Commissioned by a Spanish-language retrospective catalogue devoted to Richard Linklater. — J.R.

A prefatory caveat

My favorite Richard Linklater feature, Bernie (2011), is many different things at once, some of which are in potential conflict with one another. How we ultimately judge it depends on either reconciling or suspending our separate verdicts on how we judge it as fiction (and art) and/or how we judge it as fact (and justice). Because I’ve chosen to suspend my judgment on how we can judge the film as fact, for reasons that will be dealt with below, I can enjoy the luxury of celebrating the film as fiction and as art at the same time that I would maintain that it opens up factual questions about truth and justice that it can’t pretend to resolve in any definitive manner.

1. Background

The film was inspired by a lengthy article, “Midnight in the Garden of East Texas” by Skip Hollandsworth, that appeared in the January 1998 issue of Texas Monthly, about the confessed murder of Mrs. Marjorie Nugent, an 81-year-old widow and the wealthiest woman in town, by 39-year-old Bernie Tiede, a former assistant funeral director in the same town (Carthage, with a population of 6,500) who had become her paid companion and the sole inheritor of her considerable fortune. After having shot Marjorie Nugent four times in the back with a .22 rifle and stored her body at the bottom of a large freezer in her home for over half a year, Tiede confessed to the police after the widow’s son and his eldest daughter searched the house and discovered her body.

As Hollandsworth describes the local impact of the crime’s discovery, Tiede was the most beloved member of the community, someone who had generously spent most of the money he had pilfered from Nugent (perhaps the most hated member of the community for her miserly traits, social snobbery, and ill temper) on others who needed it. And as suggested by the title of Hollandsworth’s article — prompted by John Berendt’s best-selling “non-fiction novel” Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil (1994) and the 1997 Clint Eastwood film derived from it, about the killing of a male prostitute by a wealthy antiques dealer in Savannah, Georgia—Hollandsworth was more interested in the crime’s local impact and what this said about the town itself than he was in the crime. The fact that East Texas is “Southern” (close to the border of Louisiana), with a distinctly different culture from other portions of the state, is deftly and colorfully outlined in detail by one of the locals, Sonny Davis, early in the film, complete with animated maps behind him to illustrate his various points. That Linklater himself hails from east Texas, where one of his other most personal and inspired features is grounded (The Newton Boys, 1998, also based on a true story), obviously sparked his interest in the story and characters. Significantly, both The Newton Boys and Bernie are anarchistic and humanistic defenses of sympathetic criminals, although the crimes committed in the former are exclusively bank robberies. That Bernie mounts a comic defense for a thieving murderer makes it far more subversive and challenging, especially insofar as this defense is made to seem implicit and even secondary: its principal aim is to celebrate the humor, eccentricity, and personalities of a small town in east Texas, including the various moral paradoxes involved in its language and discourse.

A dozen years would pass between the appearance of Hollandsworth’s article and the film’s production, and not only did Linklater enlist Hollandsworth as his cowriter during this period; his script follows the particulars of the original article quite closely, meanwhile updating it to include the subsequent trial (which was held almost 50 miles away from Carthage, in San Augustine, due to the partiality of Carthage residents towards Tiede), which both Linklater and Hollandsworth attended. There is one significant omission, however — the possibility (broached in Hollandsworth’s article but missing from the film) that Tiede’s confession of the murder may have been prompted by the fact that, after the discovery of Nugent’s corpse, “deputies had confiscated nearly fifty videotapes from Bernie’s house, some showing men involved in illicit acts”. Although Tiede being a homosexual is not exactly overlooked in Linklater’s film — we hear this euphemistically expressed as gossip that “Bernie was a little light in the loafers” — any hint of an active sex life in Carthage as a gay man is carefully avoided, perhaps because this would complicate the story and its various ramifications well beyond Linklater’s own narrative agenda.

Further complications ensued after Tiede was sentenced to life imprisonment for first-degree (premeditated) murder, a sentence that is said to have been prompted largely by Tiede’s handwritten confession. In May 2014, based on the argument that, after having been sexually assaulted as a child, Tiede committed the murder during a brief “dissociative episode” brought on by Nugent’s abuse of him, Tiede was released on $10,000 bail in the custody of Linklater and allowed to live in his garage apartment in Austin. But almost two years later, in April 2016, Nugent’s granddaughter, who had alleged that Linklater’s film had unjustly led to Tiede’s release, was able to get him retried, and Tiede was returned to prison for a life sentence, which he is currently serving.

