From the Spring 1982 Sight and Sound. — J.R.

Jack Reed’s Christmas Puppy: Reflections on REDS

1: On the Unreliability of Memory

Men make their own history, but they do not make it just as they please; they do not make it under circumstances chosen by themselves, but under circumstances directly encountered, given and transmitted from the past. — Karl Marx, The Eighteenth Brumaire

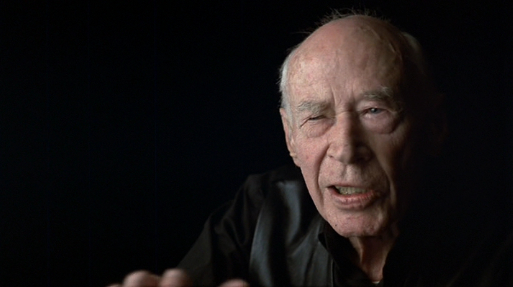

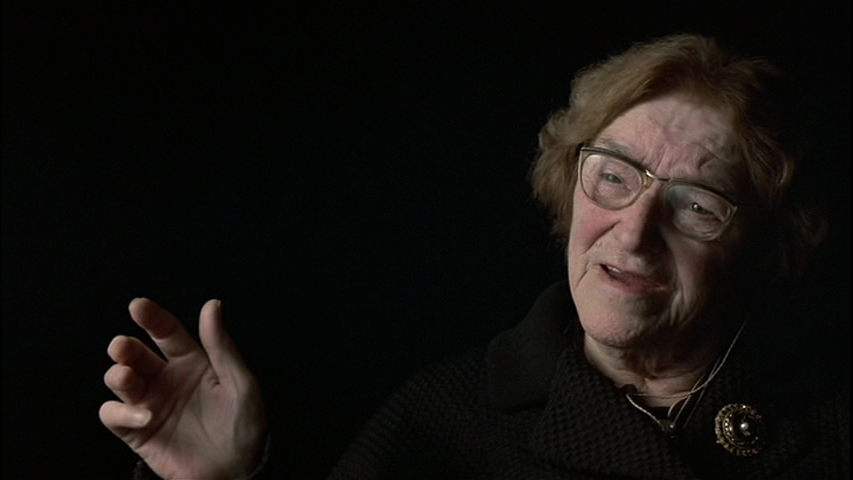

“Was it 1913 or ’17?” wonders the first ancient voice, male and faltering, after a burst of vigorous ragtime has faded out, before the opening credits have left the screen. “I can’t remember now — I’m beginning to forget all the people I used to know.” “Do I remember Louise Bryant?” asks the voice of another male oldster. “Why, of course; I couldn’t forget her if I tried.” A third witness of that period, female, appears on the right of the screen against a black background, lit like a Richard Avedon portrait. “I can’t tell you,” she replies to an unheard question. “I might sort of scratch my memory, but not at the moment . . . you know, things go and come back again.”

At once the conscience and the Greek chorus of REDS, the thirty-two “witnesses” who prattle and reminisce about the real characters and events — John Reed, Louise Bryant, Eugene O’Neill, Emma Goldman, World War I, the Russian Revolution — are immediately perceived as human, charming, and indispensable; without them, the film and its achievement could not even begin to exist. Like the gaggle of gossiping locals who occupy the foreground of several pivotal shots in Orson Welles’s THE MAGNIFICENT AMBERSONS, they embody the sense of community and popular wisdom that the film defines itself in relation to — the multifaceted oral history that paradoxically buries the characters at the same time that it keeps them alive for us.

