Commissioned by the Lima Film Festival in Peru in 2018. — J.R.

Whenever someone tells me that it’s impossible for films to change the world, I like to point out that only half a year after Luc and Jean-Pierre Dardenne’s Rosetta won the Paume d’or at the Cannes Film Festival in 1999, a new Belgian law known as “Plan Rosetta,” which prohibited employers from paying teenage workers less than the minimum wage, was passed. And one could further point out that Rosetta “changed the world” in several other ways: it launched the substantial acting career of its eponymous, 18-year-old lead actress, Émilie Dequenne, it greatly enhanced the careers of its writers-directors, and it deeply affected a good many spectators, myself included — viscerally, aesthetically, spiritually, and politically.

The visceral impact came first: From its opening seconds, Rosetta makes it clear that its heroine is angry — before it tells us who she is or what she’s angry about. Alain Marcoen’s virtuoso handheld camera, which stays close to her throughout the film, follows as she slams a door, strides through the industrial workplace where she’s just been laid off, and then assaults her boss when he insists that she leave. After taking the bus back to the trailer park where she lives with her alcoholic mother, Rosetta stops briefly in the woods and methodically takes off her shoes and puts on a pair of boots hidden behind a large rock in a drainpipe. This ritual is repeated throughout the film, marking the transition between her work and her even more solitary home life, where most of her time is spent keeping her mother away from booze and sex (her mother’s principal method of acquiring booze), fishing in a nearby muddy creek, and soothing her stomach pains, usually by warming her belly with a hair dryer.

She’s a grim character in a grim set of circumstances, yet the Dardennes are so ruthlessly unsentimental, uncynical, and physical in their approach to her life that we experience it physically before we even get a chance to reflect on its meaning. Toward the end of the film Rosetta has to carry her mother across the trailer park, and it’s extraordinary how much Marcoen’s camera style makes us feel the actual weight of the body she’s carrying.

The fact that Rosetta won the main prize at Cannes obviously helped to publicize the plight of many Belgian teenage workers, which helped in turn to increase the minimum wage for such workers. But according to the New York Times and its top film reviewer’s favorite Cannes celebrity in May 1999, Harvey Weinstein, the film was “irrelevant” and its prize only proved that the festival, by virtue of becoming political, was becoming less “serious”: “There’s something wrong with Cannes, and it needs to be fixed,” Janet Maslin quoted Weinstein as saying in her May 30 “wrap-up” piece. “The luster of the festival is completely submerged. It’s losing its place in film history. It has the potential to be so much more than it is now, the potential to be so much more serious and less political.”

More recently, Weinstein has become persona non grata at the Times, at least as a “serious” spokesperson on cinematic subjects, on account of his sexual crimes, his status as a sexual predator. But his artistic crimes — which include his suppression of such major films as Jacques Demy’s Les Demoiselles de Rochefort, Abbas Kiarostami’s Through the Olive Trees, and Jacques Tati’s Jour de fête (all three of which he acquired as a distributor and then made unavailable to most markets) and his re-editing or attempt to re-edit countless other films, including Jim Jarmusch’s Dead Man and Chen Kaige’s Temptress Moon — remain unmentioned at the Times, perhaps because they aren’t regarded as crimes at all but as legitimate forms of doing business.

For the New York Times as well as Weinstein, business is ultimately regarded as the principal raison d’être of art cinema. This isn’t so much an objective observation — although it’s often described as such, even by a few artistically oriented filmmakers such as Peter Greenaway — as it is a prescription and a directive for how both filmmakers and viewers should think and behave. After all, if the art of cinema is a disposable art, designed to be consumed and then forgotten, this means that the same films can be endlessly reseen as if for the first time, generating more income and thereby theoretically making the producers wealthier and the audience poorer.

