Written for an Arbelos Films Blu-Ray in 2024.

Two to Tangle

By Jonathan Rosenbaum

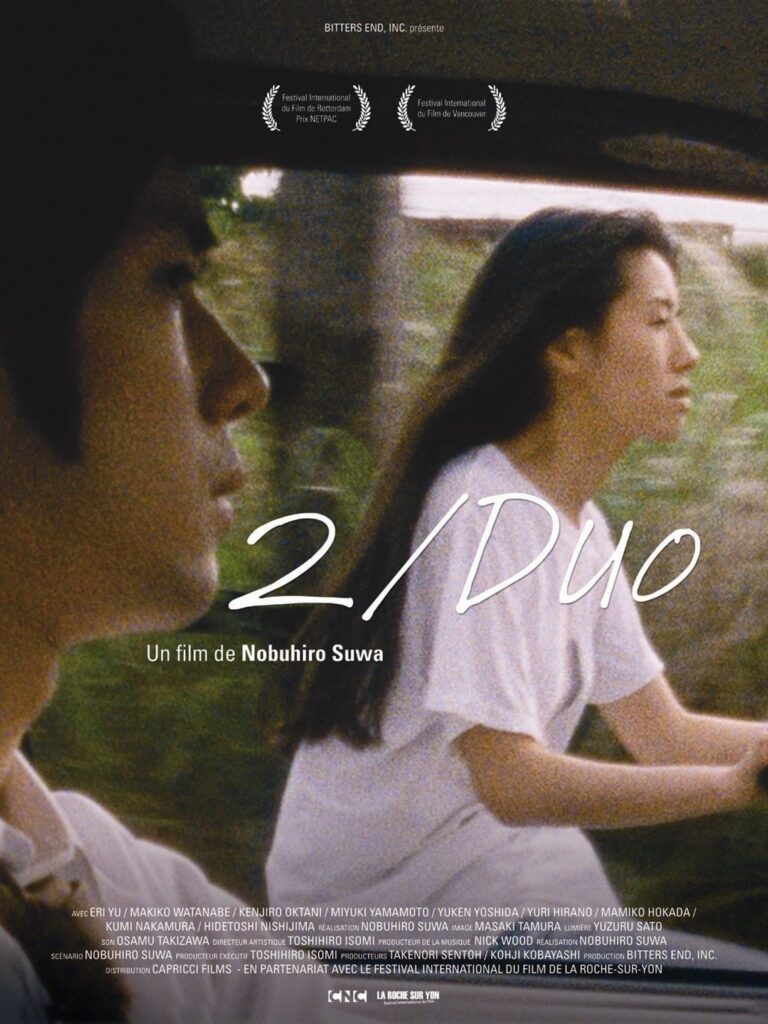

One of the most striking attributes of experimental art is the way it commonly forces us to rethink certain basics that we normally take for granted. In Nobuhiro Suwa’s 2/Duo (1996), the filmmaker’s first foray into fiction after making several TV documentaries, the vicissitudes of a young couple trying to live together — an unsuccessful actor named Kei (Hidetoshi Nishijima) and a boutique shop assistant named Yu (Eri Yu) — are so unfixed that even so seemingly simple a matter as what causes their rifts isn’t clearly spelled out. Their scenes together are vivid and sometimes violent, but seldom legible in the terms we normally accept from narrative fiction.

In an early scene, Kei suddenly proposes marriage to Yu, and she seems too startled by this suggestion to respond. In a subsequent scene, an offscreen interviewer (Is it Suwa or someone else? Does it matter?) asks her character why she didn’t respond, and she promises to ask Kei why he proposed to her. But when she finally does this, he can only shout, like a beleaguered Hamlet, “I don’t know!” Indeed, lack of certainty becomes the only certainty in much of what follows. Later, when Kei is also interviewed, his explanation of why he proposed to Yu is essentially negative — because he needed a form of self-definition that his identity as an actor wasn’t providing. This suggests a self-referential, and self-questioning, Cartesian side to Suwa’s art that helps to explain his affinity for French cinema, and the French-Japanese coproduction structures that dominate his more recent work.

The fact that both Kei and Yu disappear for a spell, without warning or explanation, only compounds our uncertainties about them. They can’t even explain themselves to themselves, much less to each other, or to us — suggesting an existential crisis that inevitably becomes extended to our own roles as spectators. (The two interviews with each character can be described as halfway houses between fiction and pseudo-documentary, ways of standing slightly outside the fiction that point to Suwa’s more theoretical side.)

Every act that is committed in relation to this couple’s shared impasse feels impulsive and desperate. Psychological mysteries ultimately become philosophical conundrums and aesthetic issues, no less fraught by being shared.

