in the first place among American filmgoers, was given so little emphasis in the film’s advance publicity that I failed to notice it myself and came very close to missing the Chicago press screening, even though I’ve been a passionate fan of Dante’s work at least since Gremlins. One way of partially accounting for this confusion was the deceptive nature of the ads — which I was later surprised to discover Dante had approved, perhaps as one way of negotiating and rationalizing his ambiguous alliance with the movie’s intricate tie‐ins with Burger King and the sale of various war toys. These ads foregrounded the toy soldiers known as the Commando Elite as if they were the movie’s unironic heroes rather than its pathetically programmed comic villains, falsely equating the movie’s essence with the crassness of Commando Elite’s manufacturer in the movie, known as Globotech. Until I noted in the ads’ fine print that Dante was the director, I came close to skipping the film myself thanks to this cheesy promo.

But don’t we all tend to lay critical grids over most films before we see them? A year or so ago I discovered in The Realist, Paul Krassner’s humor magazine, that the Chinese title of Oliver Stone’s Nixon was The Big Liar — which led me to speculate that if Stone had had the balls to give his movie that title in English, I probably would have hated it less. (I also have to admit that the aura of hushed respect surrounding Saving Private Ryan already made me approach it with some suspicion; for that matter, I’m wary of trusting the rhetoric of any director who chooses to begin and end a picture with the waving of an American flag — even a somewhat grey and tarnished American flag, as in this case, still sounds a note of sanctity.)

Perceived almost exclusively as a summer release for small children with multiple commercial tie‐ins, Small Soldiers was for the most part reviewed as such, and even though the two multiplex audiences I saw it with in Chicago — as well as the thousands of spectators at the outdoor piazza screening of the Locarno International Film Festival on August 7, 1998, a month after its U.S. opening, where it showed on a double bill with There’s Something About Mary — appeared to fully understand and appreciate it as a satire, the same appreciation in the U.S. media was at best scattered, perhaps because the ads spoke louder than the movie itself. (This is often the case with high-profile studio releases. Austin Powers: The Spy Who Shagged Me, which had a production budget of $35 million, was said to have an advertising budget of between $35 and $40 million.)

By contrast, the same media perceived Saving Private Ryan almost immediately as a serious art film; like Schindler’s List and Amistad, it was earmarked, long before any reviewers saw it, as a prestige item, a highly personal project, and consequently a brave commercial risk on the part of both Spielberg and DreamWorks. The fact that The New Yorker advertised a promotional interview with Spielberg on its cover by describing Saving Private Ryan as the film “to end all wars” was emblematic of the responses to the film elsewhere. Reviewers found it to be both serious and adult — further evidence of Spielberg’s growing maturity as a filmmaker, and a far cry from the money-grubbing cynicism and exploitative nature of something like Small Soldiers, which many of the most influential American film critics criticized for its violence, hypocrisy, and capacity to traumatize small children. No such criticism was waged against Saving Private Ryan because the much more graphic violence of the Normandy Beach sequence was taken to be a healthy jolt of reality, traumatizing only in a favorable sense by shocking the (supposedly adult) audience into a perception of the truth.

A characteristic phrase from New York magazine’s capsule review by David Denby — the film critic who can be counted on most regularly to express American doublethink with the least amount of self-consciousness — is the assertion that Saving Private Ryan “blows every other World War II film out of the water.” The use of a violent military metaphor to justify a supposedly pacifist or at least semipacifist war film should be connected ideologically and syntactically with The New Yorker’s previously cited cover blurb — i.e., “the film to end all wars that blows every other World War II film out of the water” — in order to understand more precisely the sort of hypocrisy that Dante’s film exposes.

But I don’t mean to suggest that the dismissal of Dante’s work was exclusively the consequence of American publicity. An appreciation of the ethical force of Small Soldiers depends not only on a recognition of Joe Dante as a particular kind of satirist, but also on a sharing of certain generational attitudes, as well as on the timing of the release of Saving Private Ryan, which gave Dante’s film a pointed relevance for me. Put somewhat differently, Small Soldiers thrives on its contextual references whereas Saving Private Ryan succeeds with audiences only when its own contextual references are overlooked. The media was inattentive to the references to other war movies in both cases because these went against the critical profiles these films were supposed to have — crass business motives in the case of Small Soldiers, heartfelt reflections of real-life experiences in the case of Saving Private Ryan.

