From the Chicago Reader (January 9, 1998). — J.R.

Do movies come from the tooth fairy? When you consider the way that they’re often treated in this culture — in particular, what films are made available and are therefore considered “important” — the working hypothesis appears to be that movies magically appear and disappear. The general idea is that the designated tooth fairies of product flow — producers, directors, distributors, exhibitors, and critics — make things happen and the only thing viewers are supposed to do is show up for the movie, rent the video, or decide to do neither.

Most viewers understandably don’t want to be bothered with the machinations that determine which movies turn up and which don’t. To tell the truth, most critics don’t want to be bothered with these matters either. But sustaining such innocence may involve too high a price. Readers who complain that 1997 was a mediocre year for movies are probably counting only the multiplex entries, only one of which made it onto my ten-best list — though why anyone would eliminate everything else in a city like Chicago remains a mystery, perhaps explainable by saturation advertising, mass-media complicity in making everything but multiplex movies look unimportant, and the supposed inconvenient locations of some theaters.

Looking to me for movies worth renting on video entails setting fairly low horizons: not only because seeing most movies on video won’t do them justice but also because few of the ones that will show up on video are as good as my favorites, and few even come up to the level of my honorable mentions. But for the video-bound, let me give you a third-rate list right now so I can move on to more serious matters. In rough order of preference, here are my top 25, at least of those I can still remember: Mother, Lost Highway, Men in Black, Crash, Kiss or Kill, Telling Lies in America, Ulee’s Gold, Hard Eight, Boogie Nights, Jackie Brown, Titanic, SubUrbia, She’s So Lovely, Rough Magic, Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil, Amistad, Contact (for all its unevenness), Romy and Michele’s High School Reunion, That Old Feeling, Out to Sea, Hoodlum, Liar Liar, Starship Troopers, Kull the Conqueror (a bad movie, true, but a glorious one), and Austin Powers: International Man of Mystery. Some of these aren’t available on video yet, but they’re all bound to turn up eventually. And if you think my polishing off this list so cursorily is a bit flippant — though I have to say I saw nearly half of these movies twice — think how I must feel about how cavalierly most of you missed seeing the majority of my own favorites even once.

One woman who recently rang my office wanted to know if the fact that a film was reviewed in the Reader meant that it was available on video. Not surprisingly, she came across Reader reviews on the Internet: I suspect that it’s only within the vast playpen of cyberspace that such confusion could take root. In this zone, history, causality, and agency are often only dimly defined: this same woman was under the impression that I was Dave Kehr, my predecessor at the Reader who departed a dozen years ago. I also periodically get E-mail queries about the availability on video of films I reviewed eight, nine, or ten years ago, which I generally don’t answer because the questioner’s guess is as good as mine. Video rental stores are the logical places to ask instead.

One reason I’m feeling disgruntled is that I’ve been trying to figure out some way of squaring my serious list of ten favorites with something resembling market availability, and the hard truth is that, for about half of them, I can’t. Every year it seems that the rules regulating such lists, for critics as well as readers, become a little more arcane and difficult. If one attends film festivals, or even sees films outside Chicago, then it stands to reason that any regionally based list can’t be drawn from all the films one has seen in a given year. And because Chicago moviegoers are often treated like second-class citizens when it comes to some features, which are released much earlier in New York and Los Angeles, Chicago-based ten-best lists can look somewhat out-of-date in a national context. The Chicago Film Critics Association recently responded to this problem by changing its bylaws so that films shown to the press in 1997, even if they don’t open in Chicago until 1998, now qualify for the CFCA’s 1997 awards.

This change in the bylaws is one of the reasons I’m a reluctant member of the organization. Another, more basic reason is that I’m far from convinced that the collective wisdom of the CFCA is necessarily superior to the collective wisdom of the Chicago filmgoing public — the only consideration that might make the CFCA awards useful. After all, hundreds of ordinary viewers but few if any other local critics saw my two favorite films of the past year. Maybe those hundreds of people and I are wrong and the multiplex mavens are right, but don’t count on the tooth fairies to bring out any of my favorites on video and settle the issue. The truth of the matter is that no one knows everything that’s going on in cinema at any particular moment, tooth fairies included, and those who decide to pitch their tents in the multiplexes usually don’t care to know about any other films anyway.

