Written for the Il Cinema Ritrovato catalogue for June 2018, although they wound up not using this entry because the film got canceled. — J.R.

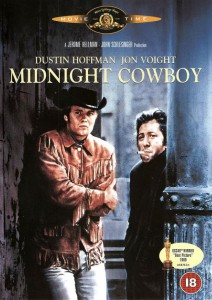

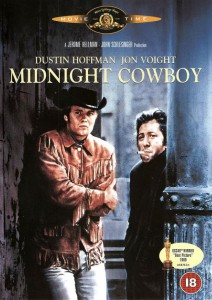

An expert piece of machinery highlighting two gifted actors — Jon Voight in his screen debut and Dustin Hoffman in the immediate aftermath of The Graduate, playing an antithetical role as a crippled street rodent named “Ratso” — Midnight Cowboy actually looks better to me now than it did in 1969. Even back then, I was impressed by the jubilant energy of the film’s opening: our introduction to Voight’s Joe Buck, the title hero, to the strains of Nilsson’s “Everybody’s Talkin’” was every bit as galvanizing as our first look at John Travolta’s Tony Manero would be eight years later in Saturday Night Fever, strutting to his own music. And much of what followed, after this Texan dishwasher boarded a bus for New York with dreams of becoming a first-class gigolo, impressed me with its deft storytelling and its eye for flavorsome detail. But English director John Schlesinger, in spite of his skill with actors, was designated as a bad object by Anglo-American auteurists such as myself — crassly derivative of the French New Wave in his flashy effects and a tireless trend-monger. Read more

The following is a chapter from my book Film: The Front Line 1983 (Denver, CO: Arden Press) — which I’m sorry to say is only available now at ridiculously inflated prices (one copy at Amazon currently sells for $989.90). It probably remains the least well known of my books. I’m immensely grateful to Jed Rapfogel and Stephanie Gray at New York’s Anthology Film Archives for furnishing me with a document file of this essay so that I could post it here, originally to help promote their Mark Rappaport retrospective in March 2011, prior to the updated version of this held earlier this year. Readers should also consult my separate articles about Rappaport’s Rock Hudson’s Home Movies and From the Journals of Jean Seberg as well as my interview with Rappaport about the latter, all of which are also available on this site, along with a more recent piece about two of his videos. — J.R.

When the critic of a narrative film is feeling desperate, the first place that he or she is likely to turn to is a plot summary. Feeling rather desperate about my capacity to do justice to the last two features of the remarkable Mark Rappaport, I looked up the synopses and reviews of The Scenic Route and Impostors in the usually reliable Monthly Film Bulletin, which appeared precisely three years apart (February 1979 and February 1982), only to discover that each critic, Geoffrey Nowell-Smith and Simon Field, respectively, starts off with the admission that his own synopsis is misleading. Read more

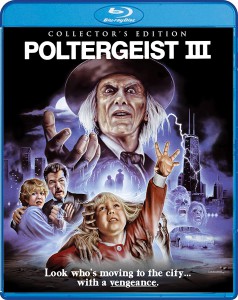

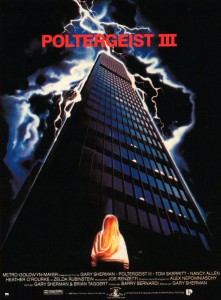

From the Chicago Reader (June 1, 1988). — J.R.

In this strictly routine second sequel to Poltergeist, directed by Gary Sherman from a script by Sherman and Brian Taggert, Carol Anne (Heather O’Rourke) is now happily living in Chicago with her uncle Bruce (Tom Skerritt), aunt Pat (Nancy Allen), and cousin Donna (Lara Flynn Boyle). But during a session at school with a therapist (Richard Fire) something nasty starts to happen when she looks in a mirror. Most of the action is confined to a single brand-new skyscraper, and the moves are both standard and predictable: periodic jolts from the other world that seem almost arbitrarily spliced into the action, setting up the rational-minded therapist as the major fall guy, and never paying much mind to plot or coherence, meanwhile cribbing from everything in sight (The Exorcist, The Shining, the first two Poltergeists). (JR)

Read more

Read more