Yet from the outset, the fallibility of these survivors is stressed as much as their reliability. Later on, they will contradict one another (on matters as disparate as John Reed’s talent as a poet and U.S. involvement in World War I), get names wrong and exhibit other confusions, refuse to speak or speculate on certain matters (“I’m not a purveyor of neighborhood gossip, nossir, that’s not my job”); but here they are already bearing witness to their shortcomings — sometimes knowingly, sometimes not. One witness worries about the correct Greenwich Village location: “It was Christopher Street, and I was thinking about another street down there instead. . . . Sometimes I have lapses like that.” Another virtually places political affiliation in the realm of irrelevance: “I’ve forgotten all about it. Were there socialists? I guess there must have been, but I don’t think they were of any importance — I don’t remember them at all.” Still another shrugs off the importance of romantic entanglements: “I know that Jack went around with Mabel Dodge, and then went around with another gal, and then went around with Louise Bryant. . . . It never impinged on my own personal life: I like baseball.”

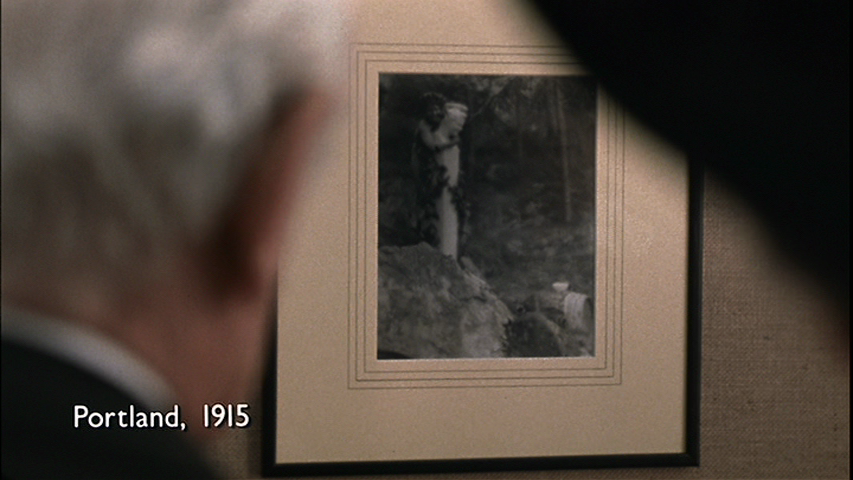

It is within such parameters that Warren Beatty situates his own history and audience, his own appeals to us. And while it might enhance our pleasure in some cases if each of the witnesses were identified when he or she is speaking — so that we would all know, for instance, that the codger commenting about sexual attitudes in the 1910s is Henry Miller, the one in a World War I outfit singing “Over There” is George Jessel, and the fellow who good-naturedly mutters “I urged the deportation of all alien Commonists [sic]” is Hamilton Fish — the absence of their names during their appearances can be justified strategically and aesthetically. Surely the fact that some participants are well known (Rebecca West, Will Durant) while others are not (acquaintances of Reed and Bryant in Portland) is less important than the democratic equality their anonymity grants them: they are here dialectically, as real contemporaries of the fictionalized characters, not as stars. And the fact that the rest of the movie already tends to keep us busy spotting the historical names — whether these are Floyd Dell or Aleksandr Kerensky (played, apparently, by a relative, Oleg Kerensky, who doubles as a witness), Max Eastman or Leon Trotsky — suggests that name tags here would create a cluttered effect.

In one of the several graceful rhyme effects established by Beatty between the United States and Russia in the fictive, “Hollywood” parts of the film, the question of John Reed’s “credentials” allowing him to speak at a political rally comes up twice: at an American Socialist party meeting in 1916, when he espouses war resistance (and is told he has no credentials, being a mere journalist), and at a revolutionary assembly the following year in Petrograd, when he expresses the solidarity of American workers (and is told that he needs no credentials, that everyone present has them). The essential fact about all the witnesses is that, in the final analysis, they have no credentials beyond what we see and hear of them — which proves to be more than enough. For all their individual memory lapses, their proximity in time to the people and events depicted in REDS — which camera and microphone suffice to reveal — gives them an authenticity to which the remainder of the film can’t pretend to aspire.