The essential auteur of Small Soldiers was perceived by many American spectators to be Burger King, a not-unreasonable assumption given the film’s promotional tie-in deals, not to mention the fact that, as I eventually discovered from Dante himself, Burger King had the final cut. In Locarno, the only hint of a tie-in or promotional gimmick came with the free hair gel handed out to spectators as a joke in conjunction with There’s Something About Mary, so audiences were freer to respond to the movie on its own terms.

If Burger King indeed qualifies as the film’s auteur and Dante is merely its struggling metteur en scène, Small Soldiers can indeed be read as hypocritical; if the movie exists mainly to sell war toys and Dante can only work in the margins of this project by ridiculing selling war toys — and selling, buying, and consuming wars — then the whole enterprise has to be regarded as a machine turned against itself. So the question of how adept some critics were in screening out the ridicule has to be joined with the question of how defenders such as myself managed to screen out Burger King’s ad copy. In the final analysis, the heart of the matter is the question of what a movie consists of — a viewing experience or the central object in a marketing campaign. Saving Private Ryan was mainly treated as the former and Small Soldiers the latter, which accounts in part not only for the discrepancy between the two responses but also for the overall failure of the press to perceive any meaningful relationship between the two movies.

The following remarks are an attempt to chart that discrepancy and failure via my own particular reading of Small Soldiers.

***

Beginning with a TV commercial for Globotech, a huge conglomerate that boasts converting weaponry into peaceful uses — “beating with two toy designers working for his latest acquisition, Heartland Play Systems. One of these designers, nerdy Irwin (David Cross) — a rough equivalent of Saki’s idealist hero — believes in making educational, non-violent toys and has come up with a blueprint for benign, noble monsters known as the Gorgonites, creatures searching peacefully for Gorgon, their ancestral home. The other designer, hyper Larry (Jay Mohr), proposes the Commando Elite, a hard-ass squad of killer soldiers.

Scoffing at Irwin’s qualms about violence and rationalizing his own preferences in movie‐entertainment terms (“Don’t call it violence — call it action. Kids love action”), the CEO combines these two projects into a single line of products by designating the mainly white Commandos, miniature Schwarzeneggers and Van Dammes, as good, old-fashioned American destroyers and the Gorgonites as their multiracial targets and victims, then sends both designers off to produce high‐tech toys within six months. Eager to please his new boss, Larry filches Irwin’s computer password and with it manages to acquire a microchip from the U.S. Defense Department, thereby empowering his Commandos with all the “action” they need.

When an early shipment of Commandos and Gorgonites is getting trucked through a small town in Ohio, a rebellious teenager named Alan (Gregory Smith), minding his father’s New Age toy store, the Inner Child, persuades the trucker (Dick Miller) to turn over one set of the new products on consignment, despite the fact that his father (Kevin Dunn) won’t stock war toys. Knowing that he can turn an easy buck by selling these toys on the sly while his father’s away at a seminar on small businesses, Alan represents another version of Larry and the CEO — let’s call it the entrepreneurial spirit — while his ineffectual father represents Irwin’s bumbling idealism. But once both Commandos and Gorgonites break out of their boxes and become engaged in a full-scale war — the Commandos programmed to search and destroy, the Gorgonites programmed to hide and eventually lose — the humans in Alan’s house and the family next door, including Christy (Kirsten Dunst), the girl Alan is pursuing — become caught in the crossfire and are forced to take sides. As the Commandos convert everyday domestic objects and appliances into weaponry, the grim undersides of consumer culture and kick‐ass ideology come together in riotous, carnivalesque splendor.

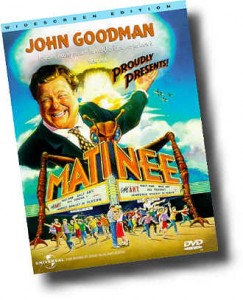

Dante’s satire doesn’t simply target war and warmongering but the everyday cultural violence that encompasses them, by which I mean the violence in pop culture as well as the violence of pop culture. With the possible exception of Inner Space, just about all of Dante’s best work is concerned with this cultural violence — cuddly Spielbergian pets in Gremlins; animated cartoons in “It’s a Good Life,” his segment of Twilight Zone—The Movie; TV in the finale of The Explorers and practically all of The Second Civil War (his prescient and neglected 1997 made‐for‐cable satire); xenophobia in The ’Burbs (despite the confusing ending); war fever in Matinee; corporate merchandising in Gremlins 2: The New Batch — and part of the exciting achievement of Small Soldiers is to combine all of these concerns into one streamlined statement.

