From Sight and Sound, Winter 1982/1983, and reprinted in my collection Placing Movies. It was initially commissioned by Peter Biskind for American Film, who decided not to run it and paid me a kill fee, so I sent it next to Penelope Houston, who accepted it without hesitation. Originally, this piece was designed to be run with my translation of a brief, early piece by Barthes (“Au Cinemascope,” originally published in Les Lettres Nouvelles, February 1954). To my frustration, after Sight and Sound secured the rights to run this piece, they wound up omitting it due to lack of space, but it has subsequently appeared online in at least two places: here and here (the latter on this site). — J.R.

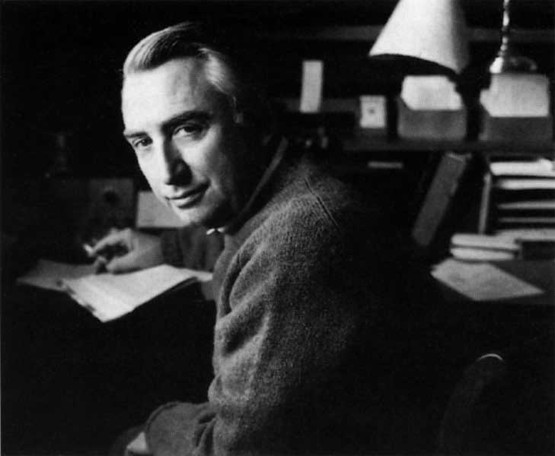

One reason for looking at the late Roland Barthes’ writings about film is that we all tend to be much too specialized in the ways that we think about culture in general and movies in particular. Far from being a film specialist, Barthes could even be considered somewhat cinephobic (to coin a term), at least for a Frenchman. Speaking to Jacques Rivette and Michel Delahaye in 1963, he confessed, “I don’t go very often to the cinema, hardly once a week” — inadvertently revealing the French passion for movies that can infect even a relative nonbeliever.

Cinephobic? Perhaps. He certainly mistrusted the hypnotic spell exerted by cinema and the attendant problem, for an analyst, of having to reconcile this continuity of appeal with a discontinuity of what he called signs. Yet what he had to say about literature, theater, photography, and music (his first loves) may wind up telling us more about film than the entire output of many movie critics. And what Barthes had to say about cinema — both in general and in many specific cases — is often interesting enough in its own right.

***

Movie Problems

“Resistance to the cinema . . . ” he wrote in the self-regarding Roland Barthes (1975), trying to get a fix on what he didn’t like about the medium. “Without remission, a continuum of images; the film. . .follows, like a garrulous ribbon: statutory impossibility of the fragment, of the haiku.” A lover of the fragment and the haiku, he possibly came closest to analyzing a film when he devoted an essay (“The Third Meaning”) to a few stills taken from Eisenstein’s IVAN THE TERRIBLE. He virtually began his last book, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography, with the admission that “I decided I liked photography in opposition to the cinema, from which I nontheless failed to separate it.”

Nor was this his only problem with movies. As he went on to say in Roland Barthes, “Constraints of representation (analogous to the obligatory rubrics of language) make it necessary to receive everything: of a man walking in the snow, even before he signifies, everything is given to me; in writing, on the contrary, I am not obliged to see how the hero wears his nails — but if it wants to, the Text describes, and with what force, Hölderlin’s filthy talons.” The trouble, in short, was that film — that “festival of affects,” as Barthes called it — offered the spectator too much, yet not enough.

***

A Late Starter

Born in 1915, Barthes didn’t publish his first book, Writing Degree Zero, until he was thirty-seven. He suffered from pulmonary tuberculosis for much of his youth and published his first articles (1942–1944) in a magazine put out by the Sanitorium des Étudiants, where he was staying much of the time. I haven’t been able to track down the third of these pieces — a review of the first feature directed by Robert Bresson, LES ANGES DU PÉCHÉ.

Barthes apparently didn’t deal with film again until about 1954, when he started to write a series of magazine articles that eventually became grouped together under the heading “Mythologies.” This involved writing about all kinds of cultural activity, ranging from wrestling to striptease to tourist guides, in which films were allowed to play a significant part. In the course of developing this approach — initially with the aid of semiology, and later with the help of psychoanalysis — he constructed a critique of cinema that took shape in such essays as “The Third Meaning” (1970) and “Upon Leaving the Movie Theater” (1975).

