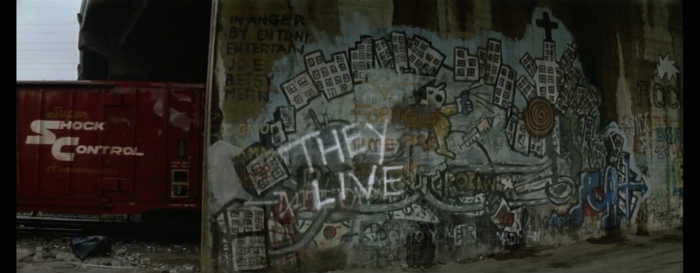

This appeared in the November 18, 1988 Chicago Reader. I’d probably rank this film higher now. — J.R.

THEY LIVE

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by John Carpenter

Written by “Frank Armitage” (John Carpenter)

With Roddy Piper, Keith David, Meg Foster, George “Buck” Flower, Peter Jason, and Raymond St. Jacques.

John Carpenter has managed to remain one of the few genuinely personal writer-directors left in genre moviemaking, having returned to relatively low-budget features with last year’s Prince of Darkness after the debacle of Big Trouble in Little China. From his clean ‘Scope compositions to his throbbing minimalist scores, he projects a simplicity of conception and a usually deft approach to story telling and straight-ahead action that are both refreshing and reassuring in an era of filmmaking when these modest virtues can no longer be taken for granted. As a disciple of Howard Hawks, he might even be said to preserve a scaled-down version of some of the familiar Hawks trademarks: cranky individualist heroes, flaky male/female relationships, camaraderie among professionals, confined spaces, and usually clear lines of demarcation between friends and foes.

All of these qualities are present to some degree in They Live, a paranoid science-fiction thriller about alien invaders loosely based on a short story by Ray Nelson. Read more

From the July 1982 issue of Omni; reprinted in Cinematic Encounters: Interviews and Dialogues (2018). As with all the other commissioned pieces I wrote for the Arts section of that magazine, this originally ran without a title; I’ve also done a light edit on this version. Another version of this article appeared in Cahiers du Cinema, with a different title (if memory serves, this was called “Beware of Imitations”).

While I was living in Europe in the 70s, I managed to watch portions of the shooting of films by Robert Bresson (Four Nights of a Dreamer), Alain Resnais (Stavisky…), and Jacques Rivette (Duelle and Noroit), but my trip to Alaska and British Columbia in December 1981 to watch a little bit of the shooting of John Carpenter’s The Thing was surely my most elaborate on-location visit, even though what I actually saw was much briefer in this case — hardly any more than an hour or two at most. And I didn’t even get to speak to Carpenter during my visit; absurdly enough, by arrangement with the film’s publicist, the interview in this piece was conducted over the phone several days later, with Carpenter calling me from Hollywood, after I returned to Hoboken, making the cassette recorder I had carried on my trip completely unnecessary and some portions of this piece necessarily deceitful. Read more

A 2018 column for Caimán Cuadernos de Cine, submitted shortly before the New Year. — J.R.

Shortly before Christmas, I flew from Chicago to New York in order to witness Elaine May on Broadway as she powerfully and persuasively played the lead role in a two-act Kenneth Lonergen play, The Waverly Gallery, about her character’s encroaching senility and memory loss. It’s as if May, now pushing 87, asked herself, “What terrifies me more than anything else?” and then decided to enact, embody, and exorcise that terrifying condition eight times a week, playing a compulsive talker who is gradually losing both her mind and her ability to communicate with her daughter, her son-in-law, her grandson, and the only new painter in her Greenwich Village gallery, all of whom eventually give up on her even when they start to share some of her irrationality and incoherence.

Although I usually process May’s genius more in terms of cinema than in terms of theater, perceiving the grim darkness of her performance here in relation to the tragic finality of her feature Mikey and Nicky, this also makes an intriguing bookend with An Evening with Mike Nichols and Elaine May, which ran on Broadway 58 years ago under Arthur Penn’s direction and featured a certain amount of improvisation. Read more

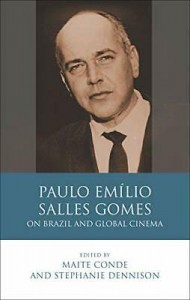

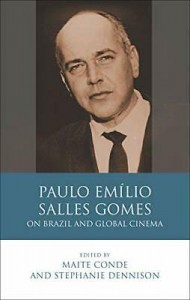

For Cineaste, Spring 2020. — J.R.

