From The Soho News (September 3, 1980). –- J.R.

The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith

Written and directed by Fred Schepisi

Based on the novel by Thomas Keneally

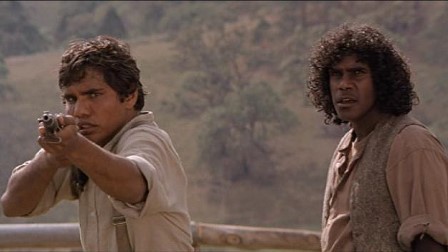

For a good 80 percent or so of its running time, the experience

of seeing The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith affords a

salutary, beautiful shock. Films that are even halfway honest

about racism — Mandingo and Richard Pryor Live in

Concert are the most recent examples that spring to mind

— are so unexpected that they’re often accused of being racist

themselves, perhaps because of the deeply rooted taboos that

they expose and violate.

There’s no question that Fred Schepisi’s powerhouse Australian

movie — adapted from a novel by Thomas Keneally (who plays a

small but significant role as a lecherous cook), and “based on real

events that took place in Australia at the turn of the century”

(just before the federation of Australian colonies) – is agit-prop,

ideologically slanted. But then again, it’s hard to think of any

other current release — including, say, The Empire Strikes

Back and Dressed to Kill -– that isn’t.

The aforementioned hits perform in part the not-so-innocent

task of turning contemporary objects of confusion and disgust

(recent architecture and sex, respectively) into occasions for

exhilarated lyricism. Read more

This article and interview was originally published in the May-June 1973 issue of Film Comment, roughly half a year after the interview took place. I went to work for Tati as a script consultant several weeks after I had the interview, but well before it appeared in print. A few years ago, this piece was reprinted online in the Southern arts magazine Drain. —J.R.

Tati’s Democracy

An Interview and Introduction

Jonathan Rosenbaum

Like all of the very great comics, before making us laugh, Tati creates a universe. A world arranges itself around his character, crystallizes like a supersaturated solution around a grain of salt. Certainly the character created by Tati is funny, but almost accessorily, and in any case always relative to the universe. He can be personally absent from the most comical gags, for M. Hulot is only the metaphysical incarnation of a disorder that is perpetuated long after his passing.

It is regrettable that André Bazin’s seminal essay on Jacques Tati (“M. Hulot et le temps,” 1953, in Qu’est-ce que Ie cinéma? Read more

Written for Criterion’s DVD release of F for Fake in 2005. — J.R.

There were plenty of advantages to living in Paris in the early 1970s, especially if one was a movie buff with time on one’s hands. The Parisian film world is relatively small, and simply being on the fringes of it afforded some exciting opportunities, even for a writer like myself who’d barely published. Leaving the Cinémathèque at the Palais de Chaillot one night, I was invited to be an extra in a Robert Bresson film that was being shot a few blocks away. And in early July 1972, while writing for Film Comment about Orson Welles’s first Hollywood project, Heart of Darkness, I learned Welles was in town and sent a letter to him at Antégor, the editing studio where he was working, asking a few simple questions—only to find myself getting a call from one of his assistants two days later: “Mr. Welles was wondering if you could have lunch with him today.”

I met him at La Méditerranée — the same seafood restaurant that would figure prominently in the film he was editing — and when I began by expressing my amazement that he’d invited me, he cordially explained that this was because he didn’t have time to answer my letter. Read more