From the August 3, 2007 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

KILLER OF SHEEP ****

DIRECTED AND WRITTEN BY CHARLES BURNETT

WITH HENRY GAYLE SANDERS, KAYCEE MOORE, CHARLES BRACY, EUGENE CHERRY, JACK DRUMMOND, AND ANGELA BURNETT

WHEN Opens Fri 8/3

WHERE Music Box, 3733 N. Southport

INFO 773-871-6604

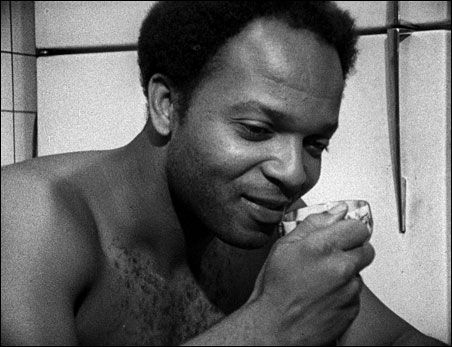

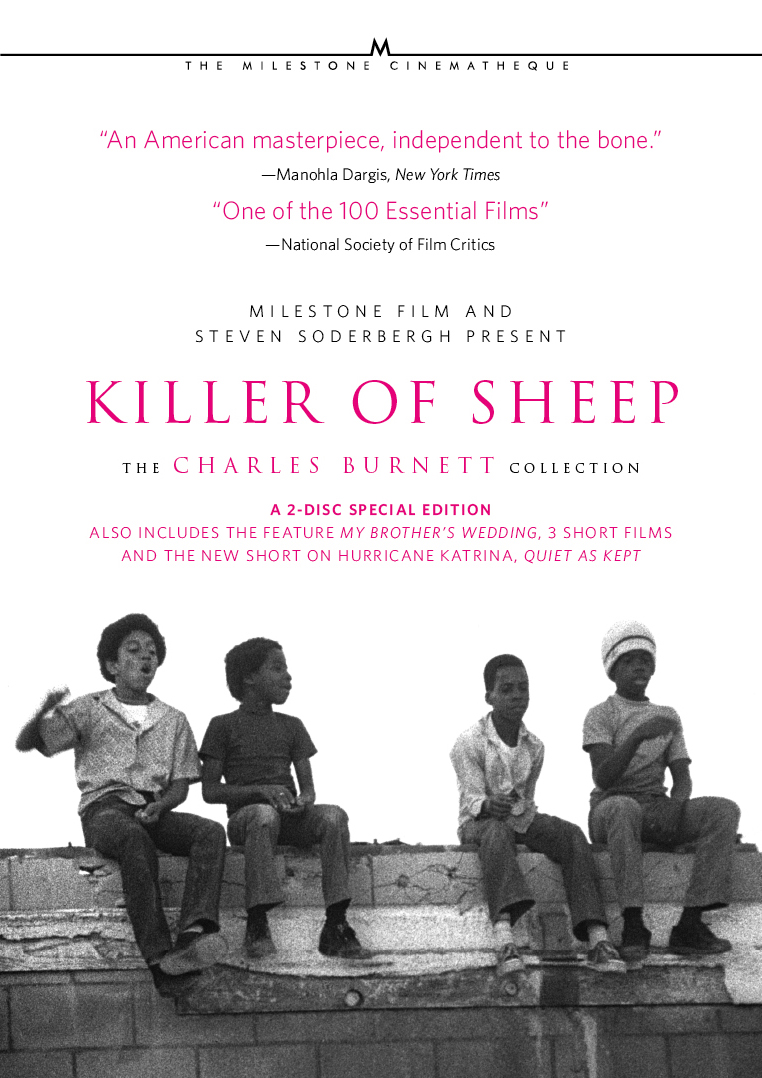

Thanks to the excellent restoration work of the UCLA Film and Television Archive and the patient heroism of Milestone Films’ Dennis Doros — who has spent years acquiring the music rights for a film largely built around pieces of music — Charles Burnett’s monumental first feature, Killer of Sheep (1977), is finally getting its first commercial release. Shot by Burnett himself in black-and-white 16-millimeter for less than $10,000 — as his master’s thesis at UCLA — this portrait of everyday life in Watts has steadily grown in resonance and reputation over the past 30 years. It’s centered on the melancholy off time of the title hero — a weary abattoir worker (the wonderful Henry Gayle Sanders) — with his family and friends. The slow burn and slow drip of this off time while he stews in his own juices is essential to the movie’s experience.