If, on the other hand, one concedes that films are part of life and part of the world, and that they are therefore capable of affecting (i.e., changing) lives and thus changing the world, it could be argued that everyone becomes richer in such a process. Yet accepting such a premise also usually entails accepting the premise that artists, works of art, and audiences, simply by virtue of being parts of the world, are all essentially unknowable — or at the very least unpredictable — entities, not the sort of entities whose behavior can be predicted with the same amount of certainty as the weather. And as everyone knows, even predicting the weather is far from being a foolproof activity So those preoccupied with the business of cinema, who would also like to control or at least regulate the art of cinema, need to be reminded that predicting the effect of works of art on audiences can never be a science, no matter how many remakes or sequels are foisted on the public, and no matter how much control is exerted over which of these are shown in which (or how many) cinemas or turn up in which (or how many) video stores or streaming services, and which of these items the audiences hears or learns about. The most you can be sure of is that if the audience wants to see a film and you can control what its choices are, what they choose to see will be partially subject to your control and not to their own taste or preferences, regardless of what you might claim afterwards about “giving the audience what it wants”. (If an orange juice stand offers only juice flavored with soap or juice flavored with shoe polish, how much does a customer’s choice tell us about his or her tastes or preferences? Yet these are the sort of choices often inflicted on the public.)

***

Sometimes films change the world accidentally, in an unplanned and haphazard fashion. Reportedly Frank Capra’s It Happened One Night (1934) wound up almost destroying the market for men’s undershirts after males in the audience discovered that Clark Gable’s character didn’t wear them, which suggested that they didn’t need to, either. The fact that this happened during the latter stages of the Depression, when people were still preoccupied with various ways of saving money obviously contributed to such a phenomenon.

***

When it comes to charting how much and in what ways films have changed my own life and world, the first example that comes to mind is the degree to which Jacques Tati’s PlayTime (1967), one of my favorite films, taught me how to live in cities. I can be fairly specific about this. The first time I saw the film, in 1968, I was a New Yorker vacationing in Paris during the immediate aftermath of May 1968 — that is, in June 1968, arriving in Paris on the same day that the police “took back” the Odéon theater from the students, only a block away from my hotel. The film’s impact on me was more gradual than immediate, but it grew after I saw the film a second time, to the point where after I decided to move all my belongings from New York to Paris in the fall of 1969, part of the stimulus and motivation for this was an appreciation for street spectacle nurtured by Paris and trained by the compositional strategies of PlayTime, which taught me how to appreciate diverse things happening simultaneously within urban spaces in relation to one another, with my eyes and brain connecting them creatively, poetically, and sometimes comically in various ways.

Walking in New York, I had often been feeling alienated by sensory overload, which caused me to ignore things happening around me, despite the fact that the cultural riches, cinematic and otherwise, offered by large cities were too vital to my existence for me to imagine forsaking them for the beauties of the countryside, even after having spent the better part of two years at a boarding school in picturesque Vermont. The rigors of city life required an active and creative participation from me — not a simple contemplative receptivity, such as what I most often experienced in Vermont — and the Parisian pleasure of sitting in outdoor cafés, combined with the viewing tips implicitly contained within Tati’s intricate mise en scène of how best to appreciate such spectacles, encouraged me to engage in a different way with the people and movements, the sounds and images, that surrounded me. Over the next five years, it may have even improved some of my social skills in addition to my capacities as an observer and listener, in spite of a disability when it came to learning how to speak and understand French properly that I shared with all three of my brothers. (One of them was married for many years to a French woman but has never learned how to speak the language; another one lived for an extended period in Costa Rica but never learned Spanish.) Is it possible that such a disability might have been even exacerbated by the Tatiesque characteristic of privileging textures of sound and arrangements of images over linguistic distinctions?

I should add that, paradoxically, the lessons PlayTime had to teach me about processing sensory overload on sidewalks and streets largely came from a lengthy sequence that was set indoors — a sequence that actually comprises almost half of the entire film, or at the very least more than a third of the running time. It’s not even certain when this sequence actually begins — does it start with various street pedestrians watching the last-minute construction of the establishment, or does it begin more properly with the restaurant’s official opening? — but I will assume that it ends with one of the few antirealistic gags in the film, the early-morning crowing of a distant rooster, as various restaurant customers stagger out into the street.

***

Vermont, I should note, furnished only a small part of my non-urban upbringing. A much larger part came from my first sixteen years of growing up in the small town of Florence, Alabama, where my paternal grandfather owned and operated a small chain of movie theaters in Florence and three other smaller towns in northwestern Alabama (Sheffield, Tuscumbia, and Athens) — establishments where I spent a huge amount of my childhood — and my father worked for him.