Collectively, they assume the role of the film’s narrator, the guiding consciousness and authorial voice that traditionally needs no name in third-person narrative. At the same time, they foreground the issue of their unreliability as individual commentators, creating a dispersed texture that is quite different from the unilateral continuity and supposed truth of, say, Welles’s impersonal third-person narration in AMBERSONS. Critics, of course, can be forgetful, too; when Pauline Kael argues, “In technique, REDS is the least radical, the least innovative epic you can imagine,” she can’t be remembering the witnesses, or Beatty’s use of them.

2: On the Unreliability of Hollywood

“Paramount Has Made a Communist Propaganda Epic” trumpeted the headline to an outraged editorial in Barron’s (December 14, 1981), but not many other critical commentaries to date appear to share this worry. Even Ronald Reagan, after attending a presidential screening with Beatty and Diane Keaton, reportedly said something to the effect that the film shows up the communists for what they are. Between his response and the Barron’s editorial looms the whole knotty problem of accepting the premise of the “revolutionary” blockbuster even theoretically. (Given the sources of financing — including a novel arrangement with Barclays’ Mercantile Industrial Finance Ltd, inspired by British tax law, whereby the film was sold prior to release and then leased back — as well as anticipated revenues, it’s difficult to conceive of an investment that knowingly betrays those interests.) The curious notion that Hollywood or its European counterparts could produce a truly and unequivocally progressive spectacle — what one might call the RED BALLOON fallacy, recalling the title of Serge Toubiana’s review of 1900 in Cahiers du cinéma — continues to be as much a facet of Hollywood myth and its policy of containment as it is a popular utopian leftist dream.

The utopian idealism of John Reed himself, however, was in many ways compatible with such a dream. According to his biographer, Robert A. Rosenstone, the Paterson Pageant organized by Reed for the IWW silk strike, held at Madison Square Garden in 1913, two years before the action of REDS begins, “diverted attention from the central issues,” namely, “hours and wages,” and the long-range overall effect it had on the strike was disastrous. (In fairness to Reed, it might be said that he learned from such blunders, and grew substantially in political maturity afterward.) So, too, one might protest that Beatty drains the real politics out of Reed’s life — the issues of class and revolution — for the sake of their traditional Hollywood replacements, romance and spectacle.

