Written for MUBI in early August 2021. MUBI decided not to run it because of its borrowings from an earlier piece of mine that ran in Sight and Sound in 1983 (see link below: https://jonathanrosenbaum.net/2019/03/on-chan-is-missing-and-wayne-wang/), which is why I’m posting it here.– J.R.

It’s a sad fact that when certain filmmakers fail to perform the narrow tribal duties assigned to them by the marketplace, they risk floating off the map of our awareness. For the past sixteen years, ever since I reviewed one of his lesser efforts (Because of Winn-Dixie, 2005), Wayne Wang has drifted out of my consciousness, not because he’s been inactive but because I’ve seen none of his last seven features and his media profile has been too scattered to produce many ripples in the American mainstream. Yet in a culture where it’s still frowned upon to insist that Barack Obama is half-white, that two of Roman Polanski’s recent and undistributed and/or ignored movies (Venus in Fur and Based on a True Story) qualify as feminist antocritiques, and that Spike Lee’s most accomplished and affecting feature, 25thHour (2003), has nothing to do with being black, the failure of Wayne Wang to stick exclusively to his perceived roots (Hong Kong, American, Chinese-American) has prevented him from becoming or remaining a household name. And now that Chan is Missing (1982), his first hit, has been restored and is getting rereleased, it’s a good time to consider what’s been keeping him out of sight—meaning only my sight and possibly yours, but certainly not everybody’s.

For starters, the fact that he’s moved between Hong Kong and northern California has meant contending with a split identity as well as a split audience. Significantly, he was born in British Hong Kong in 1946, and named after his father’s favorite movie star, John Wayne. He emigrated to the U.S. at 17, where he studied film and television in Oakland. Although Chan is Missing is the film that established him in 1982, it was preceded by lesser-known work in the mid-70s. His whole career, in short, resists the tidy cataloguing that we associate with branding, and an uneven track record with some of his work for hire makes him still harder to assess. Characteristically, his two most recent releases are a Japanese feature produced by and starring Takeshi Kitano (While the Women are Sleeping, 2016) and a U.S. feature about Korean Americans (Coming Home Again, 2019).