From this standpoint, films (or, rather, movies, as they were called) may have composed my early environment almost as much as small-town Alabama and reformed Judaism did, and the literary efforts contained in my first book, Moving Places: A Life at the Movies (1980), were largely personal strategies for trying to reconcile and interrelate these three separate and mainly disparate cultural strands in my childhood. For this reason, a recent personal essay film by Travis Wilkerson, Did You Wonder Who Fired the Gun? (2017), concerning his own familial roots in rural Alabama — specifically, about the murder of a black man by Wilkerson’s own great-grandfather in Dothan, Alabama in 1946, when I was three years old — has a great deal to say to me.

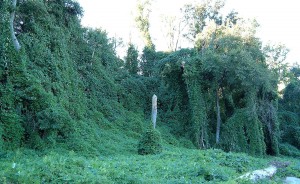

Indeed, I can’t think of any other feature that captures my home state accurately — and more beautifully, for that matter. (In terms of accuracy, the only other contender may be Phil Karlson’s 1955 The Phenix City Story, shot about a hundred miles north of Dothan.) In fact, the extraordinary beauty of Wilkerson’s photography is the most significant thing that A.O. Scott’s favorable review in the New York Times neglects, and I’m not thinking of beauty as some aesthetic “extra” but as a central part of the film’s anger and fury and eloquence and passionate attentiveness. Entanglement is what this film and this state are all about — you can call it a form of kudzu[1] made flesh — and this is arguably the very condition of the American tragedy, especially in the blighted era of Donald Trump, the ties that bind and suffocate us. You can find it equally in the twisted, curving paragraphs of William Faulkner and in the embracing swelter of the surrounding vegetation.

I should stress that Wilkerson, unlike me, is not a Southerner, and that the implicit self-interrogation of his film is more a matter of family than one of region (apart from the fact that he traveled to Alabama in order to investigate the murder and make a film about it). But the degree to which his film is conceived as an existential confrontation and self-interrogation is none the less enhanced by the way that he first presented it — as a performance piece in which his own narration is delivered “live” — at the Sundance film festival in 2017, portions of which are included on the DVD of the film released by Grasshopper Films. This already suggests, in the most direct way possible, that his investigation into the tainted past of his ancestor is not merely theoretical or hypothetical but something that is taking place in a real, present-day world that we share with him.

***

Fourteen years ago, I had occasion to test another film about the American South in relation to my own family, when I wrote about my favorite John Ford film, The Sun Shines Bright (1953), for a joint retrospective devoted to his films and Straub-Huillet’s at the Viennale.[2] For me, it’s a film that provokes a very complicated moral response by espousing a certain form of reactionary liberalism — including a patriarchal attitude about white supremacy that reflected my own grandfather’s behavior towards his black servants, as well as a supposedly firm position against lynching an innocent black youth that curiously and paradoxically also advocates a “politically correct” form of lynching when it wholeheartedly approves the shooting of a guilty white rapist who is attempting to flee — a murder committed by a hillbilly played by John Ford’s older brother, Francis Ford, which the film’s patriarchal hero, Judge Priest (Charles Winninger), fully endorses (“Good shootin’, comrade”), because it saves everyone the trouble of holding a trial. This is a film, in short, that fully reflects the same contradictory humanism as the society it’s concerned with, which leads one to the question of whether accurately reflecting a society can function as a prerequisite for changing it or if it functions instead, finally, as a glib form of acceptance, as a substitute for changing it.

This is a question also posed implicitly by Carl Dreyer’s last feature, Gertrud (1964) — another favorite film of mine, and one that I’ve often associated with The Sun Shines Bright. In the case of Dreyer’s film, we have a tragedy tha juxtaposes the title heroine — a woman who can exist only in the present and is incapable of growth or change, rather like Judge Priest in Ford’s film — with three men who become romantically involved with her at separate stages and in different ways, all of whom fail to live up to her ideals and expectations.

Psychoanalytically speaking, Gertrud becomes identified with two forms of stasis and nonnarrative — namely prebirth and death — while the men who fail her, all of whom have to cope with pasts and futures, are all condemned to live and struggle in the world, that is, between birth and death. The impossibility of Gertrud occupying the same world as these men is what makes the story a tragedy.[3]