Part of the kick of Dante’s cheerful scorn is that it takes on not only the more obvious targets like The Dirty Dozen (by employing members of the original cast to speak the voices of the Commandos), but also the less obvious ones, like Apocalypse Now — already perceived by many as an antiwar film and hence something of a sacred cow, even in the nineties — while adroitly exposing the innate childishness of the overblown epic and heroic stances in all of them. The self-importance of a supposedly “balanced” portrait like Patton (Richard Nixon’s favorite movie) is made to seem just as ludicrous as an imperialist adventure like Rambo, and the consumerist aspect of war films in general is kept in the foreground. This pointedly includes the hypocrisy of such flag-waving “history lessons” as the exploded and severed body parts in Saving Private Ryan, which are contrived simultaneously to sell tickets and to provide moral correctives to other war movies — though the movies being corrected often upped the violence quotient in their own eras with identical rationalizations and mixed motives.

An ironic syndrome: every time a director decides to make a war film more graphic in its violence than its predecessors, the argument seems to be, “This’ll make someone think twice about wanting to go to war,” but the apparent result is to make young male spectators even more eager to prove their mettle by diving into such bloodbaths. It’s another version of the syndrome described in the Saki story, and one that has understandably prompted some critics to claim that there’s no such thing as an antiwar war movie — though Spielberg, perennial exploitation apologist, has recently claimed the reverse, that “every war movie, good or bad, is an antiwar movie” (presumably including Sands of Iwo Jima and The Green Berets).

It might be argued that self‐deception is central to Spielberg’s achievements, as central to them as deceiving the public, because the two activities ultimately amount to the same thing. (Perhaps the apparent national desire to make Spielberg America’s official guru and poet laureate is predicated on an implicit understanding that he’s every bit as innocent about his motives as his audience — meaning that the audience knows it can safely remain innocent as long as he’s the grown‐up in charge.) Audiences wouldn’t be nearly so susceptible to accepting the seriousness of Spielberg’s “grown-up” projects if he weren’t so adept at doing con jobs on himself. It surely takes a combination of innocence and show-biz smarts to convince an audience to contemplate the Holocaust by first getting them to identify with a Nazi who enjoys going to ritzy nightclubs. The same mentality led Spielberg to tell Stephen Schiff in The New Yorker that he received an enormous amount of pleasure from giving money to charities without telling anyone — without telling anyone, that is, except Schiff and his millions of readers. That’s why the same man capable of claiming that Jaws was “his” Vietnam and that “every war movie, good or bad, is an antiwar movie” can convince other people that Saving Private Ryan is something other than one more recruiting film.

I’ll never forget the experience I had escorting the late Samuel Fuller, the much- decorated World War II hero and maverick filmmaker, to a multiplex screening of Full Metal Jacket, along with fellow critic Bill Krohn, in Santa Barbara thirteen years ago. Though Fuller courteously stayed with us to the end, he declared afterward that as far as he was concerned, it was another goddam recruiting film — that teenage boys who went to see Kubrick’s picture with their girlfriends would come out thinking that wartime combat was neat. Krohn and I were both somewhat flabbergasted by his response at the time, but in hindsight I think his point was irrefutable. There are still legitimate reasons for defending Full Metal Jacket, in my opinion — as a radical statement about what conditioning does to intelligence and personality, as a meditation on what the denial of femininity does to masculine definitions of civilization, as a deeply disturbing experiment in sprung and unsprung narrative, and no doubt as other things as well. But as a piece of propaganda against warfare, it remains specious and dubious, providing one more link in an endless chain of generic macho self-deceptions on the subject. And for all its technical flair, it might be argued that theprincipal achievement of Saving Private Ryan is to extend that sort of self-deception into the nineties.