In the late 1970s, not long before his death, Barthes agreed to play the novelist William Thackeray in his friend André Téchiné’s film THE BRONTË SISTERS. (He had earlier refused to play himself in Godard’s ALPHAVILLE in 1965.) And after that, he even contemplated writing a film script which Téchiné would direct, based on the life of Marcel Proust.

***

Hair, Sweat, & Semiology

Contemporary resistance to semiology as a dry academic pursuit can’t be dealing with the spirited polemical and political use of it made by Barthes as a journalist over a quarter of a century ago, when he was defining and attacking current mythologies in the pages of Les Lettres Nouvelles. Semiology — a term and concept first formulated by linguist Ferdinand de Sanssure in the early years of this century, when he called for a “science that studies the life of signs within society” — was in fact brought to the attention of a wide public largely through Barthes’ efforts.

Inaugurating the chair of Literary Semiology at the Collège de France in the late 1970s, Barthes reminded his audience that:

Semiology, so far as I am concerned, started from a strictly emotional impulse. It seemed to me (around 1954) that a science of signs might stimulate social criticism, and that Sartre, Brecht, and Saussure could concur in the project. It was a question, in short, of understanding (or of describing) how a society produces stereotypes, i.e., triumphs of artifice, which it then consumes as innate meanings, i.e., triumphs of nature. Semiology (my semiology, at least) is generated by an intolerance of this mixture of bad faith and good conscience which characterizes the general morality, and which Brecht, in his attack upon it, called the Great Habit.

In “The Roman in Films” (1954), some of these stereotypes, as evidenced in Joseph L. Mankiewicz’s film of JULIUS CAESAR, turn out to be fairly amusing. For instance, Barthes notices that all the male characters in the film sport fringes in order to demonstrate that they are Romans:

We therefore see here the mainstream of the Spectacle — the sign —operating in the open. The frontal lock overwhelms one with evidence, no one can doubt that he is in Ancient Rome. And this certainty is permanent: the actors speak, act, torment themselves, debate “questions of universal import,” without losing, thanks to this little flag displayed on their foreheads, any of their historical plausibility. Their general representativeness can even expand in complete safety, cross the ocean and the centuries, and merge into the Yankee mugs of Hollywood extras: no matter, everyone is reassured, installed in the quiet certainty of a universe without duplicity, where Romans are Romans thanks to the most legible of signs: hair on the forehead.

From this observation, Barthes goes on to trace two intriguing “subsigns” in the film: (1) “Portia and Calpurnia, woken at dead of night, have conspicuously uncombed hair,” and (2) “all the faces” in the film “sweat constantly,” a sign of “moral feeling.” (“To sweat is to think — which evidently rests on the postulate, appropriate to a nation of businessmen, that thought is a violent, cataclysmic operation, of which sweat is only the most benign symptom.” Hence, Caesar himself, “the object of the crime,” is the only man in the film who remains dry.)

***

A Galaxy of Stars, A Plurality of Texts

On the subject of stars, Barthes had many intriguing things to say. Four months after his bout with JULIUS CAESAR, he was decrying the excessive use of movie stars in Sacha Guitry’s SI VERSAILLES M’ÉTAIT CONTÉ:

In the final analysis, the star system is not without a kind of chicanery: it consists of popularising History by Cinema, and of glorifying Cinema by History. It’s a form of barter judged useful by both powers: for instance, Georges Marchal passes a little of his erotic glory over to Louis XIV, and in return, Louis XIV surrenders a little of his monarchical glory to Georges Marchal.

Barthes went on to reproach Guitry for not taking a lesson from the costume styling of the Folies Bergère, where the forms of period dress are false but “superbly so, with a fine contempt for accuracy and a desire to give fancy dress an epic dimension.”

