I’ve lost track of when I originally posted this, but it may have been on March 21, 2012. In any case, the English version of this collection is now available. — J.R.

This book has clearly been a long time coming. Like Pedro Costa and (the otherwise very different) Alain Resnais, Jean-Marie Straub and the late Danièle Huillet should be regarded as film critics and film historians who aren’t really writers in any ordinary sense. (Resnais’ critical and historical gifts, I would argue, are mainly apparent in his films rather than in his interviews.) When I curated the last American retrospective of Straub-Huillet’s work to date almost thirty years ago, the accompanying catalogue of essays that I put together to accompany this event, partially with their advice and assistance, included a lengthy section entitled “Straub and Huillet on Filmmakers They Like and Related Matters,” drawn from a dozen separate sources and translated, when necessary, by me — not always gracefully, I’m sorry to say. (I’ll be posting my lengthy Introduction to this catalogue a couple of days from now.)

Although it’s beyond my current means to reproduce the entirety of “Straub and Huillet on Filmmakers They Like and Related Matters” here (I wish I could), I can offer a sampling from it below, some of which appears in their original French in Écrits (e.g., the texts on Lubitsch and Dreyer), and some of which is drawn from interviews and public appearances in English (e.g., the texts on Tati, Renoir, Buñuel, Hawks, and Nicholas Ray), which don’t appear there. Like Straub’s revelatory comments about Chaplin in Pedro Costa’s Where Lies Your Hidden Smile? and Costa’s own remarks about Bresson, Chaplin, Griffith, Lubitsch, Mizoguchi, Ozu, and Tourneur (among others) in his lecture “A Closed Door That Leaves Us Guessing,” the texts and comments found below are, I believe, superb examples of film criticism and film history (at least when they aren’t simple journalism, as in Straub’s transcriptions of some of Dreyer’s remarks.)

Écrits is divided into three sections —“Textes,” “Portfolio” (photographs taken and annotated by cinematographer Renato Berta), and “Atelier” (various work documents, including several letters written by Huillet to Berta or to cinematographer Willy Lubtchansky, with annotations by Straub) — and some of the early texts are basically journalism, more valuable as historical background to Straub-Huillet’s work than as either criticism or as history per se. (As the earliest pieces here, from the mid-1950s, show, Straub basically started out, like the slightly younger Luc Moullet, as a dutiful disciple of Cahiers du Cinéma‘s Young Turks, that is to say, a “Hitchcocko-Hawksian” — praising Rear Window at the 15th edition of the Venice film festival (while expressing skepticism about The Seven Samurai) and showing comparable piety towards middle-period Rossellini and Nicholas Ray’s Johnny Guitar during the same period; his subsequent misgivings about Ray, which are touched on below, started somewhat later.) The most conspicuous omission in the collection is a very lengthy study of Antonioni’s first feature, written in the 50s and running to about 70 manuscript pages, which André Bazin told Straub was too long for a magazine article and too short for a book. In their brief Préface to Écrits, editors Philippe Lafosse and Cyril Neyrat report that Straub burned this monograph shortly after he served as an assistant on Rivette’s Le coup de berger and shortly before he left France for Germany (to avoid serving in the French army, which at that time meant being sent to Algeria).

When he and Huillet came to New York for their retrospective in 1982, I recall how startled I was when I discovered that, in spite of his love of other late Ford films, he had nothing but scorn for The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance. When I asked him about this again years later, at the Viennale, during a joint retrospective devoted to Straub-Huillet and Ford, he made it clear that he no longer held this position, but here in Écrits is evidence of his original verdict on the film, when he notes in his responses to a 1966 questionnaire that “Ford, after having led American cinema to its apogee (Two Rode Together, The Searchers, and The Horse Soldiers) and having precipitated its downfall (Liberty Valance, Cheyenne Autumn),” returned to sublimity with Seven Woman.

***

On Ernest Lubitsch (by Jean-Marie Straub, sent as a letter to Cahiers du Cinéma):

His films have become as important for me as those by Lang and Murnau. Die Augen der Mumie Ma is already Eschnapur, and Carmen,The Golden Coach. Der Stolz der Firma, so funny and, finally, so Brechtian; the same goes for Madame Dubarry, which demonstrates in three shots a policier provocation, and Lady Windermere’s Fan, more beautiful and more dense than the most marvelous Hitchcocks.

