From the Chicago Reader (October 28, 1994). Thirty years later, it’s hard to decide whether this stinker is as bad as Beatty’s Rules Don’t Apply or perhaps even worse. That some of the ads for Love Affair renamed it Perfect Love Affair sounds to me like an act of desperation. — J.R.

* LOVE AFFAIR

(Has redeeming facet)

Directed by Glenn Gordon Caron

Written by Robert Towne and Warren Beatty

With Beatty, Annette Bening, Katharine Hepburn, Garry Shandling, Chloe Webb, Pierce Brosnan, and Kate Capshaw.

The writing and directing credits for Love Affair are legally correct but historically, aesthetically, and ethically wrong. A more accurate account of where the movie comes from, in terms of characters, plot, dialogue, and even camera placement, would have to cite the story written by Leo McCarey and Mildred Cram for Charles Boyer and Irene Dunne, inspired by an extended trip McCarey and his wife took to Europe. According to McCarey, seeing the Statue of Liberty slide into view as the ship approached the New York harbor gave birth to the plot: a man and a woman, each engaged to someone else, meet on such a liner, bound for Europe from New York, and fall in love. On their way back they make a date to meet at the top of the Empire State Building six months hence if they’ve both been able to shake loose from their commitments and if the man, a wealthy playboy who’s never held a job in his life, has been able to find work and thus make himself worthy.

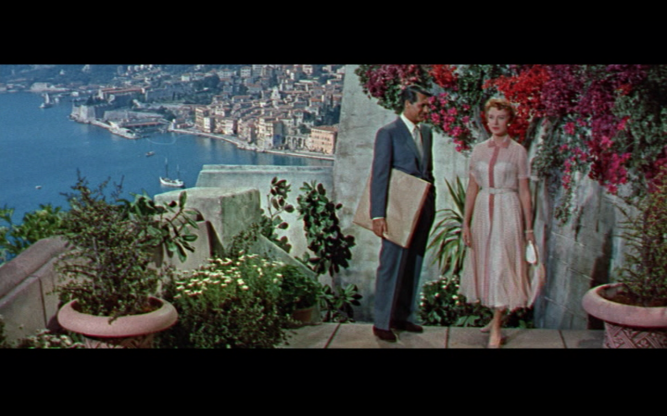

Out of this kernel came a screenplay by Delmer Daves and Donald Ogden Stewart, with additional input and last-minute rewriting by Daves and director McCarey, and a masterpiece among tearjerkers, the 1939 Love Affair. Further changes were made 18 years later, when McCarey did a remake with Cary Grant and Deborah Kerr called An Affair to Remember; 37 years after that, Warren Beatty hired Robert Towne to assist him in writing a remake starring himself and his wife, Annette Bening.

As for the directing credit, one has to bear in mind that, since Beatty is both producer and star, he was the one in control, and this is his final cut. The nominal director, Glenn Gordon Caron — a TV veteran whose previous features are Clean and Sober and Wilder Napalm — has a cut of his own that isn’t being released. The release version (and apparently Caron’s too) closely matches both McCarey originals not only in terms of scenes and dialogue but also in terms of mise en scene, including even certain camera placements and movements. So it’s highly questionable whether, auteuristically speaking, the 1994 Love Affair can be said to have any director at all.

When McCarey was asked toward the end of his life which of his two versions he preferred, he opted unequivocally for the first, a wise choice. Here he told the whole story in a brisk and tidy 87 minutes, whereas An Affair to Remember, the better-known version, is nearly half an hour longer. Each version reflects the fashion of its time. The sprawling languor of most 50s CinemaScope pictures has a lot to do with showing off production values and filling out the wide rectangular frame (an effort lost on viewers seeing the film on TV today, unless they come across a letterboxed version on cable or laser disc). Part of the difference can be explained too by Grant’s desire to give his role more comic detail, which means that more time is spent clowning around — although paradoxically the second version ends only with tears, while the first ends with tears and laughter, perhaps because there was generally more snap, crackle, and irreverence in 30s movies.

Still, for all the excesses and other weaknesses of the 1957 movie (and there are plenty), it is the one that reduces me to jelly at its key moments — perhaps because it’s the version I saw first, the one made in my own era. For the same reason, I might well be underestimating the possible effect of the Beatty version on someone who hasn’t seen the previous two, though it’s hard to believe this movie could register with the same impact.

Speaking recently to the Chicago Tribune‘s Michael Wilmington, Beatty essentially defended his decision to offer a second remake by comparing himself to a concert singer selecting a popular repertory item to perform. “You sing a concert for Wagnerian stuff, Italian grand opera, and you do German lieder,” he said. “And then, at a certain point, you sing ‘Melancholy Baby’ or ‘Danny Boy.'” Setting aside the question of what the equivalents to Wagner, Italian grand opera, and German lieder are in Beatty’s previous oeuvre, what is most telling about his analogy is the assumption that certain classic movies, like certain classic tunes, can be appropriated, detached from their original makers and performers.