Some in the CFCA have argued that Chicago critics in the multiplex vein are made to look stupid by national release patterns, and the new bylaws are meant to counter that impression: one might call it a Tooth Fairy Initiative undertaken by the weaker tooth fairies (the critics) in deference to the stronger tooth fairies (the distributors and exhibitors), who refuse to budge, and in further deference to the public at large, who are expected to know nothing and have blind faith in the tooth fairies’ collective beneficence. (Close your eyes, make a wish, and when you open them, the movie will be available — unless it isn’t.)

For me, these new bylaws convey to viewers the unfortunate suggestion of one-upmanship, since Chicago critics can now select the best 1997 films from a pool that includes movies ordinary filmgoers in Chicago couldn’t see in 1997 — and in some cases still can’t see. Even worse, this initiative plays directly into the hands of distributors, who hustle ad copy out of reviewers by screening some movies weeks or months in advance — furthering a process, I would argue, that makes everyone, ordinary viewers and critics alike, look and feel stupid. I can sympathize with colleagues who don’t want to appear stupid to their readers, but I can’t see how covering for the biases of distributors and/or exhibitors — the tooth fairies who are, after all, responsible for this state of affairs — can also be interpreted as a better situation for viewers, educating them about what they should see and why. (Sometimes, I might add, this recalcitrance is a blessing in disguise; so far, for example, we’ve been spared Gummo, the worst film I saw anywhere in 1997.)

End-of-the-year press shows and openings are problematic to begin with, tied as they are in many cases to eligibility for Oscars and critics’ prizes — which translate into advertising. Often predicated on big companies’ strong-arm capacity, such openings are intended to exploit the amnesia or ignorance of viewers, who might conclude that Amistad is a more profound depiction of slavery than last year’s Nightjohn or the 1975 Mandingo. (Given my antipathy to the skillful but gloating L.A. Confidential, which just swept the National Society of Film Critics and New York Critics Circle awards, I haven’t yet made time for a close second look, but it strikes me as a considerably less imaginative reworking of noir conventions than Lost Highway or Kiss or Kill.) For critics eager to get their names in ads, screenings far in advance of release are an irresistible temptation to forsake common sense and dive into the cascading hype. And from the looks of things, the new CFCA bylaws, far from seeking to alleviate this obnoxious situation, are designed mainly to facilitate it.

All this helps to explain why, despite my admiration for Martin Scorsese’s Kundun and Robert Duvall’s The Apostle — and, to a much lesser extent, for Wag the Dog — I can’t with a clear conscience recommend them as three of the best movies of 1997 just because I saw them last year. Similarly, I can’t include Abbas Kiarostami’s Taste of Cherry — a film I like even more than these, which I saw last year in Cannes and at the New York Film Festival — because the Music Box won’t get around to showing it until this spring. And I can’t include the sublime full-color 1995 restoration of Jacques Tati’s Jour de fête, playing for a limited run at the Music Box next week — technically a 1997 release because Miramax dumped it at New York’s Film Forum last fall. The restored Jour de fête, never before shown in the United States, isn’t even among the 21 “1997 Miramax releases” sent to critics, and has been dutifully ignored as a consequence.

If this means that I’m considered a back number a year from now, when I select any or all of these four films for my next ten-best list, then I’m afraid it can’t be helped. Even if art isn’t eternal, I’d like to imagine it’s enduring.

My two favorite films from last year — both of which showed two times apiece in 1997 to substantial crowds at the Film Center — are cases in point. The first, A Brighter Summer Day, was made in 1991 but was first shown here only last year. (It’s come out on laser disc too, subtitled in English, and I’m told it can be ordered from the more specialized outlets.) The second, The House Is Black, was made in 1962 and is so scarce that no print exists in North America and no still from it can be found to illustrate this article [in 1998] — though neither fact has anything to do with the film’s merit or importance.

