From The Soho News (September 3, 1980). –- J.R.

The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith

Written and directed by Fred Schepisi

Based on the novel by Thomas Keneally

For a good 80 percent or so of its running time, the experience

of seeing The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith affords a

salutary, beautiful shock. Films that are even halfway honest

about racism — Mandingo and Richard Pryor Live in

Concert are the most recent examples that spring to mind

— are so unexpected that they’re often accused of being racist

themselves, perhaps because of the deeply rooted taboos that

they expose and violate.

There’s no question that Fred Schepisi’s powerhouse Australian

movie — adapted from a novel by Thomas Keneally (who plays a

small but significant role as a lecherous cook), and “based on real

events that took place in Australia at the turn of the century”

(just before the federation of Australian colonies) – is agit-prop,

ideologically slanted. But then again, it’s hard to think of any

other current release — including, say, The Empire Strikes

Back and Dressed to Kill -– that isn’t.

The aforementioned hits perform in part the not-so-innocent

task of turning contemporary objects of confusion and disgust

(recent architecture and sex, respectively) into occasions for

exhilarated lyricism. The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith, no

less a feast for the eyes, intermittently succeeds in doing some

of the reverse. What all three films do in relation to the way we

live is equally political, whatever their apparent intentions.

Despite a soupy soundtrack score, which seems at times to

have been composed for a sluggish spectacle directed by J.

Lee Thompson, and a relish for beginning sequences with

startling close-ups that far exceeds any practical dramatic

utility that device can have, The Chant of Jimmie

Blacksmith is a stirring, often ingenious piece of invective

that deserves to be seen as widely as possible. It was made

two years ago, and, like a surprising number of other

interesting foreign films these days, has apparently circled the

globe at least eight times before arriving in up-to-date New York.

Meanwhile, it has been re-edited by writer-director Schepisi for

the more fidgety American market. (Perhaps significantly, he is

currently at work on a film in Hollywood.) From all the accounts

that I’ve been privy to, however, the original version — which also

had a somewhat elliptical narrative — dragged in spots. The

present one doesn’t, although there is an expositional bump or two,

and it appears that the deleted 14 minutes are relatively negligible.

***

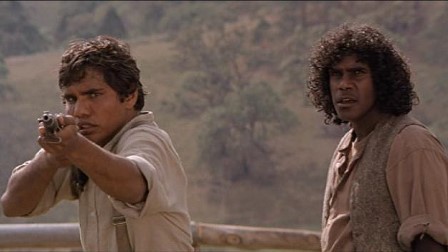

The title hero is a half-caste aborigine (forcefully played by Tommy

Lewis), reared and educated in a mission by Rev. Neville (Jack

Thompson) and his wife Martha (Julie Dawson) – charitable racists

who decide to help him out simply because he’s half-white. (As Martha

points out to Jimmie, his grandchildren will be only one-eighth black

if he can marry a white woman. )

The film’s percussive pre-credits sequence – concentrating on the

dynamic clash between Jimmie’a aborigine culture and Christianity

– economically establishes the schizophrenia that dominates the film

and its hero. When a friend whispered (apropos of Pauline Kael’s early

gloss), “It’s not The Birth of a Nation, it’s The Wild Child,” I knew

exactly what she meant.

Shot by Ian Baker in ravishing Panavision compositions that sometimes

evoke color photographs by Joel Meyerowitz (particularly those using

door frames), the early parts of the film chronicle Jimmie’s jobs in

picaresque fashion. These consist mainly of putting up fences for

farmers, sheep-shearing, working in a stable and tracking for the

odious Constable Farrell (Ray Barrett), the scummiest villain I’ve

encountered in any film all year. The latter job ultimately entails

informing on a black man who is then sexually abused and

murdered by Farrell, while Jimmie tries not to listen. The hero

is then ordered to bury his betrayed friend and assist in the

cover-up.

It’s around this point that Jimmie Blacksmith’s status and function in

the film become complex and interesting. Too complicitous by now in

the evils of the white world to qualify any longer as a simple, liberal

victim in Schepisi’s crafty dramaturgy, he nevertheless continues for

some time to be the only plausible identification figure. When, after

suffering a great deal more intolerance and provocation much later

in the film (I’ve skipped a lot of the plot), he proceeds to commit mass

murder with the help of his Uncle Tabidgi (Steve Dodds), he becomes

a figure of extraordinarily ambiguous epic proportions — a Nat Turner

seen in Brechtian terms.

The only problem is, having performed this remarkable act of moral

violence on the spectator, Schepisi seems to have been at a loss about

what to do next. As soon as Jimmie becomes a fugitive outlaw (“I’ve

declared war, that’s what I’ve done”), his half-brother Mort (a purer

aborigine appalled by Jimmie’s continuing violence, played by the

very expressive Freddy Reynolds) becomes the central identification

figure — a sort of pagan, pre-intellectual Pierrot le fou.

Then McCready (Peter Carroll), an asthmatic white schoolteacher

taken along as hostage by Jimmie and Mort, emerges briefly as the

film’s moral spokesman, especially when he addresses Jimmie about

Mort: “He’s not really your brother, he’s an aborigine. There’s still

too much Christian in you. It’ll bugger him up, the way it’s

buggered you.”

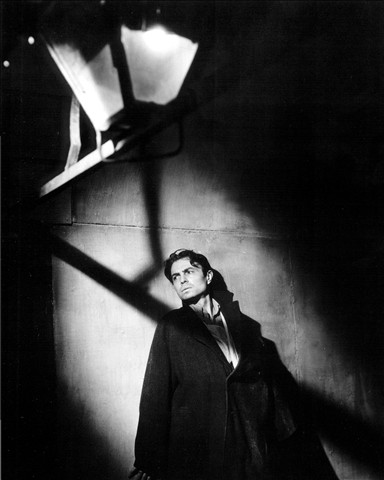

But by this time, the narrative focus has become too diffuse. When

the film finally resumes its concentration on the title hero, he has

turned into an allegorical and mythical Christ figure, wounded and

unconvincing — rather like James Mason at the end of Odd Man Out.

The lapse is unfortunate, but far from lethal. The Chant

of Jimmie Blacksmith still contains enough energy and

insight and talent to warrant a look from anyone, whatever

its flaws. If Schepisi’s next film achieves even a fraction

of what this one sets out to do, it’ll clearly be something to watch.