***

Attempting to tabulate the forty-seven American reviews of Small Soldiers that I’ve read — a file that omits my own favorable review in the Chicago Reader, a few portions of which are recycled here — I note first of all that there’s an almost even split: twenty-two are unfavorable, eighteen are favorable, and seven are mixed. But what constitutes “favorable,” “unfavorable,” and “mixed” is largely a matter of interpretation and hardly means the same thing to any two reviewers. For instance, Eric Layton’s review for Entertainment Today, which I’ve identified as “mixed,” concludes, “To fully enjoy Small Soldiers, ignore its murky political messages and just enjoy the exceedingly special effects — sort of like you did during Armageddon.” Layton also argues, “Adam Rifkin’s script is ostensibly a meditation on the dangers of military technology and the senselessness of war, but Small Soldiers is so immersed in violence, all moralizing is rendered moot.” Rita Kempley voiced similar misgivings in the Washington Post, not because of the violence but because of the audience it addresses: although the movie’s “message is more sophisticated than it seems . . . the target audience of 6-, 7‐ and 8-year‐olds aren’t about to read anything into this rowdy, repetitious war game. And they certainly aren’t going to notice the hypocrisy inherent in a movie built around the violent children’s entertainment it pretends to condemn.” But Steve Murray in the Atlanta Journal-Constitution based his own mixed reactions on finding the film too derivative of Toy Story, The Indian in the Cupboard, the made-for-TV feature Trilogy of Terror, and, most of all, Gremlins: “That 1984 flick was also directed by Joe Dante, but he can’t sue himself.”

Perhaps a more meaningful tabulation would be how many of the reviews perceived the film as satirical, at least in its intentions, regardless of whether they were favorable or not. My rough estimate is that about two-thirds did, though interestingly enough the third that didn’t included most of the reviews that appeared nationally and reached the largest number of readers, including, among others, those of Gene Siskel in the Chicago Tribune, Peter Travers in Rolling Stone, Joe Morgenstern in The Wall Street Journal, Peter Rainer in New Times, Leonard Klady in Variety, and David Ansen in Newsweek. And not even this imposing lineup includes the Chicago Tribune’s Michael Wilmington, who alluded to the film’s unfulfilled “satiric potential,” but only in relation to toys; Roger Ebert (both in the Chicago Sun-Times and syndicated elsewhere), who noted a “satirical purpose” only in the evisceration of a member of the Commando Elite by a lawn mower; Dennis Lim in the Village Voice, who saw the satire directed exclusively against capitalism; Kenneth Turin in the Los Angeles Times, who noted only that Dante “does bring sweetness and a sense of satiric comedy to the human relationships”; and Janet Maslin in The New York Times, who criticized the film for directing “well-deserved satire at the toy industry” at the beginning and then “forgetting” to include any more of it later. (It’s worth adding that Maslin’s “mixed” notice, in keeping with many of her reviews, echoes Variety by judging the film largely as a business venture; it begins, “Nothing beats a plaything when it comes to comandeering the attention of children, so Joe Dante’s Small Soldiers should have had the makings of a sure thing.” Many of the other reviews, for that matter, underline the degree to which, even outside trade publications, present-day film reviewing often conflates business judgments with aesthetic evaluations.) In short, none of these dozen reviewers gave the slightest indication that Small Soldiers had anything to say about war or war films, and because they set the tone of the film’s overall critical reception, the possible relevance of Dante’s film to Saving Private Ryan became a lot easier to miss.

Two recurring references in most of these reviews, especially the unfavorable ones, are to the late Phil Hartman, whose last screen performance is in the film, and to Toy Story, the Disney computer animation hit. Hartman, murdered by his girlfriend while the film was still in production, plays the hero’s next-door neighbor, a compulsive TV buff who at one point utters a memorable line to his wife —“World War II is my favorite war” — that one can easily imagine being attributed to Spielberg. Though the film is dedicated to Hartman in its closing credits (featuring a brief outtake of him as a tribute) and his role in the film is relatively minor, many reviewers were disturbed by his presence; one considered it an act of bad taste by DreamWorks to have released the film at all, and Travers in Rolling Stone structured his entire short review around the complaint that Small Soldiers was unworthy of Hartman’s talent.