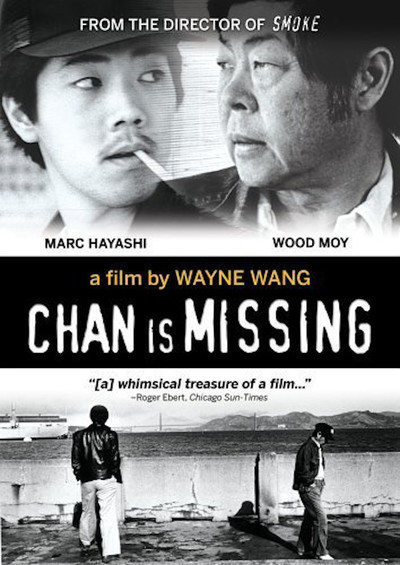

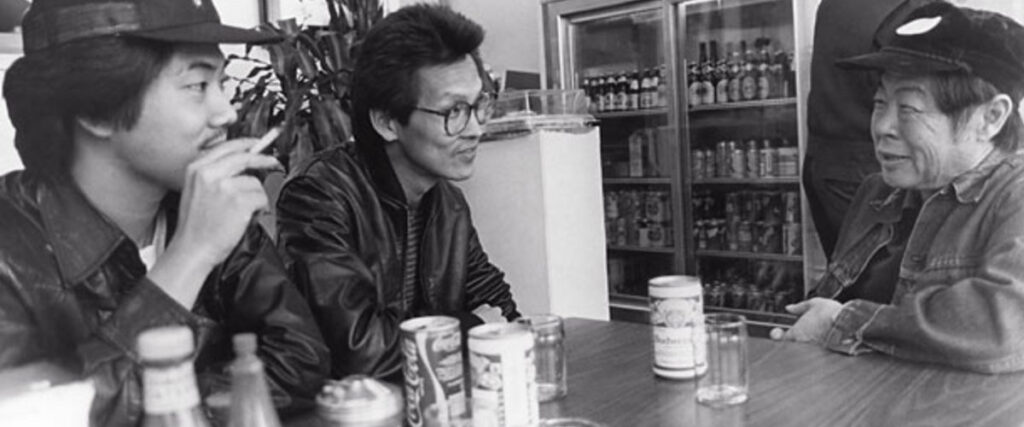

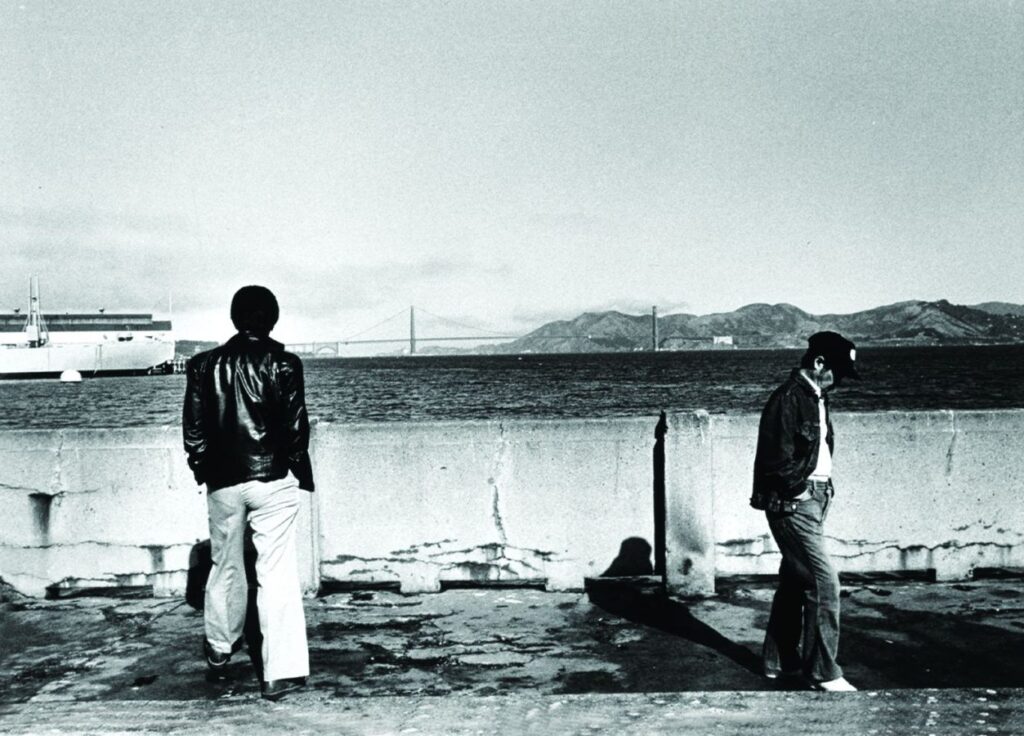

Chan is Missing opens with a rousing Cantonese version of “Rock Around the Clock” whose lyrics are about inflation — the rising costs of rice, sugar, tea, and even soy sauce — whichneatly combines a concern about what it means to be Chinese-American with the then-current economic crisis. This is only the first of many effective uses of borrowed music with funky location shooting and punchy editing whose economy, moreover, is part of its meaning. Fueled by a $10,000 American Film Institute grant and eventually costing less than twice that amount, the film grew out of the ancient cliché about Chinese-Americans embodied by the Hollywood gumshoe Charlie Chan. A black and white mystery about two cab drivers, the older Jo (Wood Moy) and the younger Steve (Marc Hayashi) searching for their missing partner Chan through San Francisco’s Chinatown, it was shot over ten weekends during the summer of 1980 after a lengthy period of writing.

“Originally it was something else that involved a black taxi driver and the whole black community,” Wang told me when I interviewed him back in the early 80s. ”And then I dropped {it] because I didn’t feel I really had a grip on it. Then it got real structural; I showed that script to the cast and crew, and they had problems with it. So I started changing the script into something that was more narrative and more linear. That went on for about a year.”

``Wang went on to describe to me the theoretical and structural basis of the script when it was based on the evolution of the Chinese written word in relation to images, which also had influenced the montage theories of Sergei Eisenstein. (Some of this approach survives in a hilarious monologue by a young female lawyer about “the legal implications of [the] cross-cultural misunderstandings” that arise between Chan and a traffic cop over whether or not he stopped at a stop sign.) “So the idea was to base the whole mystery on that structure and evolution. But since this was obviously going to be the first major Chinese-American film done in this country, it seemed a little selfish to do this structural film rather than something that’s more accessible to more people. At the same time I [didn’t] want to give up some of the things I really wanted to do with films. So that’s why the ending of Chan is Missingmoves from something very specific to something that’s much more structural and abstract, where there are literally flash frames in the water shots…” Even though the mystery remains perfunctory and is never resolved, the easygoing natural performances, colorful milieu, and warm humor keep it lively and entertaining.

Another Wang movie that I like a lot, Life is Cheap…But Toilet Paper is Expensive(1989), is close enough to Jean-Luc Godard that it could have been called 2 or 3 Things I Know about Hong Kong. Yet its provocations when it first surfaced, beginning with its title, offended so many colleagues, Asian and non-Asian alike, that I suspect it might have nipped Wang’s growing reputation in the bud. Partly a poetic documentary about his home town both as a nest of movie references and as a city about to join the mainland in 1997, it was also a thriller featuring one of the longest chase sequences ever filmed. But its intellectual aspects broke with the models of no-brain action kicks favored by the more influential fans of Hong Kong martial arts movies (including both Tarantino and some academics), and its dark comedy and its politics didn’t help it to garner any industry approval. You might even say, to its credit, that it was asking for trouble.

And even more than Godard — perhaps more like Alain Resnais, whose U.S. profile i s equally blurry — Wang tends to reinvent himself with each of his more ambitious projects, thereby jeopardizing his status as a marketable (i.e, predictable) auteur. Whereas a Woody Allen can nearly always be counted on to mimic either a Bergman or Fellini film with every new picture, Wang can emulate Godard in Life is Cheap, Yasujiro Ozu in Dim Sum: A Little Bit of Heart (1985), and Kenji Mizoguchi in The Joy Luck Club (1993), thus complicating his multicultural media profile beyond easy sound-bites.