Paulo Emílio Salles Gomes

On Brazil and Global Cinema

Edited by Maite Conde and Stephanie Dennison.

Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 2018, 242 pp.,

Hardcover: $199.99, Kindle: $64.60, Paperback (from

University of Chicago Press): $68.00

Brazilian critic, film historian, and teacher Paulo Emílio Salles Gomes (1916-77) is principally known outside of Brazil as P.E. Salles Gomes, the author of the 1957 book Jean Vigo — not only a definitive biography, essential to Vigo’s posthumous rediscovery, first published in France (and translated from French to English in the early 1970s by the author), but also clearly one of the first major critical biographies of any filmmaker in any language. The editors of this volume, however, usually refer to him simply as Paulo Emílio, and picking up on their friendly Brazilian etiquette, I will follow suit.

$68.00 is an outrageous price for a paperback book less than 300 pages long, suggesting a volume intended only for well-funded libraries and professors with institutional perks to spare. But I’m also obliged to report that this first collection by a major and widely neglected figure in film studies redirects my thoughts about cinema like few other recent books. Read more

The Heart of the World****

Directed and written by Guy Maddin

With Leslie Bais, Caelum Vatnsdal, Shaun Balbar, and Hryhory Yulyanovitch Klymkyiev.

It lasts only about seven minutes, making it roughly comparable in length to a Bugs Bunny cartoon, but Guy Maddin’s The Heart of the World — which opens this week at Landmark’s Century Centre with The Last Resort — conjures up a universe so vast and wacky that anyone can get lost in it. Like any film released in February, it has a very poor chance of getting an Oscar, because the Academy Awards nominators — who know better than anyone how such honors are designed to sell more than evaluate — don’t want to consider many candidates released before Thanksgiving. But for my money it’s better than any of the current best-feature nominees. It has more action and is quite a bit funnier. I’d even call it inexhaustible.

Maddin’s movie premiered last September at the Toronto film festival, which had commissioned it as one of several “preludes” by leading Canadian filmmakers to run unannounced before the features, a series designed to celebrate the festival’s 25th anniversary. It was commonly regarded as the best film shown at this gala event, though I’m not sure I’d go quite that far. Read more

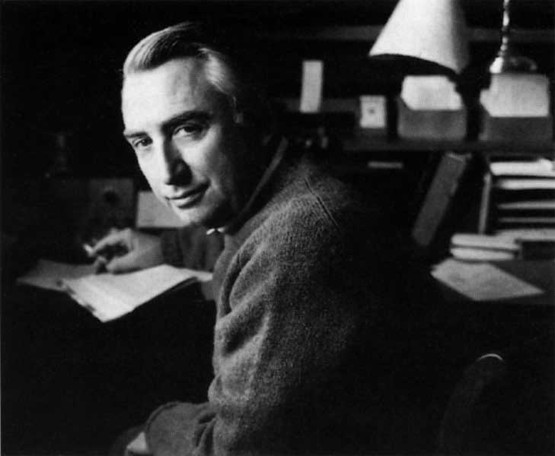

From Sight and Sound, Winter 1982/1983, and reprinted in my collection Placing Movies. It was initially commissioned by Peter Biskind for American Film, who decided not to run it and paid me a kill fee, so I sent it next to Penelope Houston, who accepted it without hesitation. Originally, this piece was designed to be run with my translation of a brief, early piece by Barthes (“Au Cinemascope,” originally published in Les Lettres Nouvelles, February 1954). To my frustration, after Sight and Sound secured the rights to run this piece, they wound up omitting it due to lack of space, but it has subsequently appeared online in at least two places: here and here (the latter on this site). — J.R.

One reason for looking at the late Roland Barthes’ writings about film is that we all tend to be much too specialized in the ways that we think about culture in general and movies in particular. Far from being a film specialist, Barthes could even be considered somewhat cinephobic (to coin a term), at least for a Frenchman. Speaking to Jacques Rivette and Michel Delahaye in 1963, he confessed, “I don’t go very often to the cinema, hardly once a week” — inadvertently revealing the French passion for movies that can infect even a relative nonbeliever. Read more

Written for the catalogue of Il Cinema Ritrovato in Bologna (June-July 2017). — J.R.

