From the Chicago Reader (July 23, 2004). — J.R.

The Corporation

The Corporation

**** (Masterpiece)

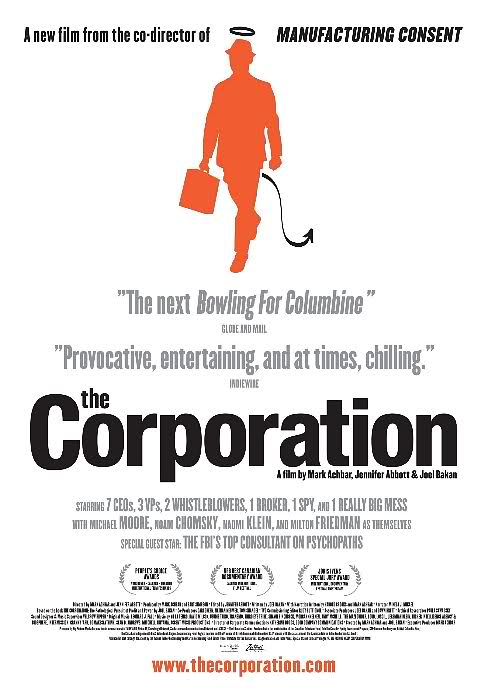

Directed by Mark Achbar and Jennifer Abbott

Written by Joel Bakan, Harold Crooks, and Achbar

Narrated by Mikela J. Mikael.

A month ago I attended back-to-back press screenings of two major documentaries, Michael Moore’s Fahrenheit 9/11 and The Corporation, which finally opened here last week. Though it would have broken with industry protocol to have said so at the time, before both movies had opened, it was clear that The Corporation — a 2003 Canadian film by Mark Achbar, Jennifer Abbott, and Joel Bakan — was a better film, and second looks at both movies has only confirmed this impression. Michael Moore’s movie probably startles people who rely mostly on TV for their news, but The Corporation will shock even those who keep close track of newspapers and magazines. In fact, it goes beyond shocking in obliging us to ask ourselves how far we’re all prepared to go in our defense of capitalism.

Far enough to jeopardize our health and the survival of the planet? Maybe not, but at the moment it’s corporations that appear to have the power to decide. And the stories this film uses to demonstrate that are chilling. I’m reminded of Vladimir Nabokov’s description of the spark that led to Lolita: “As far as I can recall, the initial shiver of inspiration was somehow prompted by a newspaper story about an ape in the Jardin des Plantes who, after months of coaxing by a scientist, produced the first drawing ever charcoaled by an animal: the sketch showed the bars of the poor creature’s cage.”

This riveting cinematic essay includes no less than 40 talking heads, ranging from writers such as Noam Chomsky, Milton Friedman, Naomi Klein, Michael Moore, and Howard Zinn to CEOs such as Ray Anderson (of Interface, the world’s largest commercial carpet manufacturer), Sam Gibara (Goodyear Tire), Robert Keyes (Canadian Council for International Business), Chris Komisarjevsky (Burson-Marsteller Worldwide), and Sir Mark Moody-Stuart (Royal Dutch/Shell). The wide variety of voices — roughly a quarter of which belong to women — and the cogent narration, written by Harold Crooks and Achbar, make for a highly entertaining and instructive look at a subject that’s rarely discussed in detail.

Michael Moore’s presence in both films suggests that they should be regarded as complementary. The Corporation is more intellectual and nuanced, Fahrenheit 9/11 more emotional and direct. The Corporation is more interested in concepts, Fahrenheit 9/11 in personalities. Both are unambiguously leftist and activist. The Corporation is much harder to describe, which may be why it isn’t receiving the media attention lavished on Fahrenheit 9/11. Yet what it has to say about the future of the planet and the way we live is even more compelling.