***

On Carl Dreyer: Ferocious (by Jean-Marie Straub)

What I particularly admire in the Dreyer films that l’ve been able to see or see again over the past few years is their ferocity in respect to the bourgeois world: its notion of justice (The President, which is one of the most astonishing narrative constructions that I’ve known, and one of the most Griffith-like films, hence one of the most beautiful), its vanity (the feelings and décors of Michal), its intolerance (Day of Wrath, stupefying through its violence, and through its dialectic), its angelic hypocrisy (“She’s dead . . . she’s no longer here . . . she’s in heaven,” says the father in Ordet, and the son replies: “Yes, but I loved her body, too…”), and its puritanism (Gertrud, so well-received for that by the Parisians on the Champs-Elysées).

In other respects, Vampyr (“There are no children here and no dogs”) remains, remains, ever since the day I saw it thirteen years ago on rue d’Ulm, for me the most resonant of all films. And in 1933, Dreyer was sending out that call that, apart from Amico and Bertolucci, the present-day Italian filmmakers would do well to finally understand:

If one is striving to create a realistic space, the same thing must be done with sound. While I am writing these lines, I can hear church bells ring in the distance; now I perceive the buzzing of the elevator, the distant, very-far-away clang of a streetcar, the clock of city hall, a door slamming. All these sounds would exist, too, if the walls in my room, instead of seeing a man working, were witnessing a moving, dramatic scene as background to which these sounds might even take on symbolic value — is it right then to leave them out?…In the real sound film, the real diction, corresponding to the unpainted face in an actually lived-in room, means common everyday speech as it is spoken by ordinary people.

And at the present, when so many young authors dream only of imposing their ideas and their petty reflections in their films, seducing or raping (patronizing Brechtianism,or the utilization of advertising techniques and the propaganda of capitalist society) or even disappearing (collages, etc.), let us listen to Dreyer:

The Danish author, Johannes V. Jensen, describes “art” as “soulfully composed form”. That is a definition which is simple and very much to the point. The same goes for the definition the English philosopher Chesterfield gives to the concept of “style”. He says “style is the dress of thoughts”. That is right, provided that “the dress” is not too conspicuous, for a characteristic of good style must be that it enters into such an intimate bond with matter that it is absorbed into a higher unity with it. If it imposes and strikes the eye, it is no longer “style” but “mannerism”.

Style in an artistic film is the product of many different components, such as the play of rhythm and composition, the mutual tension of color surfaces, the interaction of light and shadow, the measured gliding of the camera. All these things, in association with the conception that a director has of his material, determines his style. . .

I don’t underestimate the teamwork performed by cinematographers, color technicians, set decorators, etc., but within this collectivity, the director must remain the driving force, the man behind the work who makes the writer’s words resound and the feelings and passions spring forth, so that we are moved and touched….So this is my understanding of a director’s importance — and his responsibility.…To show that there is a world outside the dullness and boredom of naturalism, the world of the imagination. Of course, this conversion must take place without the director and his collaborators losing their grasp of the world of reality. His remodeled reality must always remain something that the public can recognize and believe in. It is important that the first steps towards abstraction be taken with tact and discretion. One should not shock people, but guide them gently onto new paths.

Each subject implies a certain voice (route).* And that must be heeded. It is necessary to find the possibility for expressing as many voices (routes) as one can. Itis very dangerous to limit oneself to a certain form, to a certain style….That is something I really tried to do: to find a style that has value for only a single film, for this milieu, this action, this character, this subject.

ln the cinema, you cannot play the role of a Jew, you have to be one.

The fact that Dreyer was never able to produce a film in color (he had thought about it for more than twentv years) nor his film on Christ (a profound revolt against the state and the origins of anti-Semitism) reminds us that we live in a society that is not worth a frog’s fart.

*Straub’s quotations from Dreyer are drawn from four sources: “The Real Talking Film” (1933),“Imagination and Color” (1955), a 1965 interview with Michel Delahaye and an unknown text, respectively. The versions of the first two here are adapted from Donald Skoller’s Dreyer in Double Reflection (New York: E.P. Dutton, 1973); the third is adapted from the English translation of the Delahaye interview in Andrew Sarris’s Interviews with Film Directors (New York: Avon, 1967). In the original French version (in Cahiers du Cinéma No. 170, Septembre 1965), it isn’t clear whether Dreyer is saying “voix” (voice) or “voie” (route).(Trans.)