2. Foreground

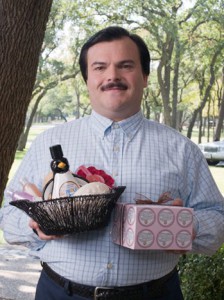

‘WHAT YOU’RE FIXIN’ TO SEE IS” and ‘A TRUE STORY” are the film’s first two intertitles, both quaintly decorated in the style of silent movies, with praying hands and creeping vegetation. And the colloquial ring of the first intertitle both qualifies and focuses the didactic ring of the second. Both intertitles punctuate an academic lecture-demonstration by Bernie (Jack Black) on how to make a corpse presentable, a spectacle that is no less a blend of fact and folksy patter (“A little dab will do you”.) This prepares us for the third intertitle, “’WHO IS BERNIE?’”, which immediately follows, along with the movie’s credits and Bernie robustly singly “Love Lifted Me” along with his car radio as he speeds down a leafy highway, entering and driving through portions of Carthage. This is intercut with shots of various Carthage residents in different locations praising him directly to the camera, before we arrive at Sam’s Bar BQ, where inside the premises Sonny Davis delivers his aforementioned illustrated lecture about the separate partitions of Texas — yet another example of factual exposition delivered through flavorsome artifice. As in much of Linklater’s other work, what identifies itself as and pretends to be a “story” is mainly a set of characters and a milieu, a celebration of a particular culture and a style of living.

Separating fiction from non-fiction in this volatile mixture is no easy matter. The film’s final credits, after a few glimpses of the real-life Bernie and Marge (including a shot of the former in prison, conversing with Jack Black) identifies all the actors with miniature clips, starting with ten professionals (including Jack Black as Bernie, Shirley MacLaine as “Marge” Nugent, and Matthew McConaughey as local district attorney Danny Buck Davidson) before proceeding to thirty-one non-professional “townspeople”, but it isn’t always clear whether the latter are using their real names. (My favorite “townsperson”, identified in the credits as “Kay Epperson”, is addressed by Bernie/Jack Black as “Lenora” when we see her visiting him in prison.) And we already know from some of the earliest examples that we have of “documentary” and “fiction” cinema — the Lumières staging comical “real-life” events for their cameras, Méliès re-enacting “current events” with actors, Flaherty casting his own Eskimo mistress to play Nanook’s wife — that the protocols for making clear distinctions often amount to con games, or at the very least intricate mixtures of fact and fancy.

We don’t see enough of Bernie Tiede’s (first) trial to determine whether the harsh sentencing is the result of evidence for premeditated murder or cultural bias, but Linklater takes some pains to suggest that cultural bias plays a major role, especially when the cross-examination of Bernie/Black by Danny Buck/ McConaughey focuses at length on a trip to New York taken by Bernie and Marge and their first-class air tickets, attending Les Miserables (grotesquely mispronounced by Danny Buck, correctly pronounced by Bernie), and knowing what wines should be drunk with fish, capped by Danny Buck’s declaration, “That takes a lot of money to have culture so much, don’t it? To enjoy the finer things in life that you know so much.” Coupled with all the cultural activities in Texas that we’ve previously seen Bernie attending (often with Marge), participating in, and/or promoting or financing — classical music concerts, productions of musicals such as Guys and Dolls and The Music Man (with Bernie directing and playing leading roles), and a good many funerals, along with many other civic activities — this offers an adroit encapsulation of the American hatred for “art” as a form of social snobbery that Danny Buck is counting on. Indeed, we’re even left with the plausible presumption that it’s Bernie’s reverence for and support for the fine arts that helps to sentence him to life imprisonment.

Linklater’s grasp of this attitude is complicated by a clear fondness for East Texan folkways that can also allow for affectionate satire and ridicule of hyperbole and other excesses. The same ambivalence towards his characters is fully evident in his most recent feature, Everybody Wants Some!!, set in 1980, as it is in his other “period” films set in Texas, e.g., Dazed and Confused (1993, set in 1976) and The Newton Boys (1998, set mainly in the 1920s).

Apart from Alaska, Texas is the largest state in the U.S., and one of the identifying traits of the country as a whole is a solipsistic conviction that it represents the entire cosmos, leading to the potentially dangerous and disastrous belief that this cosmos consists exclusively of Americans and “failed” Americans — the latter category composed of people who either want to be American or want to destroy America. Within this solipsistic mindset (which can arguably be also be found to some degree in other large countries, such as Russia and mainland China), “Texas” is therefore another version of “America” reduced to its (perceived) essence. And “East Texas” is little more than a further refinement of the same concept — which is why both Hollandsworth’s article and Bernie emphasize the fact that Carthage “made it into the 1995 edition of The Best 100 Small Towns in America.”

As a humanist with anarchistic impulses, Linklater honors all his characters in different ways, but apart from the magnificence of Jack Black in his multifaceted performance, it is the thirty-one townspeople and their choral role that dominate the proceedings. Indeed, defining Bernie apart from his community becomes an impossible task.