From the Chicago Reader (June 2, 2000).

On October 5, 2014, I had the pleasure of introducing The Sandwich Man at the Museum of the Moving Image’s exhaustive Hou retrospective in Astoria. My late friend Gilberto Perez came to the screening and we had dinner afterwards; it was the last time I ever saw him.

For a Turkish translation of this article, go here. — J.R.

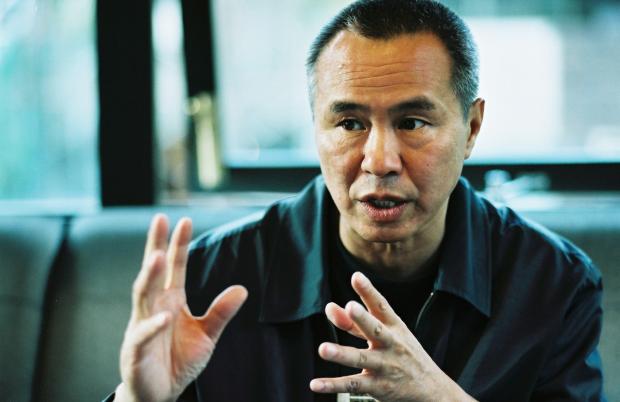

Films by Hou Hsiao-hsien

By Jonathan Rosenbaum

We are what we pretend to be, so we must be careful about what we pretend to be. — Kurt Vonnegut Jr., Mother Night

How significant is it that neither of the two greatest working narrative filmmakers is fluent in English? Not very. But it might be logical. After all, most of the people in the world, including those in Iran and Taiwan, don’t speak English, even though that places them, in American eyes, in the margins, outside even the on-line global culture.

If being in the margins means being in the majority, it stands to reason that Abbas Kiarostami and Hou Hsiao-hsien, as chroniclers of what’s happening on the planet at the moment, should both be poet laureates of the sticks — though they don’t have much in common beyond a taste for filming in long shot, pioneering direct sound recording in their national cinemas (in both cases to honor the speech patterns of nonprofessional actors), and a general sense of philosophical detachment. It’s no wonder that they respond to each other’s movies so well, even though publications like Vanity Fair and the New Yorker pretend they don’t exist. Both men come from cultures currently undergoing cataclysmic change, for the better, which may be part of what was acknowleged in the prizes recently awarded at Cannes: the grand prize went to a mainland Chinese feature, the best male performance went to a Hong Kong actor, the best director went to Edward Yang (Hou’s only peer in Taiwan), the jury prize was shared by Samira Makhmalbaf, and the Camera D’or went to two other Iranian directors. As usual, U.S. journalists panicked because Hollywood studios weren’t calling the shots — a sure sign that world cinema is still alive and kicking: bad news for Jack Valenti, but great news for global citizens everywhere — especially those who realize that democratic reforms in Taiwan and Iran don’t have to follow an American model.

One thing that was so cheering about the touring retrospective of Robert Bresson — which played to packed houses around the world in 1998 and 1999, shortly before his death — is how fully it reversed 40 years of received wisdom about his work, which was dismissed as terminally esoteric and pretentious. Pauline Kael, Dwight Macdonald, John Simon, and many other mainstream reviewers had dismissed it at least since Pickpocket, viewing it as proof of how perverse and life denying Gallic notions of art could be, and Orson Welles — who seemed temperamentally incapable of supporting any film director who dissed actors, whatever the reason — headed the contingent of filmmakers who regarded Bresson’s work with scorn. But the premise that Bresson was too rarified fell away as soon as audiences had a proper chance to see his films in good prints.