***

Gertrud was poorly received when it was first released in the mid-1960s, largely because audiences found it difficult to reconcile the film’s period setting — most of it is set in 1906—with the present. Although Gertrud might be regarded as the most “modern” of Dreyer’s features in terms of its radical form, the fact that most of its action is set over half a century earlier led many viewers to see it as old-fashioned and even archaic. And it would appear that a similar problem exists with the recent posthumous completion and release of Orson Welles’ The Other Side of the Wind — set in the present but shot in the early 70s, which means that most of its action occurs almost half a century ago. In the case of the Welles film, the ideological ramifications of this time lapse are even more pronounced, especially in relation to various codes of etiquette involving both gender and race, which have changed substantially. The same sort of problem existed with This is Orson Welles — an interview book prepared by Welles and Peter Bogdanovich over roughly the same period that I was hired to edit in the late 1980s and early 1990s. For instance, it was perfectly normal and acceptable for Welles to use the term “Negro” in 1969 or 1970, but Bogdanovich insisted on changing this term to “black” two decades later to match contemporary standards and biases, even though this falsified the record historically. Similarly, what might have been regarded as an acceptable “liberal” or “progressive” practice in 1969 or 1970 —such as Oja Kodar, a Croatian, dying her skin red to play a Native American — has become “politically incorrect” in 2018 due to identity politics, and even the film’s attack on macho behavior which arguably would have qualified as feminist in the 70s has been read today by some viewers as misogynist.

One also has to consider how films are publicized and how they are defined by reviewers in order to help determine their probable social impact. The Other Side of the Wind has been incorrectly labeled “Orson Welles’ last film” by Netflix, which has also tended to emphasize the film in its publicity as a satire about Hollywood while downplaying its more ambiguous critical treatment of gender and sex roles and often minimizing the creative role played by Welles’ partner Oja Kodar as screenwriter, who (for instance) thought up the film’s title and was the one who decided to make her own character a Native American. But it’s also worth emphasizing that test-marketing and advertising both privilege immediate responses over delayed or long-term reactions, so that simpler definitions of a film are preferred to more complicated or ambiguous ones (which is why Netflix prefers to call The Other Side of the Wind a “satire of Hollywood” than a critique of macho behavior or attitudes), and previews are designed to test only an audience’s first responses to a film, not what they might think or feel an hour or a day or a week later.

One also has to consider that what makes a film “political” in its own period might — or might not — make it political in a contrary fashion a few decades later because fashions and standards of judgment are always subject to change. When Jake Hannaford (John Huston), the aging macho filmmaker in The Other Side of the Wind, jokingly calls his leading lady (Kodar), a Native American, “Pocahontas”, this racial stereotype might be said to coincide precisely with the jeering racism of Donald Trump when he assigned the same nickname to the U.S. Senator Elizabeth Warren after she claimed to have a Native American ancestry. Yet at the same time, Kodar’s decision to play a Native American in the film doesn’t mean precisely the same thing today that it meant in 1969 — or might have meant, if the film had been completed and released in the same era.

***

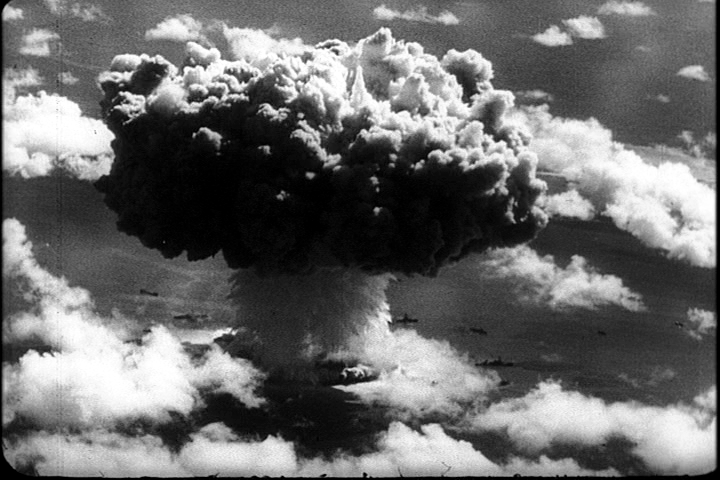

Although I have no way of proving this, I strongly suspect that the enthusiasm of much of the American public for both the Gulf War of 1991-1992 and, at least initially, for the so-called Iraq War of 2003 can be attributed in part to the popularity of Star Wars and its sequels, which sold the American public on the notion of “war” (or, more precisely and accurately, violent military occupation) as an essentially bloodless video game to be enjoyed by families and households as an abstract spectacle for non-participants.

