From The Soho News (April 22, 1981). — J.R.

April 7: The Story of Three Loves (1953) at the Regency. It’s been over 27 years since I last saw this luscious, kitschy technicolor trio of thematically related sketches — awkwardly and arbitrarily stitched together on an intervening ocean liner — and it impresses me even more now than it did at age 10. Its terrain is neither Hollywood nor Europe, exactly, but a glossy MGM compromise between American dreams of Europe and European emigré dreams of America. And the fascinating thing about it today is the degree to which pop existentialism composes its principal form of hard aesthetic and social currency, in all three of its delirious parables about love and art.

In the London-based “The Jealous Lover” (scripted by John Collier, directed by Gottfried Reinhardt), ballerina Moira Shearer learns she has a weak heart that prohibits further dancing. Subsequently inspired, however, by the florid imagination and genius of director James Mason, she devotedly and ecstatically dances herself to death.

“Mademoiselle” offers Vincente Minnelli’s mise en scène of a Rome-based fantasy about an 11-year-old Ricky Nelson patterned somewhat after Daisy Miller’s twerpy kid brother. Secretly infatuated with his governess, Leslie Caron, he is enabled by the magic of an obliging American witch (Ethel Barrymore) to become Farley Granger for one enchanted, Cinderella-tense evening.

Finally, in the Paris-based “Equilibrium” (another wry Collier-Reinhardt episode), two sexy, doomed existential hero/victims, Kirk Douglas and Pier Angeli — each responsible for a spouse’s death through an unlucky gamble — team up as trapeze artists who fall simultaneously in love and out of their profession only after they gamble on each other without a net, and win.

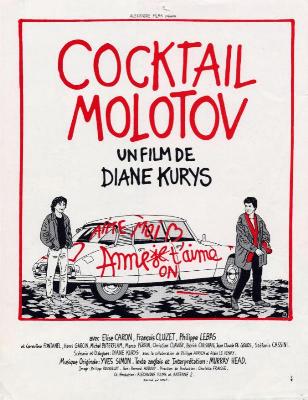

What seems rather amazing about all this today is how up to date it once was — a movie that appeared the same year as the English translation of Sartre’s Being and Nothingness, and a good four years before Mailer’s “The White Negro”. In striking contrast, Diane Kurys’ dippy Cocktail Molotov — a “contemporary” French film about May ’68, opening Sunday at the Baronet, that I see right afterward — looks genuinely reactionary, even for 1979.

If I understand the task of this film correctly, it is more or less an attempt to depict May ’68 for teenagers today in a manner that renders it harmless and innocuously apolitical — the eternal rebellion of youth against the intolerance of parents. Anne (Elise Caron), the 17-year-old middle-class heroine, runs away from home because her mother doesn’t approve of Frédéric (Philippe Lebas), her working-class boyfriend. En route to Israel to join a kibbutz, she is shortly joined by Frédéric and his pal Bruno (François Cluzet, who appropriately resembles Dustin Hoffman).

In Venice, where Anne’s about to leave on a boat, they hear about the demonstrations and tear gas in Paris, and shortly afterward a local politico named Anna-Maria who won’t put out for Bruno skips with his car and most of their belongings. Thus stranded, they gradually hitch their way back to Paris across a semi- immobilized France. Perhaps the most ideologically crucial dialogue occurs between Frédéric and Anne. He: “So we’ll miss the barricades, who cares?” She: “I think I’m pregnant.” The whole film can be summed up in that exchange.

“They wanted us to believe it was over,” declares the film’s concluding title, written out on the screen like a cheerful bill of lading. “For us it was only beginning.” Just about everything preceding this title is a glib guarantee that we never even begin to ask ourselves what “they” or “it” refer to.

The referent of “us,” alas, is all too clear. It’s that same team of shining, innocent hearts, all beating in sync, that thrilled to the radicalism of The Graduate and quickened to the subversive quavers of An Unmarried Woman (which, for my money, is no better or worse than Willie and Phil, just as, existentially speaking, Stardust Memories isn’t all that different from Manhattan).

Not having seen Kurys’ popular previous autobiographical feature, Peppermint Soda, to which this film is the sequel and spinoff, I can’t really comment on whether the gooeyness here has any real precedent. Either way, as a sentimental means of depriving May ’68 of any remaining political significance whatsoever — complete with an affecting cameo by Marco Perrin as a state trooper giving a flic’s account of the Paris events — Cocktail Molotov is clearly just what the bourgeois doctor ordered.