Toy Story, by virtue of using toys as characters, was most frequently mentioned as a film that Small Soldiers either ripped off or tried unsuccessfully to emulate. The late Gene Siskel complained on the weekly TV show that he shared with Ebert that he expected something more “cutting edge” from Small Soldiers, like Toy Story — apparently thinking of the technology involved in that cartoon feature, without any reference to its content — and many other reviewers, including Ebert, decried Dante’s violence as harmful and disturbing to children, again in comparison to Toy Story. (On their TV show, they jointly concluded that the film was too dumb for adults and too violent for children, making it not worth seeing for anyone.) But the only cutting edges I can recall from that earlier movie are the ones used to gouge out the eyes of toy figures, perhaps because I find it difficult to isolate technology from what it’s being used for. I don’t have children of my own, but it’s hard for me to see how an exercise in good-natured, across-the-board ridicule of warmongering could traumatize the same kids who are packed off to enjoy the squeezed‐out eyes and severed limbs of Toy Story without qualm. One parent has assured me that the violence of Toy Story wasn’t perceived by his little boy as violence but rather as a visceral rush of images. It’s hard to know how to quarrel with this, but I would argue that just as kids are perfectly able to distinguish between animation and live action (which amounts to the usual defense of Toy Story as a harmless children’s movie), they’re also able to distinguish between toys and human beings. In any event, the subsequent wide popularity of Small Soldiers with small children on home video, which briefly encouraged DreamWorks to envision a sequel, hasn’t to the best of my knowledge — based on the experiences of various parents and babysitters I’ve spoken with — resulted in any traumas.

The strongest element of censure in the reviews by both Ebert and Klady is the charge of mean-‐spiritedness, which deserves to be examined in greater detail. Here are the most relevant passages from the two reviews:

EBERT: Small Soldiers is a family picture on the outside, and a mean, violent action picture on the inside. Since most of the violence happens to toys,

I guess we’re supposed to give it a pass, but I dunno: The toys are presented as individuals who can think for themselves, and there are believable heroes and villains among them. For smaller children, this could be a terrifying experience. . . .

In Small Soldiers, toys have unspeakable things happen to them, and many of them end up looking like horror props. Chip Hazard [a member of the Commando Elite] meets an especially gruesome end. What bothered me most about Small Soldiers is that it didn’t tell me where to stand or what attitude to adopt. In movies for adults, I like that quality.

But here is a movie being sold to kids, with a lot of toy tie‐ins and ads on the children’s TV channels. Below a certain age, they like to know what they can count on. When Barbie clones are being sliced and diced by a lawn mower, are they going to understand the satirical purpose?

KLADY (opening paragraph of review): The notion of technology running amok fuels Small Soldiers. When children’s action toys, implanted with faulty military microchips, begin to move, speak and learn, they turn on their human owners with a lethal vengeance. It’s an adult’s paranoid dream come to life, so setting it in a juvenile context may have inadvertently undone the foundation of the story. And while pic’s sense of a toy store turned upside-down, courtesy of dazzling f/x, will draw young viewers, ultimately the film’s mean-spiritedness and serious underpinnings will turn off its core audience. The result will be rapid commercial erosion and disappointing theatrical box office; ancillary movement, particularly on video, could provide the pic with a more vital afterlife.

In order to counter Ebert’s and Klady’s objections, some of the facts in their reviews need to be disputed: Klady’s claim that “the action toys . . . turn on their human owners with a lethal vengeance” obscures the facts that the targets of the Commando Elite are actually the Gorgonites, who are programmed to hide and to lose, and that the human “owners” of both toys are at risk only when they get in the way or shelter the Gorgonites. Similarly, Ebert’s description obscures the fact that many of the Gorgonites “[look] like horror props” from the outset, and this is what makes them the heroes of the film. Moreover, the affection expressed by the film toward these noble underdogs and the fear and derision expressed towards the Commando Elite, represented unambiguously as unthinking and merciless killing machines, provides precisely the moral positioning that Ebert finds absent — an indication both of “where to stand” and “what attitude to adopt,” though this clearly is an indication rather than a set of moral directives.

Given such faulty descriptions, the charge of mean‐spiritedness becomes comprehensible. The sense of recoil conveyed by both reviews suggests that a serious grappling with the issue of enjoying warfare as spectacle is indeed “mean-spirited” if the viewer’s own impulses in that direction become the target of the ridicule. And though Ebert is provocative enough to suggest that allowing the viewer a certain amount of moral freedom is commendable in a movie for adults but reprehensible in a movie for children, it might be argued that the only partially concealed moral directives and biases of Saving Private Ryan make Spielberg’s film in Ebert’s terms a film for children, not adults.