***

On Jacques Tati and Jean Renoir

STRAUB: …The films of Tati are successions of difficulties.

HUILLET: Precisely, the most difficult thing to recapture in cinema is what one sees continually in the street: awkward gestures, gestures which are interrupted.

STRAUB: The most beautiful shot of Renoir’s Picnic on the Grass is when Paul Meurisse is in the kitchen, when he has rediscovered Nenette; she leaves, she goes out to look for some thread, and when she has left, Renoir lingers on Meurisse. It is obvious that Meurisse (this wasn’t anticipated in the shot) at this moment is facing death, one feels it very strongly. He looks forty years older than his age. It’s the moment when he reaches his decision to marry the girl. That is, to throw everything overboard and revolt…that is felt. Any producer would have cut that. Renoir in fact kept it.

***

On Jacques Tati

STRAUB: . . . I like very much like the last Tati [Parade]. Rivette was absolutely right when he said that Tati has become a political filmmaker. What he does with the blown-up video material, what he gets from it, is extraordinary. And it’s outside that political group, those people who come out of the cinema in the evenings and experience reality entirely differently. What is exciting in Parade is that it is a film about all the degrees of nervous flux, beginning with the child which cannot yet make a gesture, which can’t co-ordinate its hand and its brain, and goes up to the most accomplished acrobats.

***

On Luis Buñuel and Nicholas Ray

PHIL MARIANI: In Machorka-Muff, the opening night sequence, the dream, the circumstantial discovery of the letter, all have a Surrealistic quality.

STRAUB: That was conscious.

MARIANI: Surrealism doesn’t seem relevant in the general context of your films, but was it an early influence?

HUILLET: Even in Chronicle [of Anna Magdalena Bach].

STRAUB: In Machorka-Muff it was conscious because at that time, I was a little bit more interested in the paintings of Salvador Dali. The film has nothing to do with his paintings. I was not trying to say, like some filmmakers, that I was inspired by Salvador Dali –- no, you are making a film. Bresson said, “I used to be a painter, that is exactly the reason why I am making a film, I avoid painting.” But in Machorka-Muff it was conscious.Even the scene of laying the cornerstone, that was completely Surrealistic…

MARIANI: How about Buñuel? Had you seen his films by that point?

STRAUB: Oh, yes, that must have been an influence. I saw a lot of times many “B” pictures that he made in Mexico . . . and I knew very well Las Hurdes, L’age d’or, Un chien andalou.

HUILLET: There is a French film by Buñuel called Fever Mounts in El Pao from which [Straub] always said he would not have ever made Othon if he had not seen this film.

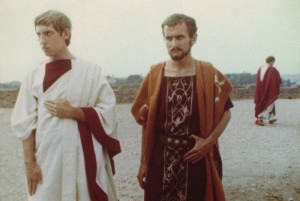

STRAUB: The films are completely different, I hope. But that’s a story about a dictatorship in a small South American country.

HUILLET: The two films I saw, after which I decided I would try to make documentaries, were Los Olvidados and another one by Mizoguchi.

MARIANI: Buñuel would be another person for that category of uncompromising resister?

STRAUB: I did not say uncompromising but, yes, able to resist.

HUILLET: Buñuel was and has become a real good bourgeois and that was very interesting because in Los Olvidados he is not compromising with violence, and he is not fascinated by it, but he is very clear and unsentimental about it, like Hawks in Scarface.

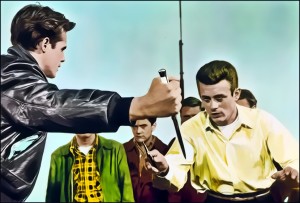

STRAUB: The exact contrary to Buñuel is Nicholas Ray, even when I am interested in his films (but not like Mr. Wenders or a lot of French people). He is always fascinated by violence —

HUILLET: — afraid and fascinated –

STRAUB: — and so, at a certain moment, he slips on the side of the police.

HUILLET: Which Buñuel never does