For Cineaste, Spring 2020. — J.R.

Paulo Emílio Salles Gomes

On Brazil and Global Cinema

Edited by Maite Conde and Stephanie Dennison.

Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 2018, 242 pp.,

Hardcover: $199.99, Kindle: $64.60, Paperback (from

University of Chicago Press): $68.00

Brazilian critic, film historian, and teacher Paulo Emílio Salles Gomes (1916-77) is principally known outside of Brazil as P.E. Salles Gomes, the author of the 1957 book Jean Vigo — not only a definitive biography, essential to Vigo’s posthumous rediscovery, first published in France (and translated from French to English in the early 1970s by the author), but also clearly one of the first major critical biographies of any filmmaker in any language. The editors of this volume, however, usually refer to him simply as Paulo Emílio, and picking up on their friendly Brazilian etiquette, I will follow suit.

$68.00 is an outrageous price for a paperback book less than 300 pages long, suggesting a volume intended only for well-funded libraries and professors with institutional perks to spare. But I’m also obliged to report that this first collection by a major and widely neglected figure in film studies redirects my thoughts about cinema like few other recent books. Even though its author was above all a polemicist, some of whose subjects might seem as remote and as dated as past polemical struggles from a faraway nation are likely to be — making me far more engaged with this volume’s “Social and Cinematic Engagements” (part one, 44 pages) and “Foreign Dialogues” (part two, 100 pages) than I am with “National Cinema” (part three, 77 pages) – the singularity of Paulo Emílio’s voice and his passion remains a constant.

I’m in no position to judge the editors’ selection of essays, but even for a novice on Brazilian cinema, it’s frustrating to find no discussions here of Nelson Pereira dos Santos, Carlos Diegues, or Ruy Guerra, and a 1961 discussion of Mario Peixoto’s 1931 Limite that’s basically restricted to Paulo Emílio’s complaints that he hasn’t been able to see it for twenty years and that Peixoto’s behavior has only made things worse.

It’s both tempting and inadequate — even flat-out wrong — to call Paulo Emílio the Brazilian André Bazin, despite his importance as a major father figure for Brazilian cinephiles and as a cosmopolitan intellectual with a theoretical bent. It’s true that he first became a cinephile in Paris, as a political exile in his early 20s, where he lived for a spell after escaping with others from a Brazilian prison (he’d been arrested when he was 19, for his anti-imperialist activism), and it’s also worth noting that Bazin gave his Vigo book a rave review — and that Bazin is also the focus of an excellent 1959 essay included here, written shortly after his death.

Paulo Emílio began his extensive research on Vigo in the mid-1940s, when he was attending the Paris film school l’IDHEC, where future filmmaker Pereira dos Santos was one of his classmates. But for all his Francophilia, most of Paulo Emílio’s life and career was spent in Brazil, and apart from being more of an academic and less of a journalist than Bazin, his taste for poetic hyperbole seems distinctly Brazilian and just as distinctly non-Bazinian. Here’s how he ends the last text of his included in this collection, a 1977 tribute to Glauber Rocha: “Through film, writing, speech and life Glauber has become a magical character, and to be a contemporary or compatriot of his is not easy. He is one of our strengths and we, Brazil, are one of his weaknesses.”

Or consider the following: “While intellect played a modest role in the artistic careers of D.W. Griffith and Thomas Ince, it was essential for Marcel Proust and George Bernard Shaw. Cinematographic creation has, for several decades, neglected the intellectual skill that is so indispensable to novelistic and theatrical literature. In this respect, Molière would defeat Chaplin. The unimportance of intellect explains the surprise and even deception when discovering great filmmakers, such as G.W. Pabst, Jean Renoir, Vsevolod Pudovkin, Erich von Stroheim or even René Clair. Of these, I am most familiar with Stroheim, the greatest and certainly the least intelligent of them all.” (“Unnecessary Intellect,” 1957.)

For me, the power of this passage doesn’t necessarily derive from any spot-on accuracy — even though it’s worth stressing that Paulo Emílio knew Stroheim personally. (When he organized the first international film festival in São Paulo in 1954, Stroheim and Bazin were among his guests.) I lack Paulo Emílio’s uncanny confidence in gauging the intelligence (and/or the intellectual capacity, which surely isn’t the same thing) of Chaplin, Clair, Pabst, Pudovkin, Renoir, and Stroheim, not to mention the gall to implicitly label them inferior to my own, so part of what floors me in such a declaration is its brazen audacity. In “Eisenstein’s Thinking”, written the same year, Paulo Emílio expresses no such misgivings about Eisenstein’s intellect or intelligence, and five years later, he unabashedly declares, “October is surely the richest and most complex film ever made.” Orson Welles, discussed in several essays, is granted almost comparable respect. Even though Paulo Emílio concludes at the end of a very detailed contemporary analysis that “Citizen Kane is far from a masterpiece,” he hastens to add that “It is suggestive, however, of what a great film could be.”

Yet regardless of whether his qualms about the minds of the other half-dozen filmmakers are justifiable, I can only admire his capacity to reorient my perception of them, by dividing my sense of their sensitivity and perceptiveness from their intelligence, and meanwhile forcing me to reconsider what I mean or think I mean by intelligence (theirs or mine) in the first place. In his 1965 essay “Is Chaplin Cinema?”, where he states, “I believe Chaplin is quite likely the greatest genius of the century,” he offers another version of the same reformulation by indirectly suggesting that what we call Chaplin’s intellect may be located more in his lower extremities and reflexes than in his brain; and when he writes, “Chaplin’s life seems like a fruitless and never-ending self-taught adult education course,” I find I can agree with him, but only if I substitute “fruitful” for “fruitless”.

And indeed, it’s the fruitfulness of Paulo Emílio’s suggestive prose that finally counts the most. The power of his criticism rests in its ability to interrogate and shake up what we mean (or think we mean) by talent and intellect, all in the process of exploring why so many intellectuals have distrusted cinema and so many film critics have given them ample reasons for their distrust. (At the end of his vitriolic 1941 “Against Fantasia,” he rejoices in the fact that having seen Citizen Kane just after he saw Walt Disney’s Fantasia, “the disappointment of Fantasia was not so embittering. I do not care about Fantasia any more. I want to forget Fantasia. Watching Fantasia again after having seen Citizen Kane was a sacrifice for me. I now want to see Citizen Kane many more times. I want to dive into Citizen Kane, bathe in Citizen Kane, because modern cinema is dirty.”

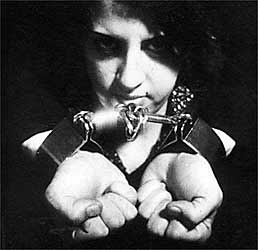

As editors Conde and Dennison helpfully point out, Paulo Emílio’s key theoretical position, which partially accounts for his reverence for October, is a demand for rhythmical unity, and finding this unity lacking in The Long Voyage Home, Citizen Kane, and Fantasia becomes the basis for his separate critiques of all three. (The sin of the latter: “The auditory musical rhythm and the visual cinematographic rhythm are two separate worlds, each with its own developmental laws and clearly defined limits,” so Disney’s willful conjoining of the two becomes an inelegant shotgun marriage.) By contrast, the separate stylizations of children and adults in Vigo’s Zéro de conduite are analyzed ideologically as well as aesthetically in a brilliant excerpt from Paulo Emílio’s biography where a certain form of calculated disunity is pointedly celebrated. –- Jonathan Rosenbaum