Written for Cineaste (Winter 2018). — J.R.

Auteur Theory and My Son John

by James Morrison. New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2018.

190 pp. Hardcover: $75.00, Paperback: $19.95, and Ebook:

$17.95.

My admiration for and my demurrals about James Morrison’s brilliant monograph both begin on the first pages of his Introduction. He quotes the title subject of Mike Nichols: An American Master (2016) on the “froggy conspiracy” which elevates figures like Howard Hawks and Jerry Lewis at the expense of George Stevens, Billy Wilder, William Wyler, and Fred Zinnemann (“our greatest directors”), a statement that Morrison aptly compares to the vulgar parodies of existential beatniks in Stanley Donen’s Funny Face. Yet two pages later, when he calls Nichols “countable as one of the ‘auteurs’ who by common consent ushered in the New Hollywood,” Morrison seems to be indulging in aspects of the same parody, especially when one considers that he’s decided to suppress the information that Mike Nichols: An American Master is the work of a genuine auteur, Elaine May (coincidentally, Donen’s current partner), and not only because, unlike Nichols, she functions as a film writer as well as a film director. I presume that Morrison chose to suppress May’s involvement in this glib claptrap because it complicates his argument, especially when he goes on to show that Nichols’ tirade is seemingly bolstered by May’s montage of dumb quotes from Bosley Crowther about Bonnie and Clyde, and from Pauline Kael and Renata Adler about 2001, constituting what Morrison rightly calls “a slam against film criticism as such”. Even though being an auteur (however brilliant) and skewering film criticism (however crassly) are very different matters, it suits Morrison’s sense of polemical decorum to elevate Nichols as an auteur, even with suitable scare quotes, at the expense of his erstwhile sparring partner. In May’s case as well as his own, it all depends on whom you think you’re addressing.

Having spent a delightful evening with May in 2010, I can attest that, in spite of her cordiality due to my enthusiasm for her work, her lack of any serious interest in film criticism was unmistakable. And Morrison clearly is addressing his own remarks to academia, not to the mainstream arena where most filmmakers like May and Donen live and operate — although it’s to his credit that his superb history and analysis of auteurist criticism, which forms the first half of this book, is sufficiently far-ranging to include the now largely forgotten nonacademic New York Film Bulletin in the early 60s. Lamentably, it doesn’t include the three issues of the more intellectual and literary New York auteurist journal Moviegoer from the same period, which featured such writers as Susan Sontag and Paul Goodman as well as Andrew Sarris and Roger Greenspun, not to mention a very thoughtful defense of My Son John by Donald Phelps against much of the attack of Robert Warshow. Given Morrison’s unfriendly review of Gilberto Perez’s The Material Ghost in Screen, this might suggest a bias against literary auteurists in general, apart from Robin Wood, were it not for the fact that Morrison himself, a fiction writer as well as a critic, writes with some literary distinction. (Example: “The [French] auteurist model was essentially antinarrative, defined by the lyric strophe, the poetic intuition, the soaring crescendo or the dying fall, the rhythmic creation of beauty.”)

Where Morrison’s analysis of auteurist thinking becomes especially acute and valuable is in the ways he distinguishes between the Surrealism-inflected “Eureka!” reflexes of the French critics looking for poetic explosions and modernist social critiques amidst flaws and compromises and the more conservative and idealistic habits of American critics such as Andrew Sarris looking for overall unity and coherence, with André Bazin’s beliefs in realism and the “genius of the system” implicitly serving as a sort of relay between these positions. No less implicitly, though without ever saying so, Morrison also helps us to understand what distinguishes the modernism of Godard, Rivette, and Truffaut as filmmakers from the premodernism of Bogdanovich and the postmodernism of De Palma and Scorsese, based on their own auteurist groundings.

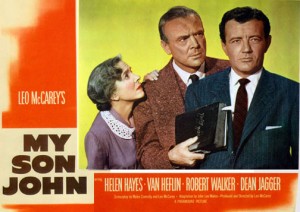

When it comes to outlining Leo McCarey’s characteristics as an auteur he is no less authoritative, especially when it comes to delineating the dynamics of individual performances as offset and propelled by McCarey’s mise-en-scene. He rightly focuses on Helen Hayes’ remarkable performance as Lucille Jefferson in My Son John as the film’s emotional center, even more than Robert Walker’s in the title role, although he seems bemused by a striking moment of her gestural pantomime in an early scene, correctly labeling that moment as a sign of her feisty independence from the family but not appearing to recognize it as a mocking parody of the mental instability she feels her doctor and husband are both assigning to her by urging her to take medication. (As long as I’m cataloguing minor grouses, the only actual error in the book that I spotted is Morrison misidentifying “a murder shown in full blood-and-gore detail” in Once Upon a Honeymoon as “the assassination of an American double agent”—an event that occurs offscreen—rather than a Polish general.)