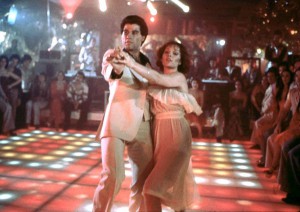

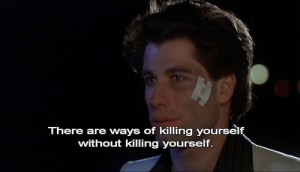

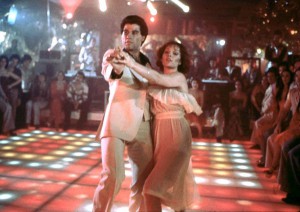

Dave Kehr has aptly described it as a “1977 update of Rebel Without a Cause” and a “small, solid film, made with craft if not resonance”. But it’s also a dance musical and the hit that catapulted John Travolta to stardom after a brief career in theater and on television (notably on Welcome Back, Kotter).

There’s a manic-depressive side to most musicals—a tendency to navigate mood swings from depression to exhilaration and back again–that’s observable in everything from Swing Time to The Band Wagon to La La Land. Saturday Night Fever takes that pattern to an unusual extreme in the way it oscillates between a view of Brooklyn’s Bay Ridge neighborhood as a version of hell on earth whose residents devote all their waking hours to humiliating one another and the heavenly, utopian lift and glory of dancing at one of its discotheques called 2001 Odyssey. Most people who fondly remember this movie are likely to focus on the latter and think less about the former, but it’s the relation between these two registers that gives the movie its energy.

The screenplay by Norman Wexler (Joe, Serpico, Mandingo) is derived from an article in New York magazine (“Tribal Rites of the New Saturday Night”) whose author, British rock critic Nik Cohn, admitted two decades later was more invented than observed. Read more

An essay commissioned by Masters of Cinema in the U.K. for their DVD of Fritz Lang’s Spione, released in 2005. This is reprinted in my collection Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia: Film Culture in Transition (University of Chicago, 2010). — J.R.

If Fritz Lang’s Die Nibelungen (1924) anticipates the pop mythologies of everything from Fantasia to Batman to Star Wars, his master spy thriller of four years later seems to usher in some of the romantic intrigues of Graham Greene, not to mention much of the paraphernalia of Ian Fleming, especially in their movie versions. No less suggestively, the employments of paranoia and conspiracy by less mainstream artists such as Jacques Rivette (Out 1) and Thomas Pynchon (Gravity’s Rainbow) seem rooted in the seductively coded messages, erotic intrigues, and multiple counter-plots of Spione.

One is also tempted to speak of Alfred Hitchcock, who certainly learned a trick or two from Lang —- though in this case the conceptual and stylistic differences may be more pertinent than the similarities. One could generalize by saying that Hitchcock is more interested in his heroes while Lang is more interested in his villains, and the different approaches of each director in soliciting or discouraging the viewer’s identification with his characters are equally striking, especially if one contrasts the German films of Lang with the American films of Hitchcock. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (February 27, 2004).

On February 12, 2018, Ken Jacobs sent me the following email:

Dear Jonathan,

I first came upon writing on STAR SPANGLED TO DEATH a week ago. Sorry.

Appreciate what you had to say except, naturally, for your take on my Muslim comment. So I must’ve failed to make clear my despising of all religions with their bloody track records. I go so far as to consider the to-do about Nazis overblown: a momentary political organization that, employing Ford up-to-date industrial methods, accomplished the actual near-fulfillment/”final solution” to 2 000 years of strenuous Christian degradation, torture and outright slaughter of Jews. “Race” had just been invented maybe a century earlier but murdering Jews was an enduring Christian project. (Nor were Nazis killing any other “race”.) A fact to remember about WW2: Christians murdered Jews. A land war coupled to a religious “war” and the war they were allowed to win by USA as long as they could keep costing the Soviets. Don’t get me started….

I’m remembering one line in the film about “a bedtime story gone amok”. That is my take on these force-fed beliefs given helpless children wired up to believe, needing to believe if they’re to survive (“no, you can’t run into traffic”).

