From Monthly Film Bulletin, December 1976 (Vol. 43, No. 515). I was present when the late Andi Engel, the film’s English distributor, decided to give the film an English title that was less sexist than Utamaro and His Five Women. — J.R.

Utamaro O Meguru Gonin No Onna (Five Women Around Utamaro)

Japan, 1946

Director: Kenji Mizoguchi

Dist–Artificial Eye. p.c–Shochiku. p. manager–Toyokazu Murata. sc–Yoshikata Yoda. Based on the novel by Kanji Kunieda. ph–Shigeto Miki. ed–Sintaro Myamoto. a.d–Isamu Motoki. m–Hiseto Osawa, Tamezo Mochizuki. sd. rec–Hisashi Kase.historical adviser–Sonao Kahi. l.p–Minosuke Bando (Kitagama (Utamaro), Kotaro Bando (Seinosuke Koîde), Tanaka Kinuyo (Okita), Kowasaki Hiroko (Oran), Izuka Toshiko (Dayu Tagasode), Kinnosuke Takamatsu (Juzaburo), Shotaru Nakamura (Shizaburo), Minsei Tomimoto (Takemoro), Katsuhisa Yamaguchi (Kisuke), Aitzo Tamasuma (Sobe), Eiko Ohara (Yukie Kano), Kyoko Kusajima (Oman), Kimiko Shirotae (Oshin), Junko Kajami (Maid in Kano Family), Mitsuei Takegawa (Tayu Karauta), Kimie Kawikami (Matsunami), Aiko Irikawa (Shodayu), Junnosuke Hayama, Masao Hori. 3,399 ft. 94 mins. (16 mm.). Subtitles.

Tokyo in the late eighteenth century. Seinosuke Koide, a student at the Kano Art School, is enraged when he discovers in a print shop that the artist Utamaro has written on one of his own prints that even his rough sketchesare “full of life”. Feeling that his teacher Kano has been insulted, he rushes to the house of Okita, one of Utamaro’s models, and challenges Utamaro to a duel. Insisting that they ‘duel’ with brushes, Utamaro quickly demonstrates hissuperiority by improving on one of Koide’s female portraits, and then proceeds to the house .of courtesan Dayu Tagasode, drawing a picture on her back at the request of her tattooer. Later, Tagasode runs off with Okita’s lover Shizaburo; and Koide, who has broken off his engagement with his teacher’s daughter Yukie and become Utamaro’s disciple, begins an affair with Okita. After quarrelling with Okita on Yukie’s behalf, Utamaro grows depressed and his work suflers. With the connivance of his servant Take and others, he is persuaded to peek at a group of women fishing semi-nude at the whim of an eccentric Lord, and is immediately taken with Oran, a commoner’s daughter whom he persuades to pose for him. When some of his prints offend the Tokugawa government, Utamaro is arrested and his hands are subsequently bound for fifty days to keep him from drawing.

Koide meanwhile flees with Oran, and Okita goes looking for Shizaboro. Koide writes to Utamaro requesting money, and Yukie and Take — who has just announced his engagement to Oshin, another model of Utamaro’s — take the money to him; but Yukie is heartbroken when she finds him living with Oran. After finding Shizaburo and Tagasode, Okita tries unsuccessfully to take her former lover back with her; she then stabs both of them to death and returns to Utamaro — defending her act as a refusal to compromise her passion that is equal to Utamaro’s commitment to his drawings — before giving herself up. Utamaro’s sentence comes to an end and his hands are unbound; sake is brought out, but he insists on returning to his drawing immediately.