1. A Brighter Summer Day. About a week before it showed in the Film Center’s Edward Yang retrospective in November, I described this 230-minute Taiwanese feature as the richest novelistic movie made by anyone during the 90s. And it’s only grown in resonance for me since that showing. Set during a single school year, 1960 to 1961, at a downtown Taipei high school, it boasts more firmly drawn characters than any other feature of the 90s that I can think of. Most of them are teenage boys, but there’s also a teenage girl named Ming, loved by at least two of the boys, and a couple of parents. (The film has a nocturnal lyricism that recalls Rebel Without a Cause.) Also among the “characters” are a samurai sword, an old radio, a tape recorder, an Elvis Presley song, and a stolen flashlight, all of which accrue a remarkable number of meanings and emotions as the epic plot unfolds.

Yang, who was in town for the tail end of his retrospective, told me that the school in the film is the one he attended as a teenager and that most of the incidents really happened to him and his classmates. A statement about Yang’s generation that took him four years to conceive, prepare, and shoot, A Brighter Summer Day is arguably the greatest of all Taiwanese films — surpassing even the works of a master like Hou Hsiao-hsien — because it gives a voice to a quotidian culture without a voice of its own. Moreover, it’s a voice in which exquisitely composed sounds and decanted images work in tandem — a voice that conjures up a vivid night poetry lit by little oases of illumination that endures in the mind like few other film experiences.

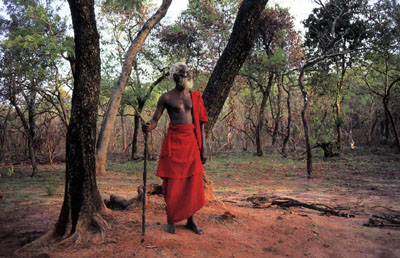

2. The House Is Black. I mainly have to take it on faith that Forugh Farrokhzad (1935-’87) is the greatest Iranian poet of the 20th century. My involvement with her only film goes much deeper: after seeing this 22-minute 1962 documentary about a leper colony a few years ago at the Locarno film festival, I resolved as a member of the New York film festival’s selection committee to get it screened there, and finally succeeded last year after agreeing to subtitle it in collaboration with several Iranians. After premiering in New York, the subtitled print showed at the Film Center twice in early October on its way back to the Swiss Cinematheque.

Thanks to my work on the film, I had plenty of opportunity to experience the overwhelming poetry of Farrokhzad’s sounds and images — including the extraordinary sound of her voice and the no less remarkable configurations of her words in relation to her sounds and images — even if I could only appreciate the power of her written poetry secondhand. But if the greatness of some films can be measured by how much they change one’s view of the world, few have altered mine as much as this precious work.

Perhaps the most formative film I saw as a child was Tod Browning’s Freaks (1932): its view of deformity, which combines compassion and horror, has been definitive for most of my life. But The House Is Black, whose radical and poetic compassion for lepers eschews any sense of horror or voyeurism or sentimentality, changed all that. Whether this vision is specifically Iranian is a question I’m not equipped to answer. It’s worth noting that when the film was made, its reception in Iran was far from unanimously positive; given its subject matter, I doubt it could comfortably enter the mainstream anywhere on earth. On the other hand, I suspect that part of my attraction to Iranian and Taiwanese films stems from their resistance to Western values, which implies they have a great deal to teach me. An Iranian friend who loves The House Is Black as much as I do told me that she didn’t much care for Yang’s Taipei Story because it reminded her too much of various Iranian films that inveighed against westernization — which implies in turn that national characteristics are merely one of the many lenses we look through when we watch movies. With or without its Iranian character, The House Is Black remains the most successful fusion of cinema and poetry that I know. I suspect this is true less for formal reasons than because of Farrokhzad’s irreducible sureness in what she has to say.

3. Irma Vep. In contrast to Yang’s film, set in the 60s, and Farrokhzad’s film, made in the 60s, Olivier Assayas’s first comedy, made in 1996, is overwhelmingly about the 90s — though its heroine (Maggie Cheung playing herself) is seen arriving in Paris to star in the remake of a French movie made in 1916. “Irma Vep” is an anagram for “vampire,” and the film she’s supposedly remaking is Les vampires, a serial about a gang of thieves dressed in black rather than a group of bloodsuckers. But the predators on whom Assayas focuses — all working on the film or in the twilight zone of the production’s fringes — are vampires in every sense of the word, nocturnal animals feeding on human flesh. A nervous movie about nervous people encircling a placid goddess (Cheung), this is an edgy comedy about alienated labor, thwarted sexual energy, and the delirious dream states unleashed by frenetic activity on-screen and off. In short, it’s a film about the way we live. (Among the other actors, Nathalie Richard and Jean-Pierre Léaud are especially memorable.)

