From The Soho News (February 25, 1981). One can trace some updates on my thoughts about Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One over 17 years later and Killer of Sheep over 26 years later by following the links provided here. — J.R.

Feb. 16: A double feature of two class-conscious films directed by Carol Reed , The Stars Look Down (1939) and Kipps (1940), at Theater 80 — my first look at either movie. Trying to arrive at a plausible reverse-angle for the first movie — that is, a precise sense of its audience and context in early 1940, when Graham Greene wrote for The Spectator, “Dr. Cronin’s mining novel has made a very good film — I doubt whether in England we have ever produced a better” — I find myself hopelessly hamstrung, stuck in a narrow sort of timewarp called the present.

The problem is, I can only come up with a romantic, movie version of an English movie audience three years before I was born, a Thomas Pynchon fantasy à la Gravity’s Rainbow (whose sexy, existential London is itself very much a pungent blend of remembered movies from that period). Admittedly, Greene’s oddly familial use of first person plural tells me a little something, too. (Can one imagine a contemporary American critic writing that Apocalypse Now or Close Encounters of the Third Kind “is a very good film — I doubt whether in America we could have produced a better”? But when it comes to reinventing or imagining the social impact of this movie 41 years after the fact, I might just as well be flirting with ghosts.

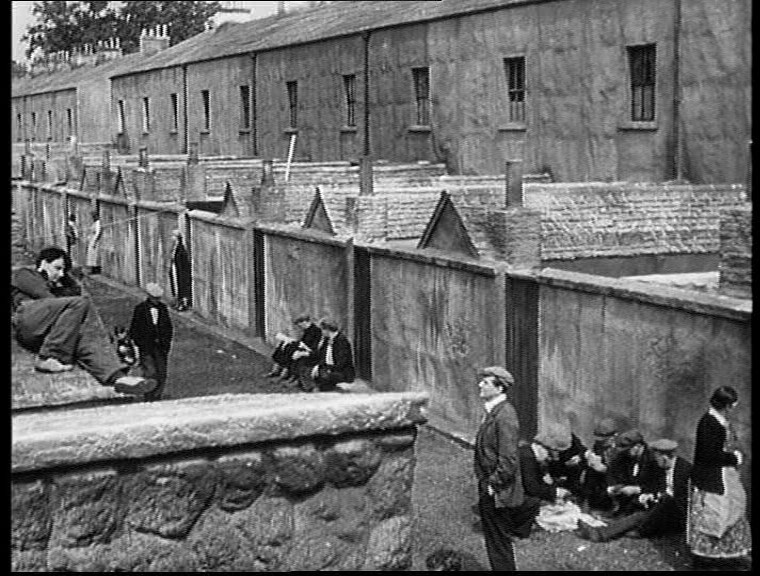

Filmically, I find that I largely respond to The Stars Look Down in relation to other periods: the futurist Grand National logo with its giant clock takes me back to Metropolis (1927), the opening sequence with arriving workers evokes Renoir’s 1935 Toni, while the editing throughout, as in Reed’s 1947 Odd Man Out, has some of the headlong syncopated drive of the silent Soviets (as well as some of the latter’s endless fascination with industrial smoke).

When it comes to the didactic parts, my favorite bit of dialogue is a parody of non-utilitarian educational theory out of Dickens’ Hard Times or the Chinese film Breaking with Old Ideas. When young Michael Redgrave protests to a schoolmaster superior that comparing the shape of Scandinavia to the shape of a bear is meaningless to boys who’ve never seen a bear, the confident reply is, “We teach these boys two things at once — the shape of Scandinavia and the shape of a bear.” Another version, in short, of what The Stars Look Down is (and isn’t) teaching me.

Kipps, more immediately charismatic, also seems more legibly contemporary by having been made around the same time as Citizen Kane. With the help of music-hall artist Arthur Riscoe (as Chitterlow) and giddy decor, there’s the same kind of relish for turn-of-the-century Victorian braggadocio and nostalgia, e.g., a montage of successive shop-window displays euphorically spelling out the passage from 1900 to 1905.

***

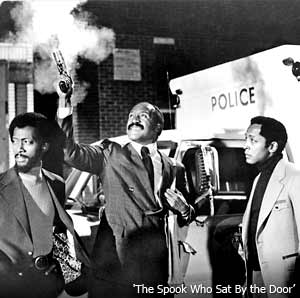

Feb. 17: A different historical problem, involving the more immediate past, rears its inglorious head at the press show I attend for the upcoming Retrospective of Black American Cinema, which will be at the Public Theater from Feb 27 through March 8. The feature in question is The Spook Who Sat By the Door (1973), co-adapted by Sam Greenlee from his novel, and directed by Ivan Dixon — a film whose description in Daniel J. Leab’s From Sambo to Superspade: The Black Experience in Motion Pictures is unfortunately limited to the fact that Variety called it “an `atypical blaxploitationer’ because it had `little gore but lotsa racist and revolutionary blather’ in developing a plot whose theme was that ‘anything violent goes — including mass murder — providing the victims are white.'”

Actually the premise of The Spook Who Sat By the Door is a good deal wittier than that. (Not to say more complex — in the final sequence, the black hero also kills his best friend, a black cop.) It calls to mind James Baldwin’s remark at the beginning of his analysis of Guess Who’s Coming To Dinner? (in his shamefully neglected The Devil Finds Work): “A black person can make nothing of this film — except, perhaps, Superfly….” The Spook, which nominally belongs to the same short-lived genre as Superfly, proceeds to show, more or less, what a black person can make of the CIA: adopt all its combat training and technological warfare skills, as its hero does, and then teach them to other black people in the slums, preparing them for armed revolt.