I can’t think of another documentary that’s taught me as much as this one. I hadn’t known, for example, that the song “Happy Birthday” is owned by Time Warner (which expects to be paid every time it’s sung in a movie), that for a spell Bechtel controlled the use of water in Bolivia’s third-largest city (the contract even prohibited collecting rainwater), that one can legally patent “anything that’s alive except for a human being” (including genes and microbes), that Fanta Orange was created because Coca-Cola wanted to do business in Nazi Germany (where IBM punch cards were used to collate information on concentration-camp prisoners), or that, according to a recent U.S. Treasury report, in one week alone 57 American corporations were fined for trading with official enemies of the U.S., including terrorists.

This 145-minute movie may not send us out of the theater with the kind of simple directive Fahrenheit 9/11 did in implicitly urging us to vote a president out of office, but it doesn’t encourage us to accept our situation either. It also shows us how activism has already made a difference — how massive street demonstrations in Bolivia eventually gave Bolivians free access to water again and how residents in Arcata, California, managed to block more chain restaurants from moving in.

The Corporation refuses to limit its argument to sound-bite problems with sound-bite solutions. It starts out with a hilarious critique of the use of one sound-bite term, “bad apple,” when discussing corporate malfeasance. (The same criticism could be made of its use in discussions of torture at Abu Ghraib.) We see a dozen routine, glib examples of its use before the narrator asks, “What’s wrong with this picture? Can’t we pick a better metaphor?” After summoning up a host of alternatives — including “jigsaw,” “sports team,” “family unit,” “telephone system,” “eagle,” “big fish,” and “Frankenstein monster” — the film plunges into a fascinating account of how corporations as we know them today were developed by lawyers from the mid-19th through the early 20th centuries. It ties corporate growth to the Industrial Revolution and the Civil War — and to the 14th Amendment, which was intended to protect the rights of former slaves but later was used to define corporations as if they were persons. We’re told that of the 307 14th Amendment cases brought before the Supreme Court between 1890 and 1910, 19 were brought by African-Americans, 288 by corporations.

If, legally speaking, corporations are like people — enjoying many of the same freedoms, though saddled with few of the same responsibilities — what kind of people are they? Analyzing corporations the way psychiatrists analyze patients and offering a “personality diagnostic checklist” of diverse “psychic disorders,” The Corporation maintains that the behavior of corporations is often psychotic — a premise that’s less fanciful than it sounds if we bear in mind that sanity is more a social and legal concept than a medical one. Arguing this position seems like a lawyer’s tactic, so it’s no surprise that Bakan, the main scriptwriter, is a lawyer.

Like Fahrenheit 9/11, The Corporation is a critique of the mass media, but it’s also smart enough to know that it’s part of the same corporate world it’s exposing. This leads to an especially funny and clever interlude about what it calls “real-life product placement,” in which it uses itself as a prime illustration, and to a pithy explanation from Moore of why some corporations are willing to sponsor his anticorporate shenanigans. We also get a detailed account of how Fox News systematically suppressed two reporters’ evidence of health hazards in milk containing bovine growth hormone — a hormone banned in Canada and Europe but left on the market here because it generates such big profits.

This is a heavy documentary, yet one with a remarkably light touch when articulating even its scariest points. Any movie that can use portions of a campy instructional film from half a century ago to further as well as mock some of its own positions clearly has an advanced sense of rhetoric, not to mention an imaginative grasp of filmmaking possibilities. Above all, this movie’s flair in using anything and everything to build its argument with seamless continuity makes it easy to watch.

Corporate psychoses that lead to corporate offenses are the main bill of fare here, yet the interviewee who registers as most heroic and charismatic isn’t Chomsky (even if he’s less hyperbolic than usual) or Moore (even though he delivers the film’s eloquent last words). It’s Ray Anderson, whose account of how he came to understand environmental concerns and made sustainability the watchword at his carpet company is probably the most meaningful personal story this film has to tell. More broadly, the decision not to divide the world neatly between heroes and villains, as Fahrenheit 9/11 does, encourages us to see the solutions to problems as complex rather than as a simple matter of picking the right political party.