4. The Ceremony. The strongest film in over a quarter of a century by French New Wave filmmaker Claude Chabrol, adapted from Ruth Rendell’s A Judgment in Stone, this ambiguous, powerfully acted melodrama returns to the bourgeois terrain of most of Chabrol’s best work. The mixture of love and hatred he’s always felt toward his own class resurfaces here but in a different configuration, because this time he regards his bourgeois characters with clear affection. Yet he also seems to understand the unbridled class hatred felt by a maid (Sandrine Bonnaire) and her best friend (Isabelle Huppert) toward them, and he charts it with dispassionate precision. A psychoanalyst, Caroline Eliacheff, collaborated with Chabrol on the script, but part of the picture’s uncommon impact is its capacity to carry conviction in its shocking story line without wearing its psychology on its sleeve. In this respect and others, The Ceremony shows the enduring influence of Fritz Lang on Chabrol’s filmmaking –a t least as pertinent as the influence of Alfred Hitchcock, though it’s noticed less often.

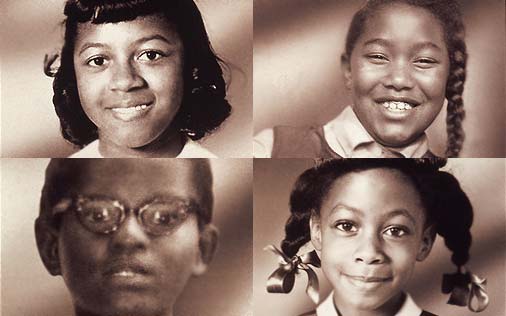

5. This one’s a tie between Spike Lee’s 4 Little Girls and Errol Morris’s Fast, Cheap & Out of Control, two radically different examples of nonfiction filmmaking. The first is a piece of investigative reporting into the lives of four black girls killed by a racist bombing at the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, on September 15, 1963. A rare act of humility, feeling, and historical nuance by a talented if uneven filmmaker who’s been gradually working his way back into the independent sector, this is for me Lee’s best effort since Do the Right Thing — and another sign, along with Get on the Bus, that he’s finally returning to what he does best, forsaking the dubious rewards of jive like Malcolm X. Morris’s Fast, Cheap & Out of Control is a highly original work that begins by interviewing four people — a lion tamer, a topiary gardener, a mole-rat specialist, and a robot scientist — and ends up constructing an evocative piece of dream poetry out of their lives, memories, and discourses.

As impressive as these two films are, if I were selecting the best documentary I saw all year, I’d have to pick Frederick Wiseman’s Chicago-made Public Housing — a more-than-three-hour dissection of what it’s like to live locally in a concentration camp. Perhaps Wiseman’s finest feature to date, this remarkable achievement deserves to be seen on a big screen — as I saw it when serving on the New York Film Festival’s selection committee. But so far it’s been shown in Chicago only on public television, which makes it ineligible for this list. A stark portrayal of what we do to some of our citizens, Public Housing is not as polemical or didactic as my brief description implies, but it furnishes us with enough material to rethink in a number of invaluable ways all the issues it raises. I hope its two recent TV airings won’t represent the sum of its local exposure.

6. La promesse. A low-budget Belgian feature by the previously unknown Dardenne brothers, Luc and Jean-Pierre, this stirring drama about the interactions between a local boy in Lige (a city in French-speaking western Belgium) and a widow from Burkina Faso with a baby son is a good example of the strength of regional filmmaking; its kind of achievements are commonly overlooked when awards get handed out. (Ulee’s Gold, by the irreplaceable Victor Nuñez, is another, though that film has the commercial advantage of a star, Peter Fonda, and as a consequence is getting more recognition.) Like Public Housing, this film is a good example of intelligent leftist filmmaking, more concerned with making discoveries than with simply propounding what the filmmakers know or think.