More powerful conceptually than it is in narrative or dramatic terms (the overall rhythm is choppy, and Herbie Hancock’s soundtrack score is a distinct disappointment), this movie still deserves a wider space in the history books for the sheer audacity and goofy logic of its revolutionary content. The plot’s elegant rhyme scheme in the first half, whereby each form of James Bondish CIA instruction gets transferred to the ghetto, reminds me of the John Bircher I once met who told me that his parents were Communists, and that one cell meeting was pretty much like another. According to Yann Lardeau in last month’s Cahiers du Cinéma — reporting on this retrospective of 40-odd black films when it showed in France last year — the film had an immediate success when it was released, but subsequently was withdrawn from circulation. I wonder why.

Some commentators would argue that the antiwhite racism of a movie like this — or, more precisely, the premise that all whites are racists — is “just as bad” as, say, the antiblack racism of The Birth of a Nation, or the anti-Oriental racism of The Deer Hunter. If and when an antiwhite movie is treated reverentially and respectfully in the national press, and cops a few Oscars to boot, I might be willing to concede the point….Meanwhile, for contrast, Ronald Gray’s 16mm black-and-white short, Transmagnifican Dam- bamuality: A Domestic Drama, judiciously crams into one crowded flat some thunderous family spats and a teenage boy’s skyrocketing energies (which eventually are channeled into playing a modal piano piece in Hancock’s prettiest Maiden Voyage style — in a tinny, disembodied soundtrack worthy of an early Kuchar Brothers opus).

***

Feb. 8: At another press show for the Public retrospective, I look at two more features that couldn’t be more different — either from the one I saw yesterday or each other. Indeed, if all these films — including Bill Gunn’s semi-impenetrable but original and intriguing Ganja and Hess (1970), which I saw at the Critics’ Week in Cannes in 1973 — seem to have a single trait in common, this is an obscure and/or anticommercial title. Today’s candidates clearly aren’t destined for many marquees: William Greaves’ Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One (1968) and Charles Burnett’s Killer of Sheep (1977).

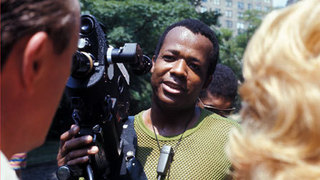

The first is a sort of bush-league version of Jacques Rivette’s epic L’Amour Fou; interestingly enough, it appears to have been shot around the same time, although the possibility of any transatlantic cross-influences — as with Kipps and Citizen Kane — seems pretty remote. Rivette’s approach was to film rehearsals of Racine’s Andromache both in 35mm and by a 16mm documentary crew, and to create a domestic fiction involving the director of the play and his (fictional) wife interacting with this material.

Take One, shot only in 35mm, uses polished split-screen techniques to show an ugly quarrel between a white middle-aged couple in Central Park, both as a fiction and as a fiction-being-filmed, often juxtaposing as many as three camera angles at once. This in turn is alternated with apparently extemporaneous reflections from the crew about just what producer-director-editor Greaves has in mind, which no one seems clear about. There’s a certain automatic fascination in this kind of game, similar to that in see-yourself-as-others-see-you TV monitors — only in this case, it’s see-yourself-watching-a-fiction-film. Unfortunately, as certain crew members point out, the fiction has no interest in its own right — dialogue and acting are uniformly bad — which gives the whole thing the feel of an academic exercise (quite unlike the galvanizing Rivette film).

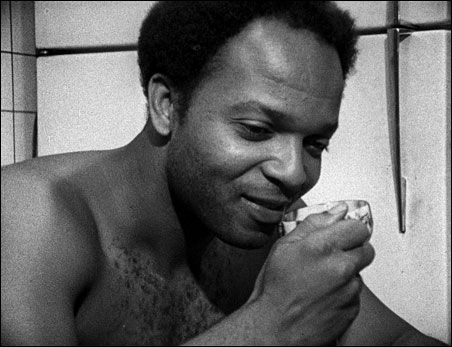

Killer of Sheep is something else entirely — perhaps the first really detailed and textured glimpse of everyday life in a black ghetto that any film has afforded me, in a stark set of poetic notations (in 16mm and black and white) that recall Bill Douglas’s autobiographical depiction of Scottish mining villages in My Childhood. Like Douglas, Burnett essentially works in vignettes, and the total effect in this case is closer to that of a tightly knit collection of stories than that of a novel.

A lot of this remarkable $10,000 feature is simply a matter of trying things out, and not everything works. Barring an inspired and exceptional use of Louis Armstrong’s West End Blues as an obligato one sequence, the varied eclectic uses of music are usually distracting and obtrusive, and the narrative development throughout is choppy. But the acting — most of it, apart from Henry Gayle Sanders in the title part, by nonprofessionals — is never less than incredible, and the densely conveyed sense of Watts in this film leaves a strong residue.

I suppose Killer of Sheep can be regarded as Italian neorealist to the same degree that, say, Raging Bull and The Elephant Man are German Expressionist. Comparing Burnett’s film to Rossellini in the 40s is like putting those boxoffice beasts alongside The Last Laugh and Faust in the 20s — for who are De Niro and Hurt but Emil Jannings recycled, and who are Scorsese and Lynch but butch versions of Murnau? That all three directors coexist in America in 1981 seems almost beside the point.