The same year, he praised Charlie Chaplin as a Brechtian artist, showing “the public its blindness by presenting at the same time a man who is blind and what is in front of him,” that is, “a kind of primitive proletarian, still outside Revolution” in MODERN TIMES . Twenty-five years later, in a regular column he was writing for Le Nouvel Observateur, he expressed his fascination with an image from LIMELIGHT— Chaplin applying makeup in front of a mirror — as “literally a metamorphosis, such as only mythology and entomology could speak about it.” And a few years before that, writing about himself in the third person in Roland Barthes, R. B. had this to say:

As a child, he was not so fond of Chaplin’s films; it was later that, without losing sight of the muddled and solacing ideology of the character, he found a kind of delight in this art at once so popular (in both senses) and so intricate; it was a composite art, looping together several tastes, several languages. Such artists provoke a complete kind of joy, for they afford the image of a culture that is at once differential and collective: plural. This image then functions as the third term, the subversive term of the opposition in which we are imprisoned: mass culture or high culture.

Writing poetically about the face of Greta Garbo — that mythic object par excellence — the same year, Barthes found that it represented a “fragile moment when the cinema is about to draw an existential from an essential beauty, when the archetype leans towards the fascination of moral faces, when the clarity of the flesh as essence yields its place to a lyricism of Woman.” Comparing her face to the more individualized face of Audrey Hepburn, he concluded that, “As a language, Garbo’s singularity was of the order of the concept, that of Audrey Hepburn is of the order of the substance. The face of Garbo is an Idea, that of Hepburn, an Event.” The preceding translation is by Annette Lavers. When another Barthes translator, Richard Howard, published his own version of this essay in the 1960s, this formulation was updated by substituting Brigitte Bardot for Audrey Hepburn, leading to a more topical closing line: “Garbo’s face is an Idea, Bardot’s a Happening.”

***

I Didn’t Know the Gun Was Coded

There’s another way of looking at Barthes and film, less poetic, that has been favored by certain academics. This involves seeing him as a great system builder, whose famous phrase by phrase textual analysis of a novella by Balzac called Sarrazine, a study known as S/Z, breaks down “the realist text” into “five levels of connotation” or “codes.” From the methodology of analyzing prose narrative — which Barthes derived collectively from one of his seminars — certain film academics have tried to establish a more systematic approach in studying movies.

Without wishing to dismiss this sort of work, I can’t say I’ve found it as useful as Barthes’ more poetic and suggestive (if less systematic) writings. Maybe this is because I value his work more for its questions than its answers, and more for its art (and play) than its science (and work). In this respect, stylistically and iconoclastically, Barthes is closer to an American film critic like Manny Farber — above all, in the peculiarly cinematic flux, speed, and movement of his thought — than he is to fellow French semiologists like Raymond Bellour and Christian Metz.

One could also argue that the more “teachable” an analytic approach is, the easier it becomes to apply it mechanically — as, indeed, a generation of graduate students and professors has often tended to apply S/Z, without much thoughtfulness or insight.

***

Art as Immobility

Ideology is, in effect, the imaginary of an epoch, the Cinema of a society. — “Upon Leaving the Movie Theater”

In 1959, when the French New Wave was just beginning to make itself felt, Barthes published a critique of Claude Chabrol’s first film, LE BEAU SERGE, which called it right-wing for imposing a static image of man. The same year, in Cahiers du Cinéma, Chabrol wrote, “There’s no such thing as a big theme and a little theme, because the smaller the theme is, the more one can give it a big treatment. The truth is, truth is all that matters.” The problem about this position for Barthes was that it led to political complacency. The offhand way one looked at someone or something, he wrote, could become “the basis for an act of sarcasm or one of tenderness, in short, a truth,” but the offhand way one arrived at a theme could be a falsehood. “What is terrible about the cinema,” he added, “is that it makes the monstrous viable; one could even say that currently our entire avant-garde lives on this contradiction: true signs, a false meaning.”

Summing up what he liked in Chabrol’s provincial melodrama as “micro-realism,” Barthes compared its “descriptive surface” — as in the gestures of children playing football in the street — with that of Flaubert. “The difference — which is considerable — is that Flaubert never wrote a story.” Flaubert had the insight to realize that the ultimate value of his realism was its insignificance, “that the world signified only that it signified nothing.”

Chabrol, on the contrary, his realism firmly in place, invests a pathos and a moral — that is to say, whether he wills it or not, an ideology. There are no innocent stories: for the past hundred years, Literature has been struggling with this calamity.