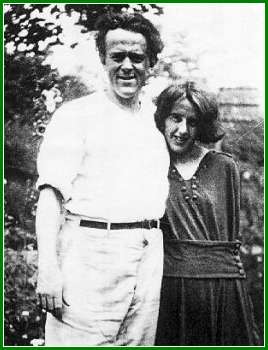

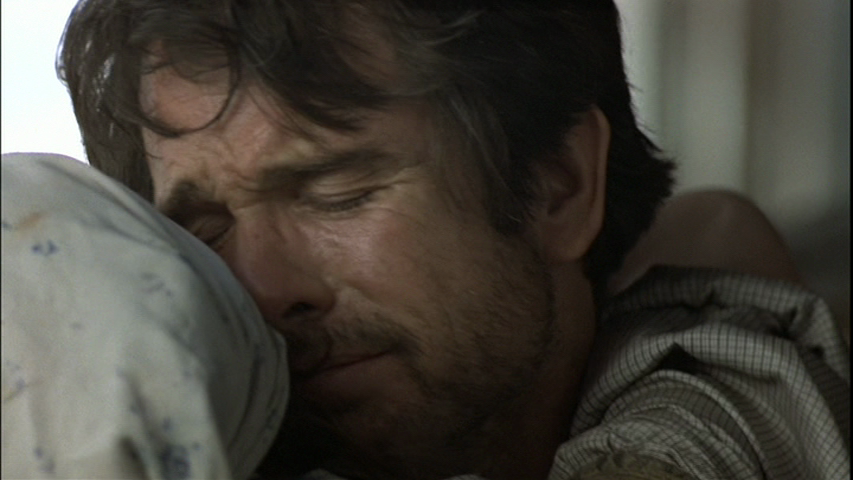

According to this argument, the radical lifestyles of Reed and Bryant are either diluted beyond recognition (by such things as severely limiting the degree of promiscuity practiced by both) or subsumed into sentimental Norman Rockwell magazine covers of cozy domesticity in New York, Provincetown, and Croton. Thus the gift-wrapped puppy given by Jack to Louise under one of the film’s many Christmas trees undermines their rhetoric about free love as effectively as the adorable Russian tot briefly encountered by Louise in the hospital during the final scene, wistfully standing in for the child they never got around to having. Both are characteristic emblems of the narcissism projected by Hollywood stars like Beatty and Keaton. Significantly, Jack Nicholson as Eugene O’Neill — in what might well be his best and most delicately shaded performance since EASY RIDER — establishes himself more sharply as an erotic presence than either of the leads. He shares this quality, moreover, with Jerzy Kosinski as Grigory Zinoviev, whose role in the film also challenges the Reed-Bryant relationship, but from the left rather than the “apolitical” right.

Central to the Hollywood cosmetics job performed on history is the treatment of Louise Bryant and the performance of Diane Keaton — separate but related issues in the film’s overall strategies. Regarding the former, Beatty’s use of Bryant as the principal identification figure — a partial equivalent to the semifaceless reporter Thompson in CITIZEN KANE, following in the wake of a mysterious, heroic myth (Reed) and pulling the audience along with her as she goes — severely limits the character as a representation of the real Louise Bryant.[*] Regarding the latter, it is worth noting the widespread dissatisfaction with Keaton in REDS that is currently being expressed, at least in the United States. In a Washington, D.C., cinema, during Bryant’s (fictional) trek across Finland in search of Reed, a skeptical spectator reportedly sang out “La-dee-da,” Keaton’s tagline as Annie Hall, to loud laughter and applause — suggesting part of the nature of the problem.

One might compare this response to the disaffection of the public with the character of the film director played by Jean-Pierre Léaud in LAST TANGO IN PARIS. In both cases, a formerly indulged romantic icon — New Wave adolescent cinéphile, flighty and eccentric star — becomes stale, loses conviction and glamour. And the superimposed hints of Keaton’s characters in ANNIE HALL, INTERIORS, and MANHATTAN, whether willed or not, saddles Bryant with the contemporary tics of a Woody Allen heroine, making the character less than ideal as a credible leftist model. As Veronica Geng has aptly noted, “The movement in her face reflects a mind that’s a garden of second thoughts; as soon as she asserts something, she takes it back,” so that her “outbursts in REDS are prime artifacts of feminist confusion.”

Such problems are perhaps only to be expected in a Hollywood framework whose invitations for identification are largely predicated on the necessity of describing the late 1910s in terms of the late 1960s (and afterward). And the collapse of these periods into one another is no doubt responsible for the relatively short shrift paid to such matters as class difference: as important as this was in Reed’s life and development, it finds few correspondences in the student revolts of the 60s, which were essentially a middle-class phenomenon. (The fact of Reed’s upper-class and Harvard background clearly played a role in his charisma, but although Upton Sinclair once irritated him by referring to him as “the playboy of the social revolution,” closer study of his career reveals him to be anything but a dilettante. In “A Taste of Justice” [1913], a brief but powerful story included in the collection Adventures of a Young Man, he describes with shocking candor the privilege he enjoys as a celebrity in relation to a prostitute facing a charge in a Manhattan night court.)

3: On the Importance of John Reed

As soon as the winter of the armoury show was over Mabel Dodge came back to Europe and brought with her what Jacques Emile-Blanche called her collection des jeunes gens assortis, a mixed assortment of young men. In the lot were Carl Van Vechten, Robert Jones and John Reed . . . . I remember the evening they all came. Picasso was there too. He looked at John Reed critically and said, le genre de Braque mais beaucoup moins rigolo, Braque’s kind but much less diverting. I remember also that Reed told me about his trip through Spain. He told me he had seen many strange sights there, that he had seen witches chased through the streets of Salamanca. As I had been spending months in Spain and he only weeks I neither liked his stories nor believed them. — Gertrude Stein, The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas

Reed was a westerner and words meant what they said.

