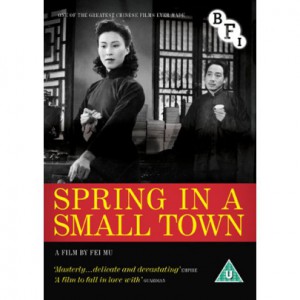

From The Guardian (June 6, 2003). Happily, Fei Mu’s 1948 masterpiece is now available on a decent DVD with English subtitles from the BFI, and I’ve recently written a lengthy essay about it for the final issue of the French quarterrly Trafic, to be published in French this fall and on this site in English around the sane time..– J.R.

If I had to pinpoint what makes so much of contemporary life intolerable, something I’d call remake mentality might head the top of the list. The mindset that dictates that anything new has to be a recycling of something familiar — that old markets be exhausted before any new ones are contemplated, and that viewers be regarded as mindless brats demanding only more of the same — is so common by now that it has become fully internalised, and not only within the film industry.

The fact that we’re supposed to be looking forward to two sequels to The Matrix in the same year implies that we are fixed marketing units, programmed to relish staying in our well-appointed ruts. But there are just as many spinoffs predicated on our ignorance of the originals, suggesting that the avoidance of fresh thinking may not simply be our own. So I had my share of worries when I first heard that one of my favourite Chinese film-makers, Tian Zhuangzhuang, the director of The Horse Thief (1985) and The Blue Kite (1992), was remaking a Chinese classic.

What I should have realised from the outset is that Tian has been reinventing himself throughout his career, by necessity as much as by design — a process that has stemmed in part from his political outspokenness, which has made it impossible for him to direct a film for the past decade. The fact that he is working again is already a blessing, and the fact that he is remaking a masterpiece doesn’t in this case mean any reversion to formula. For Chinese spectators, it represents both a formidable challenge and a way of re-situating the present in relation to the past. And for practically everyone else, it constitutes a new story that can fully stand on its own — even if it also introduces one to a locus classicus of Chinese cinema whose discovery in the west is long overdue.

It is one of those seemingly arbitrary yet symptomatic accidents of film history that Fei Mu’s 1948 Springtime in a Small Town is scarcely known at all outside the Chinese-speaking world. My first look at it was quite recent, and came about courtesy of Stephen Teo, a Chinese film critic in Melbourne — author of the indispensable Hong Kong Cinema: The Extra Dimensions (1997) — who taped it from Australian TV and sent me a copy in Chicago.

Discovering that it fully lives up to its reputation, I mentioned Springtime in a Small Town to a Chinese film buff I know in Chicago, who avowed that it was readily available at his own video rental outlet in Chinatown. Why, then, are English-subtitled versions so scarce? It’s almost as if some ideological divide far greater than any commercial considerations was keeping this masterpiece out of reach for anyone without a grasp of Mandarin.

Yet there is nothing inaccessible or “inscrutably” Chinese about a film that surely qualifies as a key inspiration for Wong Kar-wai’s In the Mood for Love (2000) — savoured without difficulty by non-Asians across the globe — as well as Tian’s no less approachable and inspired new version. Part of the problem is that Chinese film history itself tends to have been written in quicksand. (It is sadly emblematic that the original negative of Stanley Kwan’s luminous 1991 film The Actress, a biopic about the great Chinese silent screen actress Ruan Ling-yu — many of whose films were directed by Fei Mu, who figures as a character in the film — has already been destroyed, and that only a truncated version survives on DVD.) [February 2010 postscript: I’m delighted to report that this rumor isn’t true, and that the full version is now available on DVD.]

A highly charged erotic chamber drama about unfulfilled adulterous passion, Springtime in a Small Town, made one year before the communist victory in mainland China, is set in 1946, shortly after the Japanese retreat. It unfolds in and around the ruins of a mansion in the middle of nowhere in southern China that figures as the “city” of the Fei Mu original — and is part of a small town that we mainly intuit from the heroine’s reference to her daily shopping and the school her teenage sister-in-law attends, without ever actually seeing much of it.

The story features five characters. Dai Liyan, an ailing aristocrat who is the only surviving male in his family, spends most of his time brooding in the garden of his ancestral home, much of which has been reduced to rubble by Japanese bombs. He lives there with his kid sister Dai Xiu, his emotionally estranged but dutiful wife Yuwen — whom he married eight years before, shortly before the outbreak of war, and who now sleeps in a separate bedroom — and an elderly male servant.

Arriving unexpectedly on the train one day from Shanghai is an old college friend of Liyan’s, Zhang Zhichen, now a licensed doctor — and, unbeknown to Liyan, a former neighbour and the first sweetheart of Yuwen. Much of what follows proceeds by indirection and nuance as Zhichen and Yuwen negotiate the stirrings of their former passion. (Fei Mu reportedly solicited the exquisite performances from his leads by instructing them with the venerable Chinese saying: “Begin with emotion, end with restraint!”) On the eve of Xiu’s 16th birthday, Liyan suggests that the doctor would make a perfect husband for her once she becomes older, and after everyone gets drunk at the birthday celebration, many feelings rise to the surface, culminating in Liyan overdosing on sleeping pills.

There are certainly allegorical meanings that can be read into the plot involving class and social change, as well as the attitudes of three separate generations (as represented by the servant, the teenage sister and the other three characters) — meanings that had contemporary relevance to China in the late 1940s and still have relevance today. But Tian has stressed that the key meaning the story has for him is the warmth of the emotions that it expresses.

“What is sure is that some deep and true feelings are now waning away from people’s hearts,” he said in an interview with Robin Gatto last year. “And this is a problem for young people. They’re pretty confused. They have only vague, dim ideas about feelings, the development and nurture of human emotions. So what I found very interesting was to depict some feelings in my characters… What I wanted to analyse and what is very important for me is not the final results of their acts, but the way they deal with their feelings.”

The clearest stylistic bond between Fei Mu’s masterpiece and Tian’s remake is that both are propelled by a highly expressive mise en scène articulated by nearly constant camera movements that curve around the actors and settings, continually redefining their relationships. This mise en scène articulates the intense feelings that the characters can only allude to in isolated gestures — such as Liyan, in a temper tantrum, throwing down his medicine, or Yuwen, in frustrated passion, breaking the glass pane on a door separating her from Zhichen — key moments in both versions.

Perhaps the most striking difference is the modernist and poetic off-screen narration of Yuwen in the original — often recounting certain incidents that occur in her absence with telling selective details — which Tian discards entirely. Apart from this “objectification”, one of Tian’s main changes is to bring the doctor into the story sooner, situating his arrival on the train from Shanghai in the opening sequence, rather than introducing him only after the other characters have been fully established.

Although Liyan exudes a certain pathos as the stand-in for a decadent aristocracy on its last legs, and his sister figures as a kind of blank slate, it is part of the strength of this story that all five characters register as sympathetic. But the heart of the film’s passion rests in the barely expressed memories and longings of Zhichen and Yuwen, and there are few moments in Chinese cinema as intensely erotic as the scenes between the two in the guest room where Zhichen is staying.

Am I speaking now about Fei Mu’s version of those scenes, or about Tian Zhuangzhuang’s? I’m speaking about both. The most remarkable thing about Tian’s complex and wholly self-sufficient re-creation is how faithfully it honours its source without ever stooping to simple imitation or postmodernist “homage”. Reinventing his source just as boldly as he has reinvented his artistic identity, Tian manages to circumvent remake mentality by making his material brand new.