Suwa and his two actors are credited as the film’s cowriters, and even after we’re told that Suwa’s original screenplay was discarded and that the dialogue was mostly improvised by the actors, we still can’t conclude that these three were the film’s only collaborative auteurs. Masaki Tamura, the famous cinematographer, had a distinctive style of his own in such documentaries as Shinsuke Ogawa’s Narita: Heta Village (1973), about the lives of farmers protesting the construction of Japan’s biggest airport. Both that film and 2/Duo display a highly intuitive engagement with the characters, expressed most clearly in the way Tamura places and moves his camera in relation to them, neither anticipating their actions nor dogging them, but navigating the spaces they occupy with an intelligence that manages to project both empathy and a certain independence. His way of shooting an informal political discussion in Narita sometimes involves panning away from the person speaking — displaying an attentiveness to group interaction that finds responses to speech as important as the speech itself. And the placements and displacements of his camera in 2/Duo are often pivotal in elucidating the essence of a scene. What initially might seem a perverse choice of camera angle within the cramped space of Yu’s apartment (the main location) may turn out to be an unexpected but compelling definition of where documentary and dramatic truth can be found — a definition that revises conventional priorities regarding how a particular scene should be read, thereby encouraging us to reconceptualize its meaning. In short, Tamura offers us a fourth “voice” or perspective on the action, rather than a transparent window that simply grants us access to the other three auteurs.

Furthermore, documentary filmmakers who turn belatedly to fiction often carry with them an acute sense of the unknown and the unknowable that cling to human behavior, and which no amount of narrative closure and conventionally “settled” dramaturgy can shake off. This may be what’s most impressive about 2/Duo, as well as Alice Diop’s otherwise very different Saint Omer (2022) — both refuse or are unable (it hardly matters which) to give us a story so conventional that we’re able to forget it as soon as we leave the theater, which is the way most movies are expected to function. These films’ defiant lack of resolution is painfully closer to life than to art, making them a challenge to be wrestled and argued with, not swallowed whole with any expectation of immediate gratification. 2/Duo is a film that engages us with food for thought rather than characters who are easy to identify with.

What remains unsettled in 2/Duo is apparent even in its divided title, the very badge of its intransigence. It plays out its scary psychodrama from oblique angles, where every shot is more question than answer, fostering a kind of existential uncertainty personified in the actors’ frozen silences and abrupt explosions. The fact that these silences and explosions seem interactive, as if one produces the other, suggests a certain wave of social repression underlying Japanese culture in general, which the film can be said to reflect without commenting upon.

Part of Suwa’s talent is to motivate the audience to start questioning certain habits associated with mainstream moviegoing, so that our sense of real time passing can sometimes overwhelm whatever story is being told, allowing one to tune out of the fiction and into the reality of a theatrical exercise without skipping a beat. (Indeed, this is precisely where the interviews with Kei and Yu seem to figure.) The camera movements never need any excuse to hide behind a fiction, so they offer an extra perspective on the action, though not necessarily a privileged one.

When I met Suwa back in the ’90s, I asked him if he regarded John Cassavetes as an influence. His response was an emphatic and somewhat irritated “no”; it seemed that many others had asked him the same question, perhaps provoked by the popular misconception (which I sometimes shared) that Cassavetes’s films were improvised. (Shadows, Cassavetes’ 1959 debut feature, did grow out of improvisations in Cassavetes’ acting workshop, but its dialogue was mostly scripted.) But when I tentatively ventured the name of Jacques Rivette, Suwa’s eyes lit up and he nodded vigorously. And it’s true that actors writing and/or improvising their own dialogue is a basic facet of Rivette’s L’amour fou (1969), Out 1 (1971), and Celine and Julie Go Boating (1974), all of them major “workshop” enterprises where mysteries and ambiguities about the characters abound.

A sense of dread and fear around uncertainty is also a hallmark of Rivette’s most adventurous films. Whether it’s Bulle Ogier as the actress/heroine of L’amour fou or Jean-Pierre Léaud (who would later star in a subsequent Suwa film, The Lion Sleeps Tonight [2017]) as the crazed interrogator of Out 1, the emotion arising from uncertainty is a form of terror. And as Rivette declared during the mid-’60s, “The role of a work of art is to plunge people into horror. If the artist has a role, it is to confront people — and himself first of all — with this horror, this feeling that one has when one learns about the death of someone one has loved.” Even though nothing in 2/Duo seems as hopeless as Rivette’s pronouncement, it’s still a thoughtful glimpse into the abyss that can form and grow inside a relationship, all questions and no answers.