Read more

From the Boston Phoenix (September 15, 1989). — J.R.

This enjoyable documentary about American comic books takes up a subject so fruitful and entertaining, it’s surprising no one has ever made such a film before. Canadian filmmaker Ron Mann — whose previous cultural investigations include feature-length documentaries about avant-garde jazz (Imagine the Sound) and North American poets who sing and chant their works (Poetry in Motion), and who is currently preparing a feature about the Twist — dives into his chosen turf with the zeal and affection of a voracious fan.

Starting out with the inception of comic books, in 1933, Mann gives us breezy surveys of the superheroes (such as Superman, Batman, and the Fantastic Four), EC Comics (which produced the best horror and sci-fi comics in the 50s and spawned the original version of Mad), the underground artists (such as Robert Crumb and Spain Rodrigues) who emerged in the 60s, and more recent figures such as Art Spiegelman, Sue Coe, and Lynda Barry, as well as the deliberations and operations of Raw, a contemporary publicatiin with a somewhat more self-conscious notion of the comic book as art.

Some of Mann’s funniest material is archival footage of anti-comic-book propaganda from the 50s, when Dr.

Read more

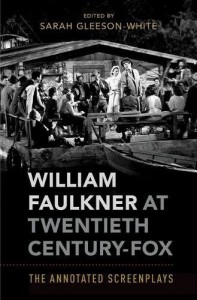

From Sight and Sound, July 2017. — J.R.

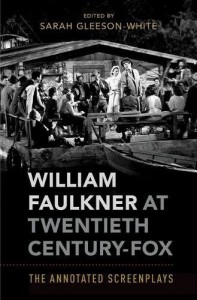

WILLIAM FAULKNER AT TWENTIETH CENTURY-FOX

The Annotated Screenplays

Edited by Sarah Gleeson-White, Oxford University Press, 949 pp., ISBN 9780190274184

Reviewed by Jonathan Rosenbaum

We know that Faulkner was no cinephile, but it’s less known that he referenced Eisenstein in The Wild Palms and cited Citizen Kane and The Magnificent Ambersons as two of his favourite films (along with High Noon) in a 1958 interview. One also can’t read the present-tense opening of Light in August without noting its cinematic immediacy, which suggests that consciously or not, Faulkner learned a lot from the movies.

Yet when it comes to his screenwriting, it’s closer to alienated, assembly -line labour than any significant form of self-expression. Editor Sarah Gleeson-White, a Sydney-based literary scholar, is well aware of this problem, beginning her Introduction with contradictory statements from Faulkner about how seriously he took this work (both of which, unsurprisingly, sound perfectly sincere) while noting that he wrote around fifty Hollywood screenplays between 1932 and 1954. That Faulkner was fully capable of working simultaneously on both his novel Absalom, Absalom and Hawks’ The Road to Glory is also duly noted. But Gleeson-White’s ambivalence about what actually constitutes screen authorship is reflected in the fact that several photographs in her commentaries are devoted to Faulkner’s Fox collaborators and none at all to Faulkner himself. Read more

From the Chicago Reader, October 29, 1995.

As the Chicago International Film Festival moves into its second week, two more films with distributors have been added to the list. Persuasion — a thoughtful, intelligent adaptation of the Jane Austen novel that provides a welcome alternative to Merchant-Ivory — is replacing Deathmaker and is being handled by Sony Pictures Classics. Things to Do in Denver When You’re Dead, filling the “surprise” film slot, is on all counts the dumbest Hollywood movie I saw in Cannes last May — an egregious Tarantino spin-off with everything the mainstream press is screaming for: a simple (even stupid) contrived plot, intimations of deranged and nonsensical violence, macho stances, movie stars, a fancy title, and the Miramax logo. It has nothing to do with reality and everything to do with someone pointing at Reservoir Dogs and saying, “Let’s have another one of those.” Under the circumstances, I guess the performances are OK.