***

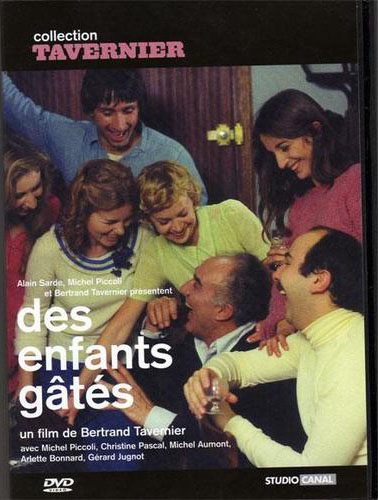

April 9: On Spoiled Children (Des Enfants Gâtés, 1977) — the fourth feature of former film critic Bertrand Tavernier, running through Sunday at the Public — I find it hard to do much than draw a polite blank. Set in a Praisian high-rise (in the 15th arrondissement, I think) that’s even uglier and more decrepit than the suburban ones in Godard’s 2 or 3 Things I Know About Her, the film is mainly concerned with what happens when the tenants band together to protest unfair landlord practices.

All this is laudable and not exactly boring, but it’s five days later when I’m writing this, and I’m hard put to summon up a plethora of details. Tavernier may be as steeped in 50s Hollywood as Peter Bogdanovich — his earlier Le Juge et l’assassin (1976) struck me at the time as an offshoot of 50s Preminger — and Spoiled Children often seems the epitome of a 50s Hollywood liberal film (a genre perhaps represented at its best by the 1960 Wild River), with the same sort of low-key realism.

Even the conventionally unconventional couple composed of the equally attractive Michel Piccoli (a 46-year-old filmmaker who’s moved away from his family to thrash out a script) and Christine Pascal (a student who lures him into the tenant organization) seems to exude the certainties of that era, overlaid by a soupçon of 60s license (e.g., Piccoli fully clothed beside a nude Pascal — an image out of Contempt). And to make the loose structure even looser, Piccoli’s wife’s work as a teacher of disturbed kids is also threaded through the patchy plot.

***

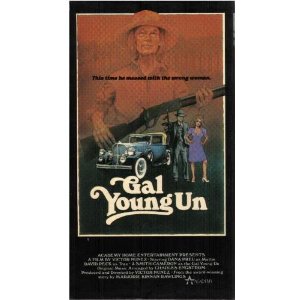

April 14: Victor Nunez’s Gal Young Un — on at the Art through next Tuesday, in First Run Feature’s ongoing festival of American independent films — is a small gem that’s probably worth 105 minutes of anyone’s time. Set in the backwoods of central Florida during Prohibition, it tells the story of a well-off widow (Dana Preu) who marries and gets exploited by a slick, young moonshiner (David Peck) who eventually brings home a teenage mistress (J. Smith, the title waif), until poetic comeuppance finally gets delivered. Sensually perfect in certain details — light falling on trees, a rock plunked into water — the movie pursues its witty, nondidactic feminist plot with a precise sense of period and place that puts a Kurys (or a Bob Rafelson) to shame.

Key lines of dialogue (or, just as often, the widow’s terse monologues) neatly lock into predestined slots with all the satisfying rightness of an old-timer snapping back a suspender strap — the kind of polished epiphanies that short stories tend to be built around. And because this film is adapted from a Marjorie Kinnnan Rawlings story of the same title, there’s a certain slowness in the pacing of the last laps that seems inevitable in most adaptations of short stories into features — the kind where you’re waiting a little for each gear change and plot point in the overall structure to click into place. But Nunez usually brings it off with honors because it can be regarded as a kind of country patience, too — the sort of dogged temperament that doesn’t mind slowing down some if it’s needed to get things right.

Gal Young Un gets things right. (The title, by the way, is a somewhat rarefied expression that, according to Nunez, can be traced back only to Florida in the 30s.) Dana Preu — an extraordinary nonprofessional who teaches English Lit., and reportedly derived part of her performance from memories of rural Mississippi in the 30s — has the kind of astonishing face that can walk away with a movie (although, move for move, she is equaled by a wonderful ginger cat — a central character, quite pivotal throughout — that can act up a storm himself.) At certain uncanny junctures, her country gestures, pauses, and intonations become poetic commentaries on Mattie Siles rather than the character herself — as deeply and pleasurably textured, in a way, as Nunez’s camerawork.

***

P.S. Some afterthoughts about Jerry Lewis’ Hardly Working to add to my comments of two weeks ago:

(1) The movie seems profoundly Jewish — in its relations to food (a wonderful, excruciating donut-sampling scene in Stone’s office) and to victimization, its Florida locations, its sexism, its playful sense of fantasy.

(2) As Jackie Raynal recently pointed out to me, it is made for kids and housewives — thanks to whom, one should add, the film is currently racking up at the boxoffice, despite widespread critical hostility and indifference. (In fact, it’s the current front runner in Variety‘s weekly list of the 50 top-grossing films.)

(3) The infantile terror and anguish conveyed by Lewis in certain scenes, at certain asocial moments (not all of them funny), is sharply evoked by Piccoli’s description of a Laurel and Hardy gag in Spoiled Children, in which Ollie asks Stan, “Which do you like better, me or apple pie?” and Stan, after looking back and forth repeatedly at Ollie and then at the audience, finally bursts into tears. Food, love, and mortality, all in a nutshell.