Similarly, when it came to selling the American public on the invasion of Iraq as a valid and “just” response to destruction of the Twin Towers on September 11, 2001, I think it’s even likelier that the countless Hollywood movies encompassing as well as promoting elaborate fantasies of revenge — perhaps most blatantly in the films both emulated and made by Quintin Tarantino, but also in such respected and prestigious movies as Taxi Driver, the Godfather trilogy, and numerous other gangster sagas — all played a significant preparatory role. Collectively, they firmly established the notion that some sort of counter-violence was a psychic necessity, while the issue of whom the recipients of this violence might be was secondary, almost an afterthought.

***

Having just seen Henry King’s 1958 CinemaScope Western The Bravados — possibly for the first time, on a Blu-Ray — I’m especially struck by how much the executive machinery at 20th Century-Fox, in particular its publicity machinery, still largely determines the film’s social meaning and social impact, sixty years after the film’s initial release. In 1950, another Western directed by King for the same studio, also starring Gregory Peck, was released, called The Gunfighter. It qualified as a revisionist Western in many respects because it sought to criticize and deconstruct the myth of the gunfighter who is known to be “the fastest gun alive,” revealing that myth to be a ridiculous burden for the gunfighter to live with or to die from more than any sort of enviable honor. In short, the film was a conscious effort to counter certain aspects of Western mythology with a realistic approach, including even a tragic ending, as well as the stylization of Gregory Peck’s handlebar moustache. According to Wikipedia’s entry on the film, “The studio hated Peck’s authentic period moustache. In fact, the head of production at Fox, Spyros P. Skouras, was out of town when production began. By the time he got back, so much of the film had been shot that it was too late to order Peck to shave it off and re-shoot. After the film did not do well at the box office, Skouras ran into Peck and he reportedly said, ‘That moustache cost us millions’.”

Eight years later, Henry King made another revisionist Western with Gregory Peck, this time seeking to undermine both the alleged justice and the dramaturgical satisfactions of the standard revenge plot, in which Peck’s character, a rancher, joins a group of townspeople chasing a gang of four bank robbers, believing that they’re the same gang who raped and killed his wife. But after personally killing three members of this gang, he belatedly discovers that these men weren’t the gang who raped and killed his wife — a discovery comparable to that of many Americans who realized belatedly that Saddam Hussein in Iraq didn’t have any “weapons of mass destruction” and wasn’t responsible for the September 11 attacks. After Peck guiltily confesses his fatal error to a priest, he’s told that at least he feels some remorse about what he’s done, unlike others who would claim that the men deserved to be killed anyway. And immediately after this scene, Peck’s character is cheered by all the townspeople as an authentic hero and the movie ends happily on this note, thereby allowing the irony of this celebration to be minimized or overlooked for the sake of a conventional upbeat ending. Furthermore, if one looks at some of the extras on the Blu-Ray of The Bravados, such as the trailer and even an item called a “Quick Draw Lesson by Hugh O’Brian,” or the accompanying essay that describes the film as “gloriously grim” (the glory in this case plainly coming from the revenge more than the guilt), it immediately becomes apparent that the standard endorsement of revenge and violence predominates in this presentation, without much of the skepticism or irony about their mythology that King or his screenwriter, Philip Yordan, might have intended.

We might also speculate how much the implicit celebration of remorseless killing by a serial killer in The Silence of the Lambs amounted to an implicit support of the then-ongoing Gulf War in 1991, and how much the enjoyment of remorseless killing by another serial killer in No Country for Old Men amounted to a support of the military occupation of Iraq in 2007. To ask such a question, of course, isn’t the same thing as claiming to answer it. Yet to accept the immense popularity of these two films without any qualms or doubts, as most reviewers have done, as if they had no social or political significance at all, strikes me as being willfully naïve — and perhaps also usefully naïve, I might add, from the vantage point of these films’ producers, distributors, exhibitors, and publicists.

Here’s a portion of my remarks on this subject in the Chicago Reader:

“One reason I tend to dislike movies about psycho killers is that I can’t respond to them with the devotion I feel is expected of me. I’m too distracted by the abundance of these characters on-screen when they rarely appear in real life, and by how popular they seem to become whenever we’re fighting a war. What is it about them that people find so exciting? Reviewing The Silence of the Lambs over 16 years ago, I was troubled by the way the thriller tapped into ‘irrational, mythical impulses that ultimately seem more theological than psychological,’ and how critics who loved it seemed ‘better equipped to regurgitate the myth than to analyze it.’

