From American Film (December 1979). I’ve trimmed this a bit. — J.R.

“Production alternatives, linguistic and symbolic mutations, new models of the entertainment spectacle, new forms of film consumption, the relation between various media, the financial state of various film industries…”

In the words of an introductory brochure, these were some of the topics and problems to be explored at an international conference, “Cinema in the 80s,” set in the midst of the Venice Biennale. For the thirty-odd speakers, myself included, who had been flown all the way to the Palazzo del Cinema on the Lido, there was plenty to think about while overcoming jet lag.

The conference’s three days were devoted to language, industry, and audience, in that order. Simultaneous translation (of a sort) over earphones offered versions of each speech in Italian, French, English, German, and Spanish. Despite these noble efforts, the conference inevitably evoked a Tower of Babel at times. Bringing together academics, critics, and filmmakers from half a dozen countries, thre sessions helped to clarify how far most members of each profession are today from speaking a common tongue. Specialists and experts on their elected turfs, they often respond like fish out of water when confronted with film people of different sorts. Seldom, indeed, have the separate approaches and terminologies of the university, the press, and the film industry seemed so achingly distinct.

The first session had a heady unpredictability in which such strange bedfellows as Shirley Clarke, Joseph Losey, and Jean Rouch, critics Jean Douchet, Raymond Durgnat, and Andrew Sarris, and theorists Raymond Bellour, Gianfranco Bettini, and Jacqueline Rose all tried to share the same podium.

Some of the resulting juxtapositions were striking, to say the least. One could pass directly from a wry observation of Bettini – that we live today between two possibilities, the terrible and the trivial – to enthusiastic, utopian projections from Rouch regarding technological changes in film.

Rouch reported that some of these changes have enhanced a feedback technique he uses whereby Africans can criticize his own filmed images of them. This is a technique that has remained central to Rouch’s anthropological research for well over twenty years. One even feels it in the background of his latest film, shown at the Biennale during the conference –- Funeral in Bongo: Old Anai, 1849-1971, a hypnotic account of a ceremony in the Bandiagara region, as lyrically mesmerizing as a John Coltrane record.

Is it possible that the optimism of Rouch’s approach merely reflects the positive thinking of the filmmaker, as opposed to the less confident future conjured up by the theorist? The differences between theory and practice remained pronounced, in any case, throughout the conference.

Between the theorists and filmmakers were the critics, many of whom seemed equally stranded and isolated. The prolific English critic Raymond Durgnat, for instance, offered some stinging remarks about the conference’s organization –- protesting that he’d been asked to participate in a discussion about authorship that had never materialized. Piqued even more by the tone of exclusivity and elitism that he detected in much of contemporary French theory, he launched an attack on Jacques Lacan and Louis Althusser, the latter of whom he nicknamed “Ayatollah”. They were described, respectively, as “a primitive Freudian revivalist” and “a Stalinist”.

While Durgnat’s passion offered a welcome contrast to some of the drier academic complacencies, the possibilities of any fruitful exchange were lost when Durgnat walked out of the conference in midstream, leaving most responses to his talk to fend awkwardly for themselves. And to complicate the proceedings further, surprise guests like Peter Bogdanovich -– who had just shown Saint Jack at the festival -– were suddenly brought to the podium without warning to answer press-conference-type questions from the audience. (Ironically, the discussion of authorship that Durgnat had been promised materialized only after his departure and, inadvertently, in some of Bogdanovich’s off hand remarks, which were mainly about himself.)

***

Due to the equivalent of battle fatigue, I missed the conference’s Sunday morning sessio, devoted to industry, for some much-needed R and R at the Piazza San Marco in Venice. But I returned in time to sample an Italian television documentary made for RAI about the decreasing availability of serious European films in the United States. This has been a deepening problem over the past decade that is seldom discussed in American film journals. It has even been exacerbated by many of the leading U.S. film festivals, which increasingly tend to rubber-stamp the more commercial imports rather than display more experimental and ambitious fare.

It was interesting to discover, though, that this well-balanced inquiry into the subject mainly depended on knowledgeable comments from Americans — including such commentators as Dan Talbot of New Yorker Films, Martin Scorsese, and the Museum of Modern Art’s Adrienne Mancia. Susan Sontag, who also appeared, rightly complained that the work being done by distributors today is very poor, and she reflected sadly on the number of art theaters in Manhattan that have been turned into porn houses.

The conference had already called attention to important and undistributed European work the previous day, when it screened an episode from Jean-Luc Godard’s French television series, 6 X 2 — just one fragment of an ambitious, extended oeuvre in film and videotape that has been consistently ignored in America over the past seven years. Even without translation, Godard’s intricate reflections on life, work, and art remain startling and provocative. His recent method of writing with an invisible hand and pen over his video images — a witty game involving circles, arrows, and words — evokes an animated cartoon by Saul Steinberg, or a philosopher’s dream.

And why have Godard’s latest works become so scarce? Warners marketing executive Lee Beaupré obliquely suggested one explanation when he remarked that young people in the United States today are as insular as their parents were in the fifties, and that aspiring filmmakers currently prefer to see themselves more as would-be entrepreneurs than as would-be artists (the sixties model).