Last week I suggested that the focus of this year’s retrospective, Lina Wertmuller — the recent recipient of the festival’s Golden Hugo for lifetime achievement — was a bizarre choice that might have been made interesting if the festival had issued a monograph explaining why her work was still worth defending or had some special relevance to the 90s. Read more

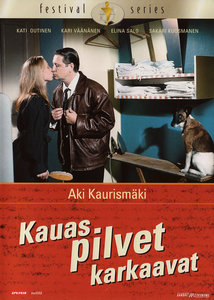

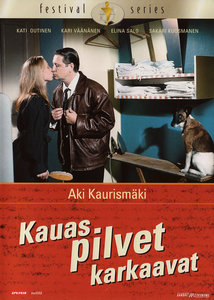

From the Chicago Reader (July 10, 1998). One thing that has recently led me to reconsider my estimation of Aki Kaurismaki is this superb, engaging appreciation of him by Girish Shambu.– J.R

Drifting Clouds

Rating ** Worth seeing

Directed and written by Aki Kaurismaki

With Kati Outinen, Kari Vaananen, Elina Salo, Sakari Kuosmanen, Markku Peltola, and Matti Onnismaa.

It might be risky to generalize about national character after visiting a country for only a week, but the particular kind of self-deprecating humor in all six features I’ve seen by Aki Kaurismaki was equally apparent during my recent visits to both Helsinki and the Midnight Sun film festival in Sodankyla. Kaurismaki and his older brother Mika, also a filmmaker, are the founders and guiding spirits of this festival, and its artistic director is one of their best friends, so the humor I’m describing is probably a type that flourishes under their eccentric auspices.

Roughly speaking, this attitude derives in part from the belief that Finns are perceived as the Poles of Scandinavia. Their language shares more roots with Hungarian and Estonian than with Swedish, Danish, or Norwegian, and Helsinki, by virtue of being only a few hours from Saint Petersburg, may have more links with Russia than with its Nordic cousins. Read more

From The Soho News (June 3, 1981). This is also reprinted in my first collection, Placing Movies: The Practice of Film Criticism. 2022: This remains for me De Oliveira’s greatest work, albeit his most neglected. As a treatise on how to adapt a great novel, it is surpassed only by Greed. J.R.

How can I persuade you that the best new movie I’ve seen this year, the only one conceivably tinged with greatness, is a voluptuous four-and-a-half-hour Portuguese costume melodrama, shot in 16-millimeter? Obviously I can’t. So rather than make you feel guilty about missing a masterpiece — as a couple of my friends managed to do when it was at MOMA last spring — let me assume at the outset that you will miss DOOMED LOVE all ten times that it shows at the Public between May 26 and June 14. Bearing this in mind, the following notes are an account of what you missed, are currently missing, or will miss.

1. If it’s confusing and misleading for some to call DOOMED LOVE an avant-garde film, this seems mainly because of the widespread working assumption that “avant-garde” is a social category above and beyond an aesthetic one. As industry-oriented critics like Kael and Sarris are frequently reminding us (the former obliquely, the latter unabashedly), the crucial professional issue is not what movies we go to as critics but what parties, junkets, festivals, universities, grants, and other circuits of power we have easy access to — not what we see but what we have is our calling card, whereas “taste” is largely a rationalization for the personal erotics of self-gratification, cooperation, conflict, and flattery founded on such a system of exchange. Read more

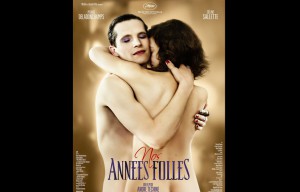

Written for the Chicago Reader (October 12, 2017). — J.R.

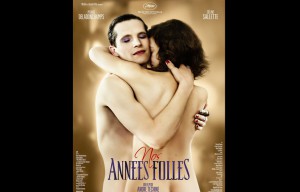

Golden Years

Nos Années Folles, the French title of this exquisitely upholstered and mysteriously provocative period drama, means “Our Crazy Years.” But as writer-director André Téchiné has suggested in such masterpieces as Wild Reeds and Thieves, being “crazy” simply means being human, alive, and horny. The protagonist (Pierre Deladonchamps), a passionately heterosexual soldier, disguises himself as a streetwalker to escape combat in World War I, then continues to wear drag in peacetime, yet his behavior seems no less rational (to him or to us) than that of little boys playing at war, or his adulterous wife (Céline Sallette) playing at marriage. For better and for worse, the mysteries remain unsolved and Téchiné’s elliptical tragic poetry prevails. —Jonathan Rosenbaum

Read more

Read more