Something similar has been happening with Hou Hsiao-hsien (pronounced “Ho-shao-shen”) ever since a traveling retrospective of his own work premiered in New York last fall. The success of the program was even more dramatic because virtually none of Hou’s features has ever had a commercial run in the U.S., all of them having been deemed too difficult by distributors — at least until WinStar Cinema, in one fell swoop, picked up distribution rights to half of them. Over the next three weeks, the Film Center is showing all seven of these treasures in new 35-millimeter prints and presenting the only North American print, in 16-millimeter, of another one, A Summer at Grandpa’s (1984) (showing for free on Tuesday, June 20, shortly before the series concludes).

This is certainly a windfall. A half dozen Hou films, most of them relatively minor, are missing — his first five, made between 1980 and 1983, and his ninth, Daughter of the Nile (1987) — because of problems getting the rights to show them. (The same problem ruled out Olivier Assayas’s documentary on Hou, HHH.) Ironically, the uncharacteristic Daughter of the Nile is the only Hou film that has had a U.S. run, though it came and went so fast this hardly counts.

I’ve seen Hou’s third and fourth films, and I want to discuss them both briefly because of the light they shed on the others. Green Green Grass of Home (1982) — by all accounts like its predecessors, Cute Girl and Cheerful Wind — is a lightweight, technically assured, commercially successful feature in ‘Scope starring pop star Kenny Bee (this time as a substitute schoolteacher). It has bouncy musical interludes and lots of zooms and pans, and seems written and directed by someone who doesn’t consider himself an artist. Its most serious element is some ecological preachiness against electrocuting fish in a village stream, and it anticipates Hou’s later work in only a few glancing ways: a graceful handling of kids, adeptness at filming in long shot, and a taste for musical repetition in its title (a taste also apparent in A Time to Live and a Time to Die, Good Men, Good Women, Goodbye South, Goodbye, and even Dust in the Wind, whose original title translates as “Love, Love, Wind, Dust”).

Paradoxically, Hou started to become an artist when he began to hire screenwriters, almost exclusively novelist Chu Tien-wen but also actor (and more recently filmmaker) Wu Nien-jen. Wu adapted the short story used in “Son’s Big Doll,” Hou’s perfectly formed 33-minute segment for The Sandwich Man (1983), a three-part sketch feature generally regarded as the first film of the Taiwanese new wave.

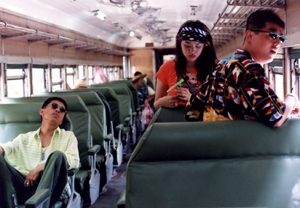

The difference in style between Hou as an entertainer and Hou as a maker of art movies — even in a country whose art cinema has been partly financed by gangsters — is radical. Yet bridging the two are populist attitudes that complicate his art-house elitism, yielding an ambiguous cultural blend that Westerners seem to find hard to place. (It’s worth adding that Hou dreamed of becoming a pop singer and a film actor before he turned to directing, abandoning the first ambition after an attack of stage fright and the second after deciding he was too short.) For all the differences between the relatively conventional narrative style of Dust in the Wind and the exploration of everyday states of being in Goodbye South, Goodbye, the two films begin almost identically with exhilarating point-of-view shots of trains moving through green landscapes, followed by shots of jostling passengers inside — a painterly sense of fluctuating light modeling their features as the trains emerge from tunnels. It’s also worth remarking that City of Sadness, one of Hou’s more difficult films for Westerners in terms of plot, was his biggest hit in Taiwan; by broaching historical and cultural issues that couldn’t be discussed when the island was under martial law — that is, for the entire century until 1987 — it caused a major sensation.

Assayas describes Hou’s paradoxical personality well in his preface to a recent French collection about him. He recounts meeting Hou in Taipei as a film critic in 1984 and again for his recent documentary: “His manner of slipping from grown-up rationality to childish laughter is intact, as is his way of moving between intellectuals and small-time mafiosis in a sort of studied uncertainty, hazy with grass, alcohol, or bin-lan (a plant-based kind of speed). But here where only instinct matters, theory and philosophy assume a growing importance; and it isn’t simply a matter of a notion about perception — generally interesting only to filmmakers — but also the classical Chinese tradition, with the gravity and intensity peculiar to autodidacts.”

