2021 note: In part because I had unkind things to say about his first feature in 1974, writing at the time from Paris, my relations with Bertrand Tavernier (1941-2021) tended to be strained, even though both of us periodically tried to overcome this rift — and, to his credit, he was the one who made the first friendly gesture, inviting me to join him for a meal in Chicago many years later.. Round Midnight is probably the film of his that has affected me the most, which is why I’m reposting this piece now.

Part of my 1987 application for the job of film reviewer at the Chicago Reader consisted of writing three long sample reviews for them in March and/or April — only one of which was published by them (Radio Days), although, as I recall, they paid me for all three. (Writing these pieces in Santa Barbara, I was limited in my choices of what I could write about.) I only recently came across the two unpublished reviews, of Platoon and Round Midnight, in manuscript, although I recall that I did appropriate certain portions of them in subsequent reviews. Otherwise, the first publications of these pieces are on this site. — J.R.

***ROUND MIDNIGHT

Written by Bertrand Tavernier and David Rayfiel

Directed by Tavernier

With Dexter Gordon, François Cluzet, Sandra Reaves-Phillips, Herbie Hancock, Bobby Hutcherson, and Martin Scorsese.

I just can’t take that bullshit, you dig? They want everybody who’s a Negro to be an Uncle Tom, or Uncle Remus, or Uncle Sam, and I can’t make it. It’s the same all over, you fight for your life — until death do you part, and then you got it made. — Lester Young in Paris, 1959

There are plenty of cases to make against Round Midnight: sentimentality, chauvinism, an unmistakable vagueness and softness of conception around the edges. But it would be a pity to let these shortcomings allow one to overlook the fact that someone has finally made a fiction feature about jazz with love and respect for and some modicum of understanding about its subject. That it has taken the sound cinema well over half a century to accomplish this is less a mystery than a scandal. That the one to accomplish this should be a petit-maître of French middle-class cinema might in some ways be an even harder pill to swallow. But accomplish it Tavernier has, and before all else, this modest if unprecedented achievement deserves to be acknowledged and applauded.

Considering the nearly parallel developments of film and jazz as the new art forms of this century, it is disheartening to consider how seldom they’ve been able to work together interactively without some fatal compromise on either side (which usually means one serving as ballast for the other). The documentaries have been hampered by a nervous reluctance to let the music speak for itself, characteristically interrupting numbers with distracting cutaways and voiceovers (which often perversely tell us how great the music we’re no longer hearing is supposed to be), while the fiction films have been undone both by ignorance about the music and by an uncertainty about how to integrate it into a dramatic context. For examples of the latter, one could cite otherwise sympathetic fiction films like Too Late Blues and New York, New York as well as otherwise unsympathetic ones like Paris Blues and The Cotton Club; from this standpoint, Martin Scorsese’s effective cameo in Round Midnight can be interpreted as a form of penance for his indifference to jazz history in New York, New York.

Significantly, all these problems were admirably faced and solved by a single filmmaker in 1929, the first year of talkies. In two low-budget shorts made respectively with Bessie Smith and Duke Ellington, St. Louis Blues and Black and Tan, Dudley Murphy, who previously had worked with Fernand Léger on the experimental masterpiece Ballet mécanique, and later directed Paul Robeson in The Emperor Jones — set precedents that in some respects no subsequent jazz films have lived up to, Round Midnight included. Admittedly both films are fictional, and I am being a bit rhetorical when I state that St. Louis Blues is valuable chiefly as a documentary record of our greatest blues singer, while Black and Tan, with its audacious poetic linkage of death and orgasm with the structure and emotion of Ellington’s music, stands as the great example of utilizing jazz within a narrative. The point is that in these two short and mainly unheralded films, despite some dated racial stereotyping and primitive methods of sound recording, Murphy set down certain fruitful possibilities for jazz and film that have seldom been considered since. Indeed, looking through the thousands of entries in David Meeker’s Jazz in the Movies, one is confronted mainly by ephemera, embarrassments and gaping lacunae. To cite only one sobering example, if we look for any sound film record of Charlie Parker, the greatest of all jazz musicians, we can only find one brief and not very satisfying number from a 1951 TV broadcast. [2011 postscript: this was before my discovery of Gion Mili’s wonderful if silent footage for his unfinished Improvisation, which I wrote about briefly here.]