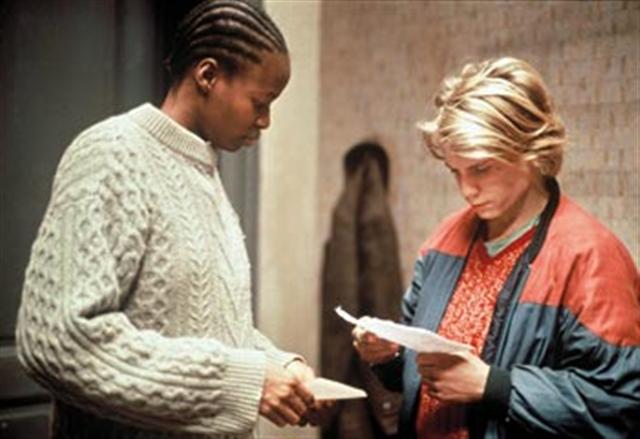

7. In the Company of Men. My favorite American independent fiction feature of the year, the first film of American playwright Neil LaBute is a bracing act of provocation, at least in a country that generally examines capitalism — which is, after all, a working philosophy affecting people’s values, behavior, and sexuality –less closely than it does the social and physical ramifications of smoking. This makes it another fine example of regional filmmaking, if the United States can be regarded as a region, and one that has a particular resonance because of LaBute’s acute sense of structure and his purposeful work with actors. Working in a minimalist contemporary American setting with a Restoration-style comic villain (Aaron Eckhart)–a bitter junior executive who’s in some ways more a force of nature than a character in the usual sense — LaBute offers each viewer the uncomfortable challenge of deciding where he or she belongs in relation to the story’s power struggles. And he coaxes highly suggestive performances from his two other leads, Matt Malloy and Stacy Edwards, both of whom play characters in the fullest sense of the word.

8. The Sweet Hereafter. Atom Egoyan flexes his muscles in this ingenious adaptation of Russell Banks’s beautiful novel about the effects of a school bus accident on a small town, effects exacerbated when a big-city lawyer (Ian Holm) turns up and tries to initiate litigation. Though the results are finally less accomplished than in the fully rounded Egoyan features Calendar and Exotica, his mastery of sound and image remains secure; the Brueghel-like long shot depicting the bus accident itself, a rare example of morphing used to artistic effect, is my favorite shot in any movie released this year. And Egoyan’s commentary on capitalism is every bit as suggestive as LaBute’s, though it’s less explicit and is complicated by the lawyer’s own tragedy, involving a wayward daughter. Few filmmakers have attempted to deal with family grief as fully and as seriously as Egoyan has throughout most of his career. And if he characteristically articulates this concern by restructuring Banks’s story, which depends on individual voices, into a set of interlocking and obsessive loops — the same structure found in most of the novels of Kurt Vonnegut — he gives the resulting drama a remarkable narrative fluency.

9. As Good as It Gets. The only purebred Hollywood item on my list — run through the industry wringer of test-marketing and other brands of second-guessing — still triumphs thanks to the volatile performances that director-cowriter James L. Brooks wrests from his two leads, Jack Nicholson and Helen Hunt, as well as more conventional but still credible work from Greg Kinnear and a dog named Jill. Brooks’s three central characters — an obsessive-compulsive novelist, a single mother with an asthmatic son, and a gay painter estranged from his parents — hover on the edge of catastrophe for most of the film, and the vitality and reality he finds in their inner struggles and their efforts to relate to one another make this the most pungent comedy-drama Brooks has turned out to date. It remains frustrating that he seems born to create musicals — I’ll Do Anything was a musical until preview audiences persuaded him to delete all the musical numbers — when our era supposedly deems explosions more entertaining than singing and dancing. Still, the spirit of song and dance presides over Brooks’s films — which reveal a poetic grasp of human interaction and his unique comic perceptions of neurosis — creating explosions in the heart and mind, and his fourth feature gains immeasurably from this energy.