Beaupré’s principal prediction about the eighties was that even fewer theatrical features would be made than in the seventies. Most of these, he said, would fit one of three categories: big-budget films with stars, films in which the size of the image is crucial, and films such as Rocky which depend largely upon communal audience responses. Beaupré further forecast that the most popular European films in the United States would continue to be those that offered limited naughtiness and mild titillation, rather than serious challenges to established institutions (the New Wave model).

Beaupré’s comments, following a detailed presentation from Larry Finley of the International Tape Association about new and upcoming video products — an illustrated slide talk that seemed indistinguishable from advertising — offered a much more refined version of the same implied prognosis: more equipment and fewer films. It is arguably a point that could be extended to take in an overall decrease of content in media itself. As Beaupré put it, media is as responsible for hyping and overexposing certain big films as any studio.

***

The final day of the conference, devoted to audience, began with an introductory paper from French sociologist Pierre Sorlin. Arguing that our society is fundamentally based on inequality, and that it uses media as a form of “equalization,” Sorlin compared the “absolute” racial segregation of movie audiences in Cleveland with the “relative” segregation of those in Buffalo, a city with nearly the same size population. For later comparisons, he also discussed a town in southern Turkey, arguing persuasively that the way a film is “read” or interpreted has a close relation to where it’s shown, and in what social situation.

A perfect illustration of Sorlin’s latter point could be found by comparing audience response inside the Sala Grande, where the festival premieres were held, with those right behind the Palazzo, in a massive outdoor movie stadium called the Arena — frequented mainly by teenagers, who saw the same movies a night or two later. In contrast with the respectful silence greeting films by Rouch and Miklos Jancso at their indoor showings, loud peals of derision could be heard when they played at the Arena, where many spectators were waiting impatiently for the glossier new movies by Bertolucci and Pontcorvo to come on.

On the other hand, it would be hard to describe the outdoor screenings as any less formal than those inside the Palazzo. Flanked by tall, magisterial trees and multicolored fountains which sprang into action whenever the houselights came on, the Arena — reportedly built by Mussolini around the same time that he was helping to inaugurate the world’s first film festival in 1932 — had all the pomp and circumstance of a sports arena, even while showing The Wanderers and More American Grafitti.

In the final afternoon session, one loquacious Italian journalist complained that the conference itself was already a consumer product: “Everything is being produced here, even consumption.” As the scheduled talks relentlessly continued into the evening, documentary filmmaker Richard Leacock noisily protested the absence of any discussion. “All one way, like a television set!” he declared heatedly, gesturing at the podium, and left the conference with a few other disgruntled Americans.

***

Admittedly, the podium did appear to be strenuously overbooked at times. And considering the fact that the Babel of tongues and earphones made group solidarity almost impossible — no one could tell a joke and expect everyone to laugh at once — a certain amount of perpetual confusion was inevitable.

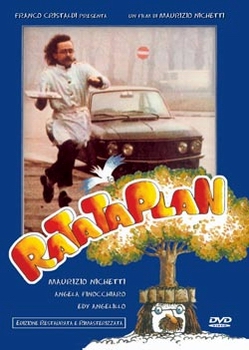

In these terms, perhaps the brightest revelation that I encountered in Venice was a wild farce about the modern world called Ratataplan — a brilliant first feature that quickly became a popular favorite at the festival. Written and directed by Maurizio Nichetti (who also stars as a shy, unassuming cafe waiter named Colombo), this weird succession of screwball skits — decked out with an onomatopoeic title based on the sound of a drum cadence — probably suggested more about cinema in the eighties than any of the lectures I heard.

In one sequence, a participant at an unidentified international conference in a skyscraper suffers a heart attack, and Colombo — operating a refreshment stand on a hilltop on the other side of the metropolis — is summoned by phone to bring this poor man a glass of mineral water. Colombo goes hurtling down the hill with his tray, and his involved journey across the city — during which his glass of water gets sprayed by exhaust fumes, covered by a policeman’s cap, and speckled with white paint before a bee unceremoniously drowns in it — becomes an epic, absurdist poem about contemporary urban life.

Later, this poem takes on a nightmarish tone as Colombo puts together a robot duplicate of himself inside his tenement flat, out of odds and ends from the city dump, including a video camera inside the headpiece. Guiding his suave, remote-control double out the door with a fixed steering wheel, like a puppeteer, and picking up its precise point of view in a television monitor, Colombo promptly gets his robot to score with the girl downstairs and take her out disco dancing.

Evoking at times a Clair, Tati, or Fellini crossed with some of the madder literary whimsy of a Sterne, Carroll, or Gogol (and a dash or so of Jerry Lewis), Nichetti seems too distinctively his own man to suggest anyone else for long. And it’s clearly too soon to know whether Ratataplan is an inspired fluke or the birth of a major talent. That’s one of the questions that the cinema in the eighties, in Venice and elsewhere, can hopefully answer — assuming that it’s still alive and kicking, as it was at the Biennale.