Having first seen My Son John when it came out, at the tender age of nine, when I only dimly understood what it was saying and doing, and then having rediscovered it many times — first as a deranged Cold War fantasy, then as a flawed masterpiece about family dysfunction, and eventually as both — I’ve often felt frustrated about not knowing more about the original script, the sort of changes necessitated by Robert Walker’s sudden death in the midst of shooting, and the paranoid conditions underlying both the theme — an all-American couple discovering that their son (Walker) is a Communist spy — and the film’s strained completion (including the fact that Walker’s death was initially hidden from the public). Morrison’s research answers most of my queries, though not how McCarey and/or Paramount managed to conceal the death as long as they did (nor how long that stretch was). At most, I could glean from Serge Daney and Louis Skorecki’s interview with McCarey in Cahiers du Cinéma that John’s death was necessitated by Walker’s and that McCarey’s decision to dub his dying words himself was motivated by all the secrecy.

My own sense of McCarey’s contradictory singularity as an auteur is that he’s both an ideological primitive and a highly sophisticated dialectician who makes the comedy of embarrassment and the tragedy of excruciation virtually interchangeable and equally incapable of achieving any resolution. This is apparent not only in the determination to make Dean Jagger’s Dan Jefferson, the father in My Son John, a bumbling fool even while espousing McCarey’s most cherished, simplistic notions about family, democracy, and anticommunism, and it is no less evident in his abortive final feature Satan Never Sleeps, where he seeks to derive both comedy and tragedy from the sexual attraction of a priest (a miscast William Holden) for a Chinese girl (Francis Nuyen) who’s innocently smitten with him. McCarey ultimately quit this film in disgust after Holden refused to let his character die in a suicidal escape, which presumably would have contradicted McCarey’s Catholic faith as decisively as Jagger’s idiocy in John contradicts the writer-director’s patriotism. As Morrison observes, “Dan Jefferson is the most fully sketched father in McCarey’s films and the least sympathetic by far, though a conflicted attitude toward him ultimately circumscribes the film’s most pressing critical problems.” One might add that Gary Cooper’s far more sympathetic (if still quite irritating) title character and father in Good Sam (1948), another troubled self-portrait — and a film I rank much more highly than Morrison does — offers many of the same fascinating conundrums.

As a master of disbelief as well as belief, McCarey is as much of a dialectician as Carl Dreyer — a claim supported by Morrison’s apt if unexpected comparison of John’s closing image with the final shot of Ordet. Indeed, McCarey manages to make Walker’s John in the film’s first half so compelling that it becomes impossible to believe that his scripted conversion could have been made plausible even if the actor had lived, in spite of Walker’s resourcefulness (which includes even a hint of gayness as a carryover from his performance as Bruno in Strangers on a Train, portions of which McCarey recycled in his inept conclusion). The degree to which an FBI agent named Steadman (Van Heflin) assumes the role of father-confessor rather than a bumbling priest (Frank McHugh) was Warshow’s most valid objection to the film’s muddle-headedness, and this confirms McCarey’s impulses to sabotage his own ideological agenda.

Within such a context, Hayes’ tremulous Lucille functions as the battleground between the dialectic of Dan’s all-American stupidity and John’s poker-faced Communism, even if McCarey couldn’t really imagine what that Communism might consist of, and thus her separate scenes with Jagger and Walker are central to the film’s complex, ambiguous power. Yet Morrison’s analysis reaches its own giddy highpoint, in auteurist terms, when it allow us to see John’s bottled-up distaste for Dan as an echo of Ruggles’/Charles Laughton’s repressed disapproval of his hick employers in Ruggles of Red Gap, and, in the following paragraph, persuasively links Dan bopping John on the head with a Bible, causing him to fall over a table — a moment usually seen as noncomic — as a slapstick maneuver traceable back to Laurel and Hardy, a team McCarey invented as well as directed.

— JONATHAN ROSENBAUM