The war was a blast that blew out all the Diogenes lanterns;

the good men began to gang up to call for machine guns. Jack Reed was the last of the great race of war correspondents who ducked under censorships and risked their skins for a story.

Jack Reed was the best American writer of his time, if anybody wanted to know about the war they could have read about it in the articles he wrote

about the German front,

the Serbian retreat,

Saloniki;

behind the lines in the tottering empire of the Czar,

dodging the secret police, jail in Cholm. — John Dos Passos, “Playboy” (in 1919)

As I look back on it all, it seems to me that the most important thing to know about the war is how the different peoples live; their environment, tradition, and the revealing things they do and say. In time of peace, many human qualities are covered up which come to the surface in a sharp crisis; but on the other hand, much of personal and racial quality is submerged in time of great public stress. And in this book [illustrator Boardman] Robinson and I have simply tried to give our impressions of human beings as we found them. — John Reed, The War in Eastern Europe (1916)

Considering how far John Reed actively sought to become a legend during his own lifetime, it hardly seems surprising that so many accounts of him — including the first two cited above, written at almost precisely the same time half a century ago, in 1932 — differ so strikingly. As the first of the novelistic journalists — a breed of macho adventurer that would later include Hemingway and Mailer (both, as it happens, third-rate poets like Reed when it came to affecting Kipling-style doggerel) as well as Orwell — Reed still serves to embody the active, committed reporter in opposition to the armchair analyst. If memory serves, it is just this image that informs Paul Leduc’s Mexican film REED: MÉXICO INSURGENTE (1969), shot documentary-style in sepia, which concludes with a freeze-frame of Reed breaking a shop window to steal a camera; it is certainly the spirit that underlies Reed’s own Ten Days That Shook the World.

By insisting throughout on the fusion of the personal with the political, REDS postulates as a fundamental aspect of its seductive appeal that spectators perform something of the same synthesis, within the terms of their own psychological, sexual, and political chemistries — forging their own personal links and private bridges between the recent 1960s and the remote 1910s, with the elderly witnesses officiating like partial and informal guides in these subtle and delicate transactions. As suggested above, Beatty’s singular stroke of brilliance in using these mediators is to create a form of dialectics, a kind of dialectical play of historical analysis, which to a limited (if invaluable) degree authenticates and objectifies two otherwise debatable positions: the forgetful personal account and the nostalgic Hollywood myth. Thus two forms of sentimentality and unreliability complement and challenge one another, across a canvas comprising five years and six locations (less than a sixth of Reed’s life), in the separate titled panels of the movie: Portland, 1915; Croton-on-Hudson, 1916; Paris, 1917; New York, 1918; Chicago, 1919; Petrograd, 1920. From their conjunction and juxtaposition comes a certain kind of honesty, a modest yet workable access to truth.

The occasional use of overlapping voices on the sound track (mainly Beatty’s or Keaton’s) serves to remind one how much of the film’s narrative structure and use of incidental detail is based on principles of overlap between documentary and fiction, between sex or art and politics. The period song “I Don’t Want to Play in Your Yard” — as relevant to personal borders as one wants to make it — is first sung by a male witness, then taken up by the orchestra on the sound track before being resumed by Louise, singing it to O’Neill and others in Provincetown (in Jack’s absence, shortly after her affair with Eugene has begun), where it takes on a decidedly sexual resonance. Conversely, the performance of the “Internationale” by a Russian chorus just before the film’s intermission, when Reed and Bryant’s encounter with the Russian Revolution is unmistakably linked to their orgasmic sexual reunion in Petrograd, is followed, just after the interval, by one of the female witnesses singing the same song in English.