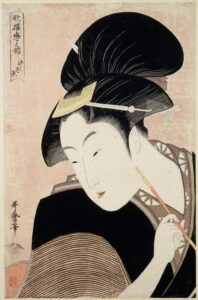

Apparently not very much is known today about the life of Kitagama Utamaro (1753-1806), the earliest of the great masters of the ukiyo-e school, whose colour prints were among the first from Japan to become familiar in the West. For Mizoguchi to make a film about him at all in 1946, under the vigilant eye of Douglas MacArthur’s Occupation forces, was no easy matter: jidai-geki (period films) were officially outlawed because of their ‘feudal’ and ‘undemocratic’ aspects, and it appears that Mizoguchi had to argue at some length that Utamaro was a “man of the people”, and that the film would take a modern look at the rights of women, before he could embark on the project at all. Eight years later, he complained about not having had enough time to work on the film and having had to consult the Occupation Authorities at every stage of the proceedings. Yoshikata Yoda, the scriptwriter, has further noted that the contrasting liberalism of the Occupation’s censor board regarding erotic scenes also gave some impetus to the project, adding that his own thoughts about Utamaro were “complex” and “muddled” and that “this is probably the reason for the confusion and dispersion of [the film’s] theme”. For what he had in mind, “almost unconsciously”, was to create a partial portrait of Mizoguchi himself through the depiction of Utamaro — a parallel which remains evident on many levels. Commonly regarded as a minor work, Five Women Around Utamaro — which is known under the rather misleading and offensive title Utamaro and His Five Women in the U.S. — offers, in fact, a highly complex reflection on the director’s art. While several viewings would probably be needed in order to determine whether it belongs with his highly distantiated masterpieces of the late Thirties and early Forties (The Sisters of the Gion, The Story of the Late Chrysanthemums, The 47 Ronin), or might more properly be regarded as an ambitious failure with an expressive intensity comparable to Montparnasse 19 or A King in New York (two other examples of rebellious art born out of adversity), it clearly cannot be dismissed as an indifferent work. The immediate difficulties that it presents to the viewer — a plot eschewing any easy identification thanks to a virtual absence of close-ups, a large cast of characters and a periodic displacement of narrative centres — are not at all unrelated to its achievements. Significantly, the artistry of Utamaro is presented more as a postulate than as a visible fact, and it is only in the final shot — when an overlapping catalogue of his work is literally thrown into view — that one is permitted to experience it directly at any length; prior to this, one mainly has to assume it through historical hearsay, and through the importance that it takes on for other characters.

But the abstract nature of his status perfectly matches the film’s subject, which finally has less to do with art itself than with the conditions and consequences of its place within society. Shown as a revered and controversial but far from purely heroic figure, Utamaro is an elusive character whose significance principally rests upon the identity and importance he confers upon others — above all, his disciple Koide and his models. The distance traversed from Oran’s shy modesty when she first poses for the artist, hiding her face in embarrassment, to the unmistakable vanity she displays upon confronting Yukie, after she has film throughout. It is scarcely coincidental that Tagasode runs away with Shizaburo just after Utamaro has graced her back with a ‘masterpiece’, or that Okita, the injured mistress of Shizaburo, is finally driven to murder in emulation of the artist’s own refusal to compromise, for these are the only ‘pure’ acts of defiance that these models are able to commit; their society permits them no ‘art’ of their own. Reduced to perfected images of themselves, they respond by taking on these ideal emblems as their identities: “Okita’s spirit has come to bid you farewell”, Okita announces in a daze as she returns from her crime, and soon afterwards she says: “After I die, please be kind to the woodcut print of Okita!” Not so much the guiding force of the film as the centre of a system of valuation in these terms, Utamaro is a master whose career is ultimately subject to the whim of his own ‘masters’ — forces that remain pointedly off-screen and hence no less ‘abstract’ than his own genius. (The precise reasons why his drawings offend the shogunate are never spelled out.)

Considering the nature of the film’s displacements, it is not surprising that many of the moments of greatest beauty and power take place in the margins of the story proper: the opening track past a formal procession of anonymous characters, with parasols and cherry blossoms marking the camera’s path in a delineation of sheer pictorial splendour; the astonishing image of Okita, during her search for Shizaburo, crossing a bridge and glancing at a peasant emptying water from a boat; and even the climactic scene of Okita’s confession, after she flees from the frame and the camera remains fixed on the empty wall while other women rush past — before moving aside to pick up — Utamaro himself, at once impotent and triumphant as he declares, “I want to draw so much !” When his hands are finally unbound in the last scene, the artist resumes work, sitting in the foreground, facing the camera: Mizoguchi’s own return to cinema after his country’s defeat is no less ambiguous.