Acutely aware of this neglect, Round Midnight sets out to rectify the balance in as many ways as it can. Some of the results of this scrupulous integrity may be apparent only to jazz aficionados, but they are there all the same, and virtually for the first time. Nearly all of the music is recorded live, and we’re usually allowed to listen to it without impediments, as an extension of the characters and narrative rather than as some discontinuous interlude leading away from them. If Tavernier cuts away from the bandstand for a flashback or flash-forward over the continuing music, this usually serves only to increase the dramatic impact of coming back later — accepting and even exploiting the mental drift that often accompanies listening to music without ever using this as a pretext for letting us forget that the music is there. Futhermore, the lengthy takes and contemplative camera movements allow one to linger over the music and crawl into its textures: there is none of the pile-driving or force-feeding that one comes to expect from rock videos.

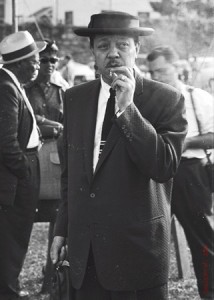

The musicians hired are among the best now playing, and if the film never goads them into the brilliance that they’ve shown on other occasions, the overall level of performance is still fairly high. (Regrettably, the most exciting number in the film — Sandra Reaves-Phillips’ exuberant version of a Bessie Smith blues at a party jam session — is missing from the soundtrack album.) The most conspicuous case of a musician playing below his best is also probably the most justifiable in terms of plot: Dexter Gordon, who suffered from health problems during the shooting, plays a character who is so clearly past his peak that references to his former brilliance partially have to be accepted on faith. Fortunately, Gordon’s extraordinary qualities as an actor make this faith pretty easy to come by. Insofar as the script is virtually sculpted around his particular place in jazz history, the part of Dale Turner is tailor-made for him — even though it must be emphasized that it is a real part and not a transparent cover for Gordon himself.

As a crucial figure linking swing and bebop who spent many years as an expatriate himself (mainly in Copenhagen), Gordon conveys a cool demeanor within a hard bop context, and ranges across the spectrum of jazz like few of his contemporaries. Given this spread, there is a certain logic in basing his character on both Lester Young and Bud Powell (with embellishments from his own career as well as Ben Webster’s), even though this produces a rather blurry collage at times. From Young comes Dale Turner’s personalized slang, drinking problem, a singer (Lonette McKee) meant to remind us of Billie Holiday, and a recounted traumatic experience in the army. From Powell comes the long Paris exile, the French jazz buff named Francis who takes care of his idol, and the black woman who takes care of him before Francis comes along (named Buttercup, after Powell’s wife). Mainly omitted from Turner’s background, except by the barest suggestion, is the long history of Powell’s mental illness and electroshock treatments — as well as the frenetic, driven quality of Powell’s playing.

A key musician for Jack Kerouac and some of the other Beat writers, Gordon all but minted certain hipster gestures and stances — such as holding up his tenor sax horizontally after a number to greet applause, and reciting the lyrics to certain ballads before performing them — many decades ago, and it is not surprising to hear that he has acted before. His earliest film performances are with Louis Armstrong’s band in Atlantic City and Pillow to Post, two minor musicals of the mid-40s. While doing time in Chino (a California prison without bars) on a narcotics charge in the mid-50s, he did his first real acting in Unchained, a low-budget feature shot there (his best line: “They can’t write it the way we play it, man; just forget the music and follow us”). In 1960 he acted on stage in the Los Angeles production of The Connection; since then he has done the same play in Denmark and a couple of bit parts in Swedish films.

Towering at a gangling 6’5″ over his French admirers, Gordon has an otherworldly comic air evocative of Tati’s Monsieur Hulot, and his singular acting style demands to be read and appreciated in jazz terms. Like most of the patron saints of this movie — Count Basie, Miles Davis, Thelonious Monk and Lester Young — Gordon builds his best dramatic effects on ellipsis and shorthand, knowing just when to lay out or hold back with a pregnant pause, playing a teasing guessing-game with his audience about when he’ll come up with his next phrase. A master of witty delivery, Gordon has an uncanny knack for taking humdrum lines — “you know, it just occurs to me that bebop was invented by the cats who did get out of the army” — and turning them into profundities with his gravel-heavy voice. Part of this is a consequence of who Gordon is as well as what he says; insofar as Round Midnight contrives to combine some measure of documentary with its very romantic fiction, he figures as a witness as much as a participant, and from this standpoint, few living musicians are better qualified. (Significantly, he and the other musicians in the cast collaborated on their own dialogue.) Looking like a monument in ruins, Gordon can charge the movie with unusual power through his presence alone.