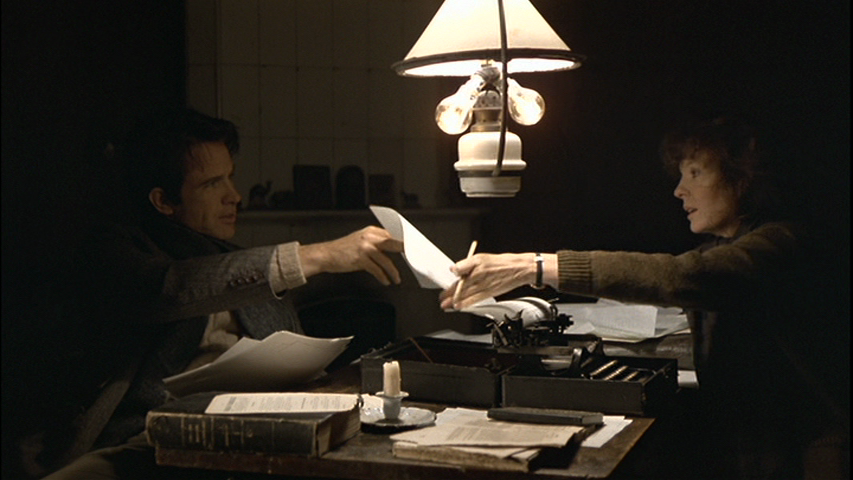

By the same token, two emblematic objects spanning separate scenes are O’Neill’s unopened love letter to Bryant, pressed between pages of Leaves of Grass, and Reed’s unfinished poem on the back of an IWW flyer — each reflecting the untidy, giddy overlays of energetic, incomplete lives caught up in external events. Many of the masterful early scenes seem constructed around comparable notions of superimposed layers involving sound and image: Emma Goldman (superbly played by Maureen Stapleton) introduced from Louise’s viewpoint as a chattering offscreen voice entering Reed’s Village flat; an argument in the same place on a rainy afternoon (all mottled patterns and flickering shadows in Vittorio Storaro’s beautifully textured tones); a skillful evocation of a Bohemian community in Provincetown executed in simple, consecutive strokes effectively blended together, like some of the atmospheric mixes of vacation-time impressions that open SUNRISE. A montage of Greenwich Village social gatherings at which Louise comically strives to establish her own credentials directly evokes, for that matter, the speeded-up account of Charles Foster Kane’s first marriage, with its own use of overlapping breakfasts. But if KANE is recalled at many junctures throughout REDS, it is worth noting the political difference that KANE views journalism more from the vantage point of management than from that of labor.

If REDS reaches a political conclusion of any sort, this may be the recognition that certain events, like certain lives, invariably get lost in (or devoured by) history, but collective struggle and romantic love are not necessarily strange bedfellows. One of the more striking rhyme effects has Reed angrily declaring, “You don’t rewrite what I write” — initially to a New York editor (Gene Hackman), later to Kosinski’s Zinoviev. And the climatic framing rhyme of Jack proposing to Louise that they go to New York together — first from Portland in 1915, shortly after they’ve met; then from Petrograd in 1920 — raises the question each time of what they are to go as. Lovers or comrades? The film’s efforts to collapse these categories into one are as idealistic and courageous, in a way, as Reed and Bryant were themselves, as touching and as serious and as foolhardy.

As the witnesses once again take over the narrative reins, continuing behind the final credits, a synthesis of old and new commentaries paradoxically leaves us with the same doubts and yet with firmer commitments, stronger beliefs. “I’ve forgotten all about it. Were there socialists?” ” . . . I don’t remember his exact words, but the meaning was that great things are ahead, worth living and worth dying for. He himself said that.” — Sight and Sound, Spring 1982

[*] According to Laura Cottingham (“What REDS Won’t Tell You About Louise Bryant,” Soho News, December 22, 1981), Bryant was somewhat more substantial as an independent thinker and journalist than the movie suggests. A recently reprinted excerpt from her 1918 book Six Red Months in Russia seems to bear this out.