10. Comrades, Almost a Love Story. This was a watershed year in the history of Hong Kong cinema, marking the end of the city’s colonial rule: a good many Chinese and Taiwanese films and videos of 1997, narratives as well as documentaries, addressed the subject directly. One of the better of these efforts, Wong Kar-wai’s Happy Together — which for most of its length addresses the subject indirectly — will be opening here in a couple of weeks. But for me the most moving reaction to this momentous event is Peter Chan’s lyrical and heartfelt love story, set between 1986 and 1996, which played at the Film Center four times in late August. Starring Maggie Cheung and pop star Leon Lai, this youthful and semitragic tale about two Chinese mainlanders who meet in Hong Kong and eventually emigrate separately to New York swept nine categories (including best director, film, screenplay, and actress) at last year’s Hong Kong Film Awards. At least as much as Titanic, it qualifies as a millennial statement, catching the spirit of the times like few other pictures; its recurring shots from within an ATM are only one instance of its wit and invention.

Before proceeding to my list of honorable also-rans, I’d like to cite two substantial and important films that were seriously damaged by insensitive recutting — William Gazecki and Dan Gifford’s documentary Waco: The Rules of Engagement and Chen Kaige’s Temptress Moon. In both cases this mutilation was carried out to appease the sort of dim-witted industry reviewers, in both trade papers and the mainstream press, whose sole motive seems to be telling dim-witted producers or distributors what they want to hear.

Next in line are a number of important, accomplished films that went through town so quickly that if you blinked you missed them: Flora Gomes’s 1995 Po di sangui, a formally beautiful pageant from Guinea-Bissau that turned up at Columbia College in March; James Benning’s Four Corners, an experimental feature that showed twice in somebody’s loft last month; Edward Yang’s most recent feature, Mahjong, which turned up during his Film Center retrospective; three solid entries at the Chicago International Gay and Lesbian Film Festival in November, Ira Sachs’s The Delta, Su Friedrich’s Hide and Seek, and William E. Jones’s Finished; Philippe Garrel’s piercing The Birth of Love (1993), which ran at Facets Multimedia in June; two refugees from the Telluride film festival that surfaced at the Film Center in September, Nicholas Barker’s oddball documentary Unmade Beds and Alexander Sokurov’s painterly Mother and Son (the latter returning to the Music Box for a full run this February); and five worthy features shown only at the Chicago International Film Festival in October (though the last two will be returning): Tsai Ming-liang’s The River, Yim Ho’s Kitchen, the collectively made French-Canadian sketch film Cosmos, Manoel de Oliveira’s Voyage to the Beginning of the World (featuring the last performance of Marcello Mastroianni), and Richard Kwietniowski’s witty Love and Death on Long Island. (Susan Dryfoos’s delightful documentary The Line King: The Al Hirschfeld Story passed through town quickly at the Silver Images film festival in May, but you might have caught up with it later at the Village North.)

Eleven additional movies strike me as being collectively superior to the 25 multiplex favorites given at the beginning of this survey. Again listed in order of preference, the honorable mentions are Olivier Assayas’s Cold Water, Sally Potter’s The Tango Lesson, Peter Greenaway’s The Pillow Book, Raul Ruiz’s Three Lives and Only One Death, Mohsen Makhmalbaf’s A Moment of Innocence (which I prefer to his Gabbeh), Peter Duncan’s Children of the Revolution, Lars von Trier’s Medea, Jonathan Nossiter’s Sunday, Tomas Gutierrez Alea’s Guantanamera, Wim Wenders’s The End of Violence, and Benoit Jacquot’s A Single Girl.

Last year was also a pretty good one for revivals. A beautiful restoration of Godard’s Contempt showed at the Music Box in September, and my favorite film by Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Martha (1973), which had never been shown in Chicago before, was a highlight of the exhaustive midyear Fassbinder retrospective at the Film Center and Facets Multimedia. Even better were the prerelease version of Howard Hawks’s The Big Sleep, which showed at Facets in June, and the original version of Carl Dreyer’s last silent film, The Passion of Joan of Arc, shown at the Medinah Temple in February to the strains of Richard Einhorn’s Voices of Light, memorably performed by Anonymous 4, the Los Angeles Mozart Orchestra, and the Zephyr Chorus.

But my annual F.W. Murnau award to the film that did the most to alter my sense of film history has to go to the restoration of Fritz Lang’s seminal M, which played at the Music Box in August. It harks back to a period when it was still possible to believe one could embrace and understand the complex interactions of a large city from top to bottom — a possibility now lost to us thanks to the vagaries of cyberspace and video — and no film in the history of movies does more with that belief than Lang’s masterpiece.