“I was especially bemused by the ready acceptance of Hannibal Lecter’s supernatural powers — his ability to convince a hostile prisoner in an adjoining cell to swallow his own tongue, for instance, or to know precisely when and where to reach Clarice, the movie’s heroine, on the phone. Anthony Hopkins’s Oscar-winning performance may be stark and commanding, but it wouldn’t have counted for beans if the audience hadn’t already been predisposed to accept this murderer as some sort of divine presence.

“The waves of love that went out to Lecter, epitomized by the five top Oscars the movie received in 1992, were a mix of giggly fascination, twisted affection, and outright awe for his absolute lack of remorse. This was during the first Gulf War, a time when we were grappling with our own feelings about killing masses of people on a daily basis. I suspect Lecter represented a savior of sorts, a saintlike holy psycho who made us feel less uneasy about wanton slaughter [….]

“The picture of human nature in No Country for Old Men is…so bleak I wonder if it must provide for some a reassuring explanation for our defeatism and apathy in the face of atrocity….As I left the screening in Toronto, all I could think was, ‘America sure loves its mass murderers.’ That conclusion was ratified by a line in the New York Film Festival’s blurb for the movie: ‘Wearing an unforgettably frightening pageboy and toting a cattle stun gun that’ll haunt your nightmares, Javier Bardem is Anton Chigurh, a psychopathic assassin of the highest order whose detachment is as shocking as the carnage photographed so gorgeously by DP Roger Deakins.’ […]

“This grisly thriller qualifies in some ways as a remake of the Coens’ Fargo, with Bell and Moss jointly taking over the role of Frances McDormand’s pregnant sheriff. Bell is the film’s moral center, the law in the midst of greed and senseless death. Moss, already marked by his relative indifference to the suffering of a dying Mexican in the opening sequence, becomes lovable only during his affectionate banter with his wife, Carla Jean (Kelly Macdonald). He’s the character we’re supposed to identify with, especially when he’s trying to match wits with the psycho killer. […]

“There’s a certain cleverness in the way the Coens, after piling on the corpses in the opening sequences, elide some of Chigurh’s actual murders toward the end, flattering the audience by suggesting they’re sophisticated enough to imagine the ‘gorgeous carnage’ all by themselves. They even manage to acknowledge briefly the relevance of all this mayhem to the present occupation of Iraq (albeit somewhat anachronistically, as the action is set in 1980). At one point, Bell ruefully reflects to a colleague, ‘It’s just all-out war — there isn’t any other word for it,’ and goes on to comment about the sad times we’re living in, when some people even resort to senseless torture, making particular allusion to Abu Ghraib by mentioning a torturer placing a dog collar around the neck of one of his victims.

“But just because the Coens are hip enough to know the contemporary audience they’re addressing doesn’t mean they have anything to say we don’t already know, about Abu Ghraib or anything else. What I suspect they’re really offering us is a convenient cop-out: we can allow dog collars to be used even while we hypocritically shake our heads at the sadness of it all.”4

All this suggests that any comprehensive account of how a film might change the world — or, alternately (and far more commonly, alas), leave it unchanged and unchallenged) — has to take into account not only what the film itself says and does but what the surrounding culture says and does to inflect or even in some cases determine its social meanings. From this point of view, we might also ask, for instance, how much Stanley Kubrick’s sarcastically titled Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb did in 1964 to alter the arms race between the United States and Russia and how much it ultimately supported a cynical and nihilistic acceptance of this situation — that is, how much it may have actually encouraged some viewers to stop worrying and love the bomb.

End Notes

- From an online dictionary, kudzu is “a quick-growing eastern Asian climbing plant with reddish-purple flowers, used as a fodder crop and for erosion control. It has become a pest in the southeastern US.”

- Die Früchte des Zorns und der Zärtlichkeit, Viennale, 2004. The original English text can be accessed at www.jonathanrosenbaum.net/2018/08/the-doddering-relics-of-a-lost-cause-john-fords-the-sun-shines-bright/

- “Gertrud as Nonnarrative: The Desire for the Image,” Sight and Sound, Winter 1985/86 and www.jonathanrosenbaum.net/2017/08/gertrud-as-nonnarrative-the-desire-for-the-image/

- Chicago Reader, November 4, 2007, and https://www.jonathanrosenbaum.net/2007/11/all-the-pretty-carnage/