From Monthly Film Bulletin, September 1976, , Vol. 43, No. 512. I believe that this is the first time I wrote about Moullet. — J.R.

Steack Trop Cuit, Un (Overdone Steak)

France, 1960

Director: Luc Moullet

Cert-U. dist–Connoisseur. p.c–Les Productions Luc Moullet/Les Productions Georges de Beauregard. p–Georges de Beauregard. 2nd Unit d–Pierre Guinle. sc–Luc Moullet. ph–André Mrugalski. 2nd Unit ph–Raymond Cauchetier. ed–Agnès Guillemot. 2nd Unit ed–Maryse Siclier. a.d–Luc Moullet. m–Frédéric G. Ploumepeux. English titles— Mai Harris. sd–Marielle Lesseps. cooking adviser–Alberta Laguioner. /.p–Françoise Vatel (Nicole), Albert Juross (Georges), Jacqueline Fynnaert (Françoise), Raymond N. Quinneseul (Samuel). 1,739 ft. 19 mins. Subtitles.

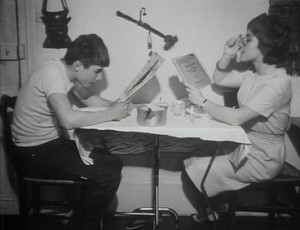

Returning home from school, Georges protests angrily to his older sister Nicole that she hasn’t yet prepared dinner. With both their parents away, she is in control of his pocket money, and threatens not to give him any for Sunday after he behaves boorishly. Claiming that the steak she has cooked is inedible, he goes next door and borrows sausages from their neighbour Françoise, which he gets Nicole to prepare. Afterwards, he plays footsy with Nicole at the table and talks to her while she puts on make-up and changes clothes, preparing to go out on a date. After she leaves, he goes into the kitchen to wash up and begins to smash the dishes.

A genuine curiosity piece and relic from the early days of the New Wave, Un Steack Trop Cuit is the first film to have been made by Luc Moullet — one of the more fascinating critics on Cahiers du Cinéma during that period and currently a producer, although he has made at least five other films (three of which are features, and none of which is available in England) in the interim. Evocative at times of both Godard’s 1958 short Charlotte et Son Jules and some of Chabrol’s early studies of bêtise, its plot mainly consists of its young hero’s contemptuous treatment of his sister (“I act this way so you won’t be bored. You should be grateful”) and his obnoxious table manners — eating with his fingers, sucking juice off his plate and noisily spitting out pieces of food. (When she asks him for the time, he replies, “At the sound of the third belch, it’ll be exactly 7:49”, and promptly illustrates; later, he picks a strand of spaghetti off the floor and places it on her plate with the line, “Tu es vraiment dégueulasse”, echoing Belmondo’s last words in A Bout de Souffle.) Among the various New Wave tropes are a same-field jump cut, a sudden cutaway shot to brother and sister glimpsed in an oval mirror. and the obligatory Cahiers reference (when Georges repairs to the toilet and asks Nicole to pass him paper under the door, she winds up shredding a recent copy). While all the above might be regarded as rather pointless doodling — all the more gratuitous in a short which oddly boasts a second-unit director, cameraman and editor in its credits — a subtext of complicity and affection between the siblings gives the film a rather poignant aftertaste. Georges, we discover at one stage, is a student who makes high grades while Nicole is seriously worried about passing her exams, and Moullet’s remarks about his work as a whole in Cahiers No. 216 (“Mes films, eux, sont très orientés sur le problème de l’intelligence-bêtise”) suggests a rather special terrain where the qualities of intelligence and stupidity are deliberately made indistinguishable — an interest certainly evident in Moullet’s third feature (with Jean-Pierre Léaud, about Billy the Kid — aptly described by the director as a mixture of Duel in the Sun and Les Dames du Bois de Boulogne), and apparently present in such earlier deconstructive dada as Brigitte et Brigitte and Les Contrebandières. It helps to explain, in any case, why Moullet has been described as the Alfred Jarry of the New Wave, praised at length by Godard, and singled out by Straub as “the most important film-maker of the French post-Godard generation”.