Beatty has already appropriated one classic film title, Heaven Can Wait — belonging first to one of Ernst Lubitsch’s loveliest late works (1943) — for his remake of the less-than-classic Here Comes Mr. Jordan 16 years ago. But this time he’s going after bigger game. Apart from the issue of his success or failure, it’s fascinating to see what some of the changed details tell us about the differences between 1939, 1957, and the present — as well as the differences between McCarey and Beatty.

All three versions begin with news reports about the recent engagement of the playboy hero. In 1939 these are radio broadcasts in the United States, France, and England; in 1957 they’re TV broadcasts in the United States, Italy, and England (beginning with Robert Q. Lewis, a familiar TV presence in that period, and ending with a repetition of a gag from 1939 involving a bemused British announcer); and in 1994 they’re all videotape replays of news reports on various American TV shows, beginning with Entertainment Tonight, being watched and commented on by the hero’s manager cum personal assistant (Garry Shandling). And the hero needs a manager/assistant in Beatty’s version because he’s no longer gainfully unemployed; here he’s a former football star working as a TV sportscaster. This time, in short, the only news that matters is American news, and the comedy is transposed from the news reports themselves to their evaluation as sound bites.

Now that the hero is a playboy with a job, his need to find a vocation after he falls in love must be defined differently. In McCarey’s mawkish conception, he becomes a serious artist, which entails living in a garret and working as a billboard painter until he finally sells his first canvas — an improbable but necessary solution because one of his paintings figures centrally in the film’s climax. Beatty’s hero is a hobbyist painter, which makes the same climax possible, but finding a new vocation means giving up his TV job to coach football at an obscure east-coast college. This means he has to check into more modest quarters — hardly a garret — at the plush Essex House whenever he comes to New York.

Much more consequential than these changes are the ones involving transportation and religion. A luxury ocean-liner cruise from New York to Europe no longer seems as plausible, so Beatty and Towne substitute a first-class flight from New York to Sydney, Australia, that becomes grounded in the South Seas, where the hero and heroine board a Russian ship. A pivotal meeting with the hero’s grandmother in Europe in the earlier versions (beautifully played first by Maria Ouspenskaya and then by Cathleen Nesbitt) now becomes a star turn for Katharine Hepburn, coaxed out of retirement to play the hero’s aunt in Tahiti.

In both McCarey versions, the grandmother has a private chapel where the hero and heroine go together to pray. It’s easy to see why Beatty — who isn’t a practicing Catholic, as McCarey was — decided to delete this scene, but I think it can be argued that everything that follows, in both this sequence and the remainder of the film, feels different and means less because of this omission.

For McCarey, this scene is the turning point of the story, for emotionally complex reasons. The hero is anything but devout, but the sight of Terry McKay (the name of the heroine in all three versions) praying devoutly beside him opens up a new world of possibilities — a world of faithfulness, devotion, marriage, and children — that he struggles to achieve for the remainder of the movie. His own discomfort and embarrassment in the chapel, which McCarey exploits semicomically, is a key ingredient in both the 1939 and 1957 scenes; in both, after Terry crosses herself, the hero does the same but then awkwardly dovetails the gesture into straightening his tie. It’s a beautiful, fleeting moment that for me defines the essence of McCarey’s genius, helping to explain why Jean Renoir once remarked that McCarey understood people better than anyone else in Hollywood.

Lacking a religious context for the lovers, Beatty needs some sentimental equivalent, and what he relies on, ultimately, is star auras. Implicitly and explicitly, he cues the audience by means of his own reputation as a former ladies’ man, Bening’s reputation as the woman who inspired him to settle down and have children, and Hepburn’s reputation as a freethinker who’s lived a long, illustrious life. (The self-referentiality extends to other details as well: making the hero a former football star obviously refers back to Beatty’s lead part in Heaven Can Wait, as well as to his brief stint in college football.) It’s a substitution that can work for viewers only if they regard movie stardom with the same hushed awe that McCarey inspired in relation to religious faith.

Then there’s the issue of whether Beatty is a viable equivalent to Boyer and Grant. In my view, he’s fighting a losing battle — though Bening is adept as Terry. Indeed, I think it could be argued that not once in the history of movies has a masterpiece resulted when a movie’s star retained final cut without being the director. And one can cite cases, like Swing Shift and The Natural, when that setup has had ruinous effects. As for remakes, it stands to reason that if you try to redo a work of art without the original artist, you’re bound to damage the artistry as well.