From the Chicago Reader (December 19, 2003). — J.R.

Stuck on You

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Bobby and Peter Farrelly

Written by Bobby and Peter Farrelly, Charles B. Wessler, and Bennett Yellin

With Matt Damon, Greg Kinnear, Eva Mendes, Wen Yann Shih, Cher, Seymour Cassel, Griffin Dunne, and Meryl Streep.

One of my all-time favorite Japanese movies is Yasuzo Masumura’s A Wife Confesses (1961), which I’ve been able to see only once, in Tokyo with a live English translation. It’s a courtroom thriller about a young widow who’s being tried for her part in the death of her abusive older husband while they were mountain climbing, and it hinges on the haunting question of what she was thinking when she made the split-second decision to cut the rope connecting the two of them. She was attached at the other end of the rope to an attractive young man who had business ties to her husband and with whom she was in love, and she had to cut one of the men loose to prevent all three of them from plummeting to their deaths.

The story is a tragic allegory about the interdependence of individuals in Japanese society and how this conflicts with individual choice and desire, and I can’t imagine it being remade in this country, where the rightness of the heroine’s choice would more likely be regarded as self-evident. Similarly, I have a hard time imagining how Stuck on You — a hilarious yet ideologically tricky slapstick comedy by bad-taste maestros Bobby and Peter Farrelly about Siamese twins joined at the hip — could have been conceived, much less made, in any country but this one.

The reason isn’t the bad taste or the lowbrow high jinks, both of which are found in abundance in other cultures. It’s the sleight of hand — or sleight of mind — that simultaneously ignores and embraces, denies and seizes upon the condition of being Siamese twins. This sleight of mind — now you think it, now you don’t — becomes a kind of ideological fan dance that makes viewers feel extremely open-minded even though they haven’t been challenged. Some ads for the movie prompt the same response. “Outrageous comedy and a lot of heart are joined at the hip in Stuck on You,” says one — grotesquely mixing metaphors — while pictures show the lovable brothers playfully placing their fists knuckle to knuckle; the caption reads “Brothers Stick Together,” but their hips aren’t shown, as if to say, too explicit isn’t funny.

A lot of heart? I guess you could say the picture has that. Yet I doubt real Siamese twins are the focus of this heart. Indeed, the warmth seems possible mainly because brothers Bo (Matt Damon) and Walt (Greg Kinnear) are familiar — not because we know what real Siamese twins have to contend with, but because these are familiar actors playing familiar roles.

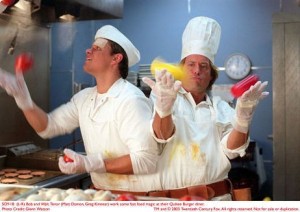

Their characters are a quarrelsome yet generous pair who get in each other’s way while trying to help each other out but also work smashingly well as a team. Class differences seem to matter a lot more in this movie than physiological differences — a distinction that’s hardly new to the Farrelly brothers. Bo and Walt run a burger joint in Martha’s Vineyard that employs a mentally challenged waiter who speaks with a stutter (played by someone with this disability), and the brothers pride themselves on how quickly they can fill orders and how gracefully they eject an irate couple who regard the staff as freaks.

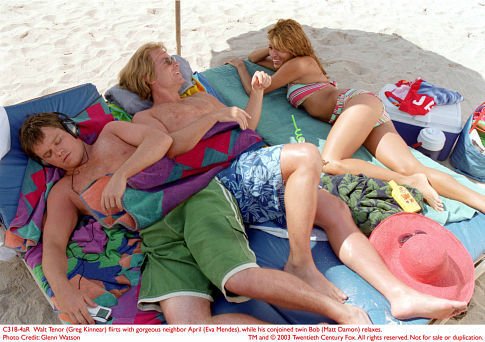

In the terms propounded by this movie, cruelty toward the disabled and snobbery are opposite sides of the same coin, but society is good-hearted enough to accept Siamese twins taking part in everyday activities whenever possible, including baseball, prizefighting, and theater. That Walt has acting aspirations while Bo suffers from stage fright is undoubtedly a problem, but it’s one that derives from their own disparate personalities. When Walt decides they should move to Hollywood to pursue “his” acting career he isn’t being entirely selfish, because he knows that Bo’s e-mail pen pal May lives in the area. Walt’s implicit denial that being a Siamese twin will seriously hamper his acting career is matched by Bo’s denial to May that he’s physically connected to Walt, and the resulting farcical complications stem in part from the social protocols and denials that inhibit Walt’s employers and May.

The denial at the heart of this comedy gives it unusual potency because the current political discourse in this country has been shaped by denial. In order to justify the invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq the Bush administration is in denial about, among other things, this country’s support for and arming of Osama bin Laden and Saddam Hussein, intelligence showing that Iraq had destroyed most if not all of its programs to build weapons of mass destruction, and high-level warnings that Iraq could turn chaotic once the Iraqi army was defeated. Whatever one thinks of the Bush administration, we’re all affected by this kind of denial.

I had lots of qualms before I saw Stuck on You, yet I have to confess it made me laugh a lot. The Farrelly brothers’ grasp of social embarrassment is strong enough that I was able to identify on some level with the Siamese twins — though on a level so tenuous only their sleight of mind made it possible. I haven’t seen the Farrellys’ Shallow Hal, but Elizabeth Tamny’s review in the November 16, 2001, Reader suggested that it displays a similar sleight of mind regarding fat people: “You get the feeling the movie mops itself into an ideological corner. With its thin version of a fat heroine and two-second glimpses of fat body parts, Shallow Hal is about as close as we want to get to the life of a fat person for now.” Siamese twins are even less common than fat people, so we’re probably less sure how close we want to get to their lives.

A complicated mechanism is at work here. Stuck on You is a brilliant enactment of the comedy of denial, yet it also requires lots of denial on the part of the filmmakers and the audience. This is especially true once Walt starts costarring in a sitcom with Cher (playing herself); it immediately becomes a hit, changing his working-class, working-stiff status — though he and the movie deny that it has. He and Bo, for instance, continue living at the same fleabag hotel. Adding to the doublethink is the extensive use of real celebrities and media institutions to validate the twins’ unreal world: not only Cher, but Griffin Dunne, an uncredited Meryl Streep, Jay Leno, and the Tonight Show, which serves in this movie’s terms as the ultimate public validation. Cleverly, the real-life Cher has been persuaded to play herself as a hyperbolically scheming bitch — which allows her to apologize later in the plot for having been one — and Streep is invited to be hyperbolically polite to Walt when he encounters her in a restaurant.

Once the twins decide to risk a dangerous operation separating them, permitting Bo to return to Martha’s Vineyard and the burger joint while Walt remains in Hollywood, the psychological bond that ultimately brings them back together becomes central to the story, and the class issues that have come between them are dropped. Most improbable of all, the twins wind up in the best of all possible worlds: back at the burger joint consorting with just plain folks. And when Walt realizes his dream of staging and starring in a local musical based on Bonnie and Clyde, Cher and Streep are converted into just plain folks too, Cher turning up in the audience to cheer him on, Streep gamely serving as his costar. (Significantly, neither actress is seen at the burger joint, but the disabled waiter working there is in the stage musical, which may be just as good at leveling the playing field.) As a surefire closer, the musical is allowed to take over the movie, supplanting all the unresolved class issues it has been cheerfully denying all along. This too has a particular kind of contemporary relevance if we think about Enron being overtaken by Afghanistan, Afghanistan being overtaken by Iraq, and good intentions regarding both countries being overtaken by ignorance and confusion. When in doubt, change the subject.