Written in late July, 2014 for this recently published volume. — J.R.

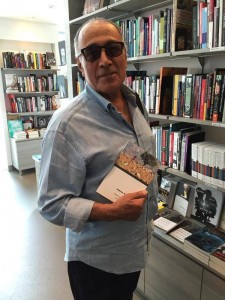

JONATHAN ROSENBAUM: Having by now covered practically all of the films of Abbas Kiarostami between us — starting with our book about him published in 2003, which dealt with all the films up through 10 (2002), and then continuing with further articles and dialogues since then, all the way up through Like Someone in Love (2012) -– it’s hard to know what we can add in the form of a Preface to the Persian translation of all of the above. Broadly speaking, I suppose one could say that over the past decade, Kiarostami has shifted from being an arthouse director to being a sort of gallery artist who worked in both film and still photography before finally, in more international and less Iranian terms, becoming an arthouse director again. Does this overall description of his evolution strike you as being accurate? And do you think Kiarostami has gained or lost anything in the process?

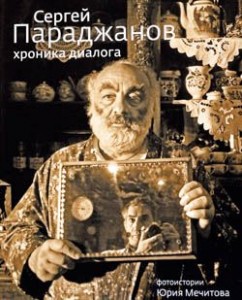

MEHRNAZ SAEED-VAFA: Your description sounds accurate to me, and I think Kiarostami has definitely gained something. He’s made several shorts and features going in different directions and styles that continue to challenge the expectations of his fans and followers. And obviously, his international audience has grown tremendously in the last decade and his films are now getting more attention from the mainstream critics who have to write about him — as a filmmaker and not just as an Iranian filmmaker. With his last two features made outside Iran, Certified Copy and Like Someone in Love, picking on more mainstream themes, he has maintained his arthouse quality in his cinema while becoming more commercially accessible. And he is truly interested in experimenting — writing scripts for other filmmakers, making shorts, and teaching his workshops are his other ways of constantly pushing the boundaries of cinema and filmmaking. One can argue that making art that attacks cinema as it exists is also a way of making cinema. I think about Paradjanov and all his years in prison, where he was making his collages and drawings — they were also forms of contemplation about cinema.