The fact that these reviewers and others didn’t perceive Dante’s efforts as satire about the consumption of war as spectacle or art is unfortunate but not entirely unprecedented. Dante’s major predecessor in American pop cinema, the late Frank Tashlin, was equally misunderstood in the United States. Tashlin’s own vision of cultural violence was grounded in animated cartoons — he began as a cartoonist and animator — but the objects of his satirical and parodic scorn were somewhat different, tied to what was most aggressive about American pop culture in the fifties: comic books (Artists and Models); Hollywood (Hollywood or Bust); rock ’n’ roll (The Girl Can’t Help It); advertising (Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter?); television (Rock‐a-Bye Baby); all kinds of media excess, sexual hysteria, loud colors, and gadgets (passim).

As a fan and aficionado of horror and SF movies as well as cartoons, Dante has a different spin on cultural aggression and what it consists of, but his fascination with the pop materials that he mocks and synthesizes rivals Tashlin’s, leading some commentators to conclude that he’s too invested in these materials to qualify as a satirist. Just as some critics found Tashlin too vulgar to qualify as a satirist of vulgarity, some critics today find Dante’s movies too violent to qualify as satires about violence. I would argue in both cases that the extreme stylization of both directors creates a sense of detachment about what they’re showing that is the true source of disturbance. Nothing is ever perceived as real in their comic fantasies, which means that viewers who want to participate are forced to reflect on their own reactions to what they’re watching, examine their own reflexes, and consider how much they’re the targets of what’s being satirized.

Small Soldiers doesn’t represent the first time that Joe Dante has been misunderstood, nor, I suspect, will it be the last. His previous theatrical release in the United States, the 1993 Matinee, was about war fever, and reviewers who saw any connection between the Cuban missile crisis and the periodic eviscerations of Bagdad in the early nineties were few and far between. Though virtually all of Dante’s movies are about the ethics and ramifications of spectatorship, he prefers to keep a low profile within the studio system and works without a personal publicist — the most obvious reason why a good many reviewers resist treating him like an auteur.

No doubt part of the failure of many American critics to perceive Small Soldiers as satire can be attributed to the habit of perceiving satire strictly according to the Swiftian model — the contempt for humanity in general and the audience in particular that infects, for instance, Dr. Strangelove, Wag the Dog, and The Truman Show, all relative favorites with critics and other industry “insiders” who pride themselves on their “media savvy.” The character played by Ed Harris in The Truman Show epitomizes this self-regarding image — a deity in the clouds who understands what the audience needs and wants with the proper amount of lofty condescension; the fact that Harris was honored with an Academy Award nomination for this performance only underlines the flattery.

From this standpoint, one of the most elucidating as well as disconcerting aspects of The Second Civil War — the middle film in Dante’s war trilogy that started with Matinee, regrettably seen only on cable in the United States (though shown theatrically in Europe) — is the degree to which Dante refuses to show contempt for any of his human characters, no matter how monstrous and misconceived their behavior might be. The contradiction in The Second Civil War between the dangerous xenophobia of the policies of the governor (Beau Bridges) and the affection he expresses for both his Mexican mistress (Elizabeth Pena) and Mexican food may be blatantly hypocritical, but rather than heap scorn on this character, Dante actually appears to like him; in effect it’s only the xenophobia that gets fully ridiculed. A similar refusal to treat any characters as pure villains characterizes the work of Tashlin, and the generational attitude associated with Dante’s satire is part of Tashlin’s legacy. It’s a legacy of both skepticism about and distance from the complex joys and perils of spectatorship — a legacy suggesting that Tashlin’s origins as a cartoonist and Dante’s as a film critic may represent two versions of the same basic impulse.

Small children seemed to have a much easier time picking up the satiric message of Small Soldiers than many of this country’s most prestigious film critics, suggesting the problem that “noise” — represented in this case by advertising and Burger King tie-ins, both of which helped to occlude Dante’s creative input — presents in assessing movies. Or maybe a likelier reason that film critics missed the point is their desire to assent to Spielberg’s patriotic warmongering, which Small Soldiers exposes with cheerful derision.