And what has all this, one might ask, to do with Bertrand Tavernier? As a director whose well-crafted, middle-class/middle-brow forays have often suggested a passionate defense of mediocrity — his Oscar-winning Sunday in the Country comprising in this respect a veritable Oatmeal Manifesto — he has not so much abandoned his customary muse here as obliged some of us to reconsider it. Dale Turner is presented to us throughout from the vantage point of Francis Borier (François Cluzet), an adoring French fan with cocker spaniel eyes who is as mediocre a personality as one could hope to find in any Tavernier film. Like the characters most often played by Philippe Noiret in other Tavernier features, he functions partially as the director’s surrogate and partially as his model of exemplary mediocrity. Based on the real-life Francis Paudras, who cared for Bud Powell during his years in Paris, this divorced commercial artist with a young, neglected daughter is presented to us without a shred of irony. (“You know, you changed my life,” he says to Turner at one point. “Without you, I never would have read Rimbaud.”) Yet as drippy as he is, he serves as an ideal narrative device for honestly conveying Tavernier’s own distance from his subject. All proportions guarded, his role resembles that of the narrators Lockwood and Nelly Dean in Wuthering Heights — the square, humane witness of a Heathcliffian legend who can offer us only a partial portrait, compelling us to imagine the rest.

Before he was a film director, Tavernier worked as a film critic specializing in American cinema, and Round Midnight, set in the Paris of 1959, can be regarded as an elegy to the widescreen Hollywood movies of his youth, and a tribute to the jazz of that period as well. The plaintive wail of Miles Davis is often recalled (most often when Gordon switches to soprano sax), and no less nostalgic a spell is conjured up by Alexandre Trauner’s beautiful period sets — loving recreations of Paris’s Blue Note and New York’s Birdland (both made to glow like pirates’ lairs), and a couple of Paris exteriors — the outside of the Blue Note and a Left Bank Hotel habituated by black musicians — which blend the real with the dreamlike in a poetic manner recalling Trauner’s 19th century Paris in Children of Paradise. It is easy to forgive some of the cornball pretexts from a director so bent on recapturing the visceral pleasures of jazz and movies alike: reconstructing an old-fashioned montage sequence out of something like The Hustler (1961); cutting in mid-flight from a posthumous big-band rendition of Turner’s ode to his lost daughter to Turner’s first performance of the same melody in Birdland some years earlier.

What rankles about Tavernier’s customary embrace of a realist aesthetic is its flattery of middle-class taste, confirming what an audience already thinks it knows. Without actively denying this aesthetic (apart from Trauner’s nonrealistic exteriors), Round Midnight complicates it by maintaining such a shy and reverential distance from Turner — a character about whom we know surprisingly little, for all his impact and resonance — that we’re allowed some complacency only about what we feel; what we know remains altogether less certain.

French idolatry for some kinds of art clearly has its excesses, and one wishes that Tavernier had a bit more sense of the potential foolishness of the humorless Francis, gazing endlessly at silent home movies of his blitzed-out hero. At the same time, putting these and related excesses alongside the puritanical refusals of our usual Anglo-American indifference, it theoretically becomes possible to prefer them, at least as a guide to seeing how we could savor our lives a bit more than we do. Round Midnight implies at the very least that France has offered a warmer haven to some black American musicians than their own country has. Obviously this idea isn’t restricted to the French — the bitter poetry of Lester Young’s statement in an interview at the head of this review suggests a similar notion — and Tavernier’s plot is sufficiently close to what actually happened to Bud Powell when he returned to the states to give this sentiment some added weight. Yet even if we accept this as self-righteous chauvinism, Round Midnight justifies its own claims simply by existing. (If an American director had made a fiction feature about jazz as serious, we might have cause for complaint. Made as a French-American co-production, the film apparently owes the participation of Warners to producer Irwin Winkler, as well as Clint Eastwood’s enthusiasm for the project as a jazz buff.)

Getting back to a lesson provided by Dudley Murphy’s early jazz shorts, the greatest affinity between film and jazz as art forms may be the degree to which they remain collective enterprises and experiences, depending on accommodation, coordination and shared feelings: Bessie Smith singing out her sorrow in a crowded bar, Duke Ellington performing his “fantasy” with his band huddled around the death bed of a cherished friend. From this standpoint, it may be misleading to regard Round Midnight as an auteurist film in relation to either Tavernier or Gordon. Better to see it as a complex three-way transaction between them and us, with lots of others helping. Within such exchanges, Francis’s love for Dale and Tavernier’s love for the music become two parts of the same process which we’re invited to share — for better and for worse.