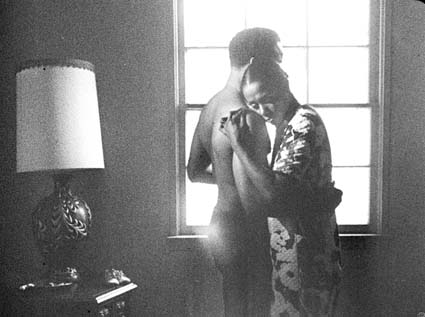

We also catch a few glimpses of the hero at his job, but most of what we know about his work and how he feels about it comes from seeing his general alienation and exhaustion when he’s at home: repairing the kitchen sink or laying out linoleum, sluggishly dancing with his wife in the living room, berating his son for addressing her in a “country” fashion as “dear,” refusing to participate in a robbery being planned by a couple of neighbors, or trying to fix a broken down car.

In 1990, Killer of Sheep was selected by the Library of Congress as one of the first 50 titles to enter the National Film Registry. And though it had a successful run in New York earlier this year, its approach to its subject is more lyrical and reflective than dynamic and dramatic, so it’ll never be a hit. People looking for action will probably be as turned off by it as Janet Maslin was when she panned it in the New York Times in 1978.

I reviewed it more favorably but still somewhat circumspectly for New York’s (long-vanished) Soho News in 1981, impressed mightily by both its overall depiction of ghetto life and its acting (almost entirely by nonprofessionals, apart from Sanders) but skeptical about its eclectic uses of music (classical, blues, R & B, and jazz), apart from “an inspired and exceptional use of Louis Armstrong’s ‘West End Blues’ as an obbligato to one sequence” toward the end. I think what I had some trouble adjusting to was the film’s stopping-and-starting rhythm and its form, a collection of vignettes. Today those same characteristics, combined with beautiful cinematography and an uncanny feeling for body language, seem key to the film’s power.

Charles Burnett’s name doesn’t show up in any of the 125 or so links to Web sites and major articles devoted to filmmakers listed on mastersofcinema.org. It’s not because Burnett hasn’t made many commercial movies, which can also be said of at least half the people on the list. I think it has more to do with Burnett’s resistance to hustling and branding, which is in fact an important part of his greatness. He certainly knows how to make movies — and all kinds of them, ranging from contemporary folktale (To Sleep With Anger, 1990) to police docudrama (The Glass Shield, 1994) to stirring period agitprop (the wonderful Nightjohn, made in 1996 for the Disney Channel) to provocative TV documentary employing fiction (Nat Turner: A Troublesome Property, 2003). But he appears to know next to nothing about how to sell them.

Like Orson Welles, Burnett tries something different every time he gets behind a camera, and some of his films slide off the map as a consequence. It doesn’t help that he’s an independent black filmmaker, as are some of his talented classmates from UCLA, such as Billy Woodbury and Larry Clark. (Woodbury’s Bless Their Little Hearts, from 1984, written and shot by Burnett, is nearly impossible to see, and Clark’s 1977 Passing Through, one of the best features about jazz I know, is even more scarce; the only time I was able to see it was in the 80s.) The 19 completed works credited to Burnett as a director on the Internet Movie Database don’t include The Final Insult (1997), a 55-minute digital video that I reviewed at some length in the Reader when it came out, and I wouldn’t be at all surprised if there were other omissions as well. Indeed, it’s been so difficult keeping abreast of his work that I once proposed to Film Comment (without success) that they run a periodic feature in their front pages called “Burnett Watch,” tracking his activities as a filmmaker, many of which we wouldn’t know about otherwise. The last time I saw him, at the Mar del Plata International Film Festival in Buenos Aires in March, I attended a master class with him devoted to an ambitious feature he’s been shooting in Africa for the past several years.

Most of my colleagues consider Killer of Sheep to be Burnett’s greatest film to date, but I’m not so sure. My own favorite, which appeared on my last all-time ten-best list in Sight & Sound, is When It Rains (1995), a 13-minute short made for French TV [see still below]. It has shown in Chicago more than once, but since it isn’t on DVD or VHS, it’s barely known. By the end of this year, when Milestone finally brings out its long-promised Burnett box set, this extraordinary film celebrating both jazz and community, made as a kind of respite and liberation after Burnett finished directing The Glass Shield for Miramax, will finally be available. But even when that happens, I don’t know whether Burnett’s second feature, My Brother’s Wedding (1983), will appear in the same set: Burnett completed it in a rush for a film festival and regards it as unfinished. [2010 update: happily, both versions are available in the same box set.]

I saw My Brother’s Wedding two or three times at various festivals in the mid-80s and didn’t think it seemed unfinished; in fact, I even remember preferring it to Killer of Sheep, in part because it has a more sustained and very affecting story line. My point, in any case, is that with a career as hard to keep tabs on as Burnett’s, we’re as far from being able to see, much less assess and rank, all his works, as we still are with Welles. So for the time being, let’s just say that Killer of Sheep — which is finally reaching us properly, the way it should have 30 years ago — is the best place to start.