Hou’s shift from entertainer to artist also suggests an ambiguity in cultural identity, traced symbolically by the hero of his Chekhovian sketch for The Sandwich Man. A young newly wed father makes himself up as a clown with a sandwich board to advertise a local movie theater. When this humiliating getup doesn’t attract customers he’s allowed to pedal around a cart promoting the new movies instead, but he then discovers that his baby son doesn’t recognize him without the clown makeup.

In retrospect, this story could be read as a parable about the existential dilemma of being Taiwanese. Hou was born in Canton on April 9, 1947 — shortly after the end of the Japanese occupation, in the midst of the civil war between communists and nationalists — and wound up with his family in Taiwan the following year. Quite typically, they expected this move to be only temporary. (This story is recounted in A Time to Live and a Time to Die, his most directly autobiographical film.) Such miscalculations, and the profound confusion about identity they engender, are at the root of Hou’s mature filmmaking — along with uncertainty about how much of Taiwan is Chinese and how much is aboriginal, Japanese, or American. Such concerns also imbue the childhood memories of Hou’s screenwriters (in A Summer at Grandpa’s and Dust in the Wind) and the overall history of Taiwan in the 20th century (the subject of Hou’s magisterial trilogy — City of Sadness, The Puppet Master, and Good Men, Good Women — and of his attempt to deal with the present using a small-time hood and his entourage, Goodbye South, Goodbye).

The only title in the retrospective I haven’t noted is Flowers of Shanghai (1998), Hou’s latest, based on a novel published in 1894 and set exclusively inside Shanghai brothels — a remarkable effort that some critics consider his best work. I admire it a great deal, but I also find it somewhat intractable — if only because I can’t read it through the critical grids outlined above.

In more ways than one, Hou has become the most experimental of major contemporary Asian filmmakers, at least since City of Sadness (1989), and part of what makes his work so breathtaking is that he never does the same thing twice. In this respect, he seems comparable to William Faulkner in the 1920s and 30s — another formal innovator dealing with the history and indigenous existential dilemmas of his own remote neck of the woods. Goodbye South, Goodbye, with its jaundiced view of modernity, reminds me in some ways of Sanctuary, and the contrapuntal Good Men, Good Women recalls elements in The Wild Palms; even my favorite Hou feature, The Puppet Master [see above], resembles my favorite Faulkner novel, Light in August, as a story about seeking or accepting one’s own identity. (My other favorites are Son’s Big Doll, A Time to Live and a Time to Die, and City of Sadness. I haven’t yet seen Hou’s own favorite, the 1983 The Boys From Fengkuei — another item missing from the retrospective.)

I haven’t done more here than scratch the surface of these bottomless movies. For instance, I haven’t said a thing about the opposition of city and country in so many of Hou’s pictures; the city, almost invariably a carrier of cultural viruses, is what the characters need to escape from — the city-based mother in A Summer at Grandpa’s is literally ailing when her kids escape to the hinterlands. Or about Hou’s virtuosic uses of long takes (as in the jaw-dropping opening shot of Flowers of Shanghai), his colors and lighting and deep focus, his profound sense of place. Or the carefully delayed exposition in The Puppet Master — based on the memories of the late Li Tien-lu, whose presence as an actor in Dust in the Wind and City of Sadness and as himself in The Puppet Master, dialectically posed against his fictionalized younger selves, is unforgettable. Or the stretches of airy and speedy motion by train, motorbike, and car that alternate with patches of aimless drift in Goodbye South, Goodbye. Or how certain exquisite uses of a deaf-mute still photographer in City of Sadness (including intertitles for his written messages) and a barmaid putting on makeup at a dressing table in Good Men, Good Women become gateways into the limitless reaches of the cosmos, brimming with infinite possibilities. For Hou’s movies are about the glory and terror of becoming, and there are few more potent subjects.