For Barthes, Chabrol’s “art of the fight” always assigned meanings to human misfortunes without examining the reasons:

The peasants drink. Why? Because they’re very poor and have nothing to do. Why this misery, this abandon? Here the investigation stops or becomes sublimated: they are undoubtedly stupid in essence, it’s their nature. One certainly isn’t asking for a course in political economy on the causes of rural poverty. But an artist should acknowledge his responsibility for the terms he assigns to his explanations: there is always a moment when art immobilises the world, and the later it comes, the better. I call art of the right this fascination with immobility, which makes one describe outcomes without ever asking about, I won’t say causes (art isn’t deterministic), but functions.

***

Buñuel Versus Chabrol

Four years later, interviewed by Cahiers du Cinéma, Barthes pursued this notion further by evoking an art which challenged ideology by suspending meaning — a development in some ways of Brecht’s ideas about alienation and New Novelist Alain Robbe-Grillet’s ideas about nonhumanistic art:

What I ask myself now is if there aren’t arts which are more or less reactionary by their very natures and techniques. I believe that of literature; I don’t believe a literature of the left would be possible. A problematic literature, yes — that is, a literature of suspended meaning: an art which provokes responses but doesn’t supply them. I think literature is that in the best of cases. As for cinema, I have the impression that, in this respect, it’s very close to literature, and because of its structure and material, it’s a lot better prepared than theatre is for a certain responsibility for forms that I’ve called the technique of suspended meaning. I think cinema has trouble supplying clear meanings and that, in its present state, this shouldn’t be done. The best films (for me) are those that suspend meaning the most…. an extremely difficult operation, requiring at once great technique and total intellectual honesty. For that means disentangling oneself from all the parasite meanings . . .

As a prime example of what he meant, Barthes cited Luis Buñuel’s recent THE EXTERMINATING ANGEL— a brilliant comic horror film about wealthy guests who inexplicably find themselves incapable of leaving a dinner party. Here, Barthes said, meaning was deliberately suspended without becoming nonsensical or absurd, in a film that jolted one “profoundly, beyond dogmatism, beyond doctrines.” In the vulgar but accurate sense, it was a film that “made one think.”

A few years later, Barthes’ notion of suspended meaning would develop still further into two major utopian, cultural models. In his beautiful Empire of Signs (1970), Barthes posited Japan and its culture as a system consisting of the “play” of “empty” signs — a concept that was crucially to influence Noël Burch when the latter wrote his history of Japanese cinema, To the Distant Observer. And in The Pleasure of the Text (1973), this became the notion of a reader’s “bliss” as opposed to his or her “pleasure” in reading a text — the former a discontinuity of signs akin to the experience of sexual orgasm, when meaning again becomes suspended.

***

This Way, Myth

Passing references to films in Barthes’ writings form a significant part of their overall color and texture. Describing the mythical properties of the new Citroën in 1955, he saw it “originating from the heaven of METROPOLIS.” The same year, stirred in part by Jacques Becker’s TOUCHEZ PAS AU GRISBI, he analyzed the “coolness” of gangsters in gangster films, marveling at the visual and nonverbal emphasis of their behavior, which insured that “each man regains the ideality of a world surrendered to a purely gestural vocabulary, a world which will no longer slow down under the fetters of language: gangsters and gods do not speak, they nod, and everything is fulfilled.” The next year, writing about the myth of exoticism revealed by a documentary about the Mysterious Orient, THE LOST CONTINENT, he noted the various means by which Buddhism was treated as “a higher form of Catholicism,” and dryly observed that, “Faced with anything foreign, the Established Order knows only two types of behavior, which are both mutilating: either to acknowledge it as a Punch and Judy show, or to defuse it as a pure reflection of the West.”

***

Barthes and Films

Sometimes a particular film could goad Barthes into a major formulation. For many readers, the key passage in The Pleasure of the Text is a paragraph that links storytelling to the myth of Oedipus. This was written, Barthes notes at the end, after having seen F. W. Murnau’s CITY GIRL — a silent Hollywood film of 1929 that had just been shown on French television. In Roland Barthes, he delighted in the “textual treasury” of a Marx Brothers movie, A NIGHT AT THE OPERA — including “the liner cabin, the torn contract, the final chaos of the opera décors” — as emblems of “the logical subversions performed by the Text.” In the same book, he compared the process of his own writing to a theater rehearsal in a film by Jacques Rivette (who, in turn, has spoken often of Barthes’ influence on his own work), a rehearsal that is “verbose, infinite . . . shot through with other matters.”

Later, in A Lover’s Discourse: Fragments (1978), he would cite a scene from Buñuel’s THE DISCREET CHARM OF THE BOURGEOISIE — a curtain rising “the wrong way round — not on an intimate stage, but on the crowded theater” — as an emblematic image for the painful revelation of commonplace information by a lover’s informer about his or her beloved. And in a magazine column in 1979, he recorded his distress at an audience laughing at the very things in Eric Rohmer’s PERCEVAL (like the hero’s simplicity) that he loved the most, and his amusement at seeing “a very French film,” VINCENT, FRANÇOIS, PAUL . . . AND THE OTHERS, on French television (“The stereotype here is nationalised; it forms part of the décor, not part of the story”).

***

Ugly Excess

In “The Third Meaning,” Barthes distinguishes three levels of meaning in the stills from IVAN THE TERRIBLE that he examines. The first is informational, on the level of communication, to be analyzed by semiology. The second is symbolic, on the level of signification, to be analyzed by “the sciences of the symbol (psychoanalysis, economy, dramaturgy).” The third, which Barthes calls the “obtuse meaning,” constitutes that surplus of meaning which can’t be exhausted by the other two.

This level of “excess” (as it has been called by film scholar Kristin Thompson) is the hardest to describe with any clarity, for most criticism, by equating a film with its story and interpretation, fails to acknowledge that this third meaning can exist on any level at all. Barthes finds it in his own subjective observations of such details as the ugliness of the character Euphrosinia, which “exceeds the anecdote, becomes a blunting of the meaning, its deflection”:

Imagine “following” not Euphrosinia’s machinations, nor even the character . . . nor even, further, the countenance of the Wicked Mother, but only, in this countenance, that grimace, that black veil, the heavy, ugly dullness of that skin. You will have another temporality . . . another film. A theme with neither variations nor development . . . the obtuse meaning can proceed only by appearing and disappearing.

On the Way Out

“Upon Leaving the Movie Theater” begins with Barthes’ description of how much he loves that curious activity, which he compares to coming out of hypnosis. Reflecting on the theater’s darkness and what it suggests to him — the “lack of ceremony” and “relaxation of postures” — he settles on the poetic image of the cocoon: “The film spectator might adopt the silk worm’s motto: inclusum labor illustrat: because I am shut in I work, and shine with all the intensity of my desire.”

Submerged in the darkness of the theatre (an anonymous, crowded darkness: how boring and frustrating all those so-called “private” screenings), we find the very source of the fascination exercised by film (any film). Consider, on the other hand, the opposite experience, the experience of television, which also shows films: nothing, no fascination; the darkness is dissolved, the anonymity repressed, the space is familiar, organised (by furniture and familiar objects), tamed. Eroticism — or, better yet, in order to stress its frivolity, its incompleteness, the eroticisation of space — is foreclosed. Television condemns us to the Family, whose household utensil it has become just as the hearth once was, flanked by its predictable communal stewing pot in times past.

Linking the ideological stereotype with the still image, Barthes wonders if we all don’t have “a dual relationship with platitudes: both narcissistic and maternal,” in psychoanalytic terms. And the only way to pry oneself from the mirror (i.e., the screen) is to break “the circle of duality/ . . . filmic fascination” and “loosen the glue’s grip, the hypnosis of verisimilitude” that is commonly referred to as suspension of disbelief. This can be done “by resorting to some (aural or visual) critical faculty of the spectator — isn’t that what is involved in the Brechtian distancing effect?”

Yet instead of going to movies “armed with the discourse of counterideology,” Barthes suggests another way. This involves letting himself become involved as if he had two bodies at once, one of them narcissistic, and the other one “perverse,” making a fetish not of the image but of what “exceeds” it: “The sound’s grain, the theatre, the obscure mass of other bodies, the rays of light, the entrance, the exit . . . ” The distance with respect to the image, he concludes, is finally what fascinates us — a distance which is not so much intellectual as “amorous” . . . And despite all the numerous quarrels with cinema that Barthes maintained over a quarter of a century of writing, one suspects that many of them, in the final analysis, were a lover’s quarrels, a lover’s discourse.

The author’s thanks to Stephen Heath, Michael Silverman, and Bérénice Reynaud